eJournal: uffmm.org

ISSN 2567-6458, 14.January 2023 – 14.January 2023

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

CONTEXT

This is a special thought experiment with the chatbot chatGPT, as part of the uffmm.org blog.

CHAT No.4, 14.January 2023

‘*’ := Denotes the human Gerd, who is starting continues with questions and statements.

In this chat there was for the chatbot not the task to ‘complete’ a beginning text. It was rather a typical chat with ping-ponging statements of the human and statements of the machine.

Although this chat seems at a first glance quite ‘normal’ will it reveal in the follow-up reflections a lot of deep insights. Perhaps the results are quite different from the opinions which a reader of this chat will possibly have.

START OF CHAT

* At present, mankind is faced with the task of overcoming many problems of hitherto unknown magnitude in order to secure its own existence and that of the entire biosphere in the long term.

These problems include climate change, biodiversity loss, resource depletion and pollution. To address these issues, it is essential to adopt a holistic approach that focuses on the interconnectedness of all components of the environment. This means that solutions must be sought at the local, national and international level, and in all sectors of society, from government and industry to civil society. Solutions should also be both preventive and adaptive, and should focus on sustainable development and the protection of natural resources. This will require a paradigm shift in how we approach environmental management, and a commitment to long-term solutions that address the root causes of environmental degradation. Additionally, it is essential to invest in research and development to identify new and innovative solutions. Finally, it is important to ensure that such solutions are accessible and affordable to all people.

*What about communication of people?

In order to effectively tackle the problems of climate change, biodiversity loss, resource depletion and pollution, it is essential to engage people from all sectors of society in meaningful dialogue and collaboration. Effective communication of the challenges and potential solutions can help to build public understanding and support, while also helping to facilitate the sharing of resources, knowledge and expertise. Additionally, it is important to ensure that marginalized and vulnerable populations are not left behind in the quest for environmental sustainability. This means that we must create inclusive and equitable spaces for people to participate in the dialogue, and ensure that their voices are heard in the decision-making process.

*Which role play empirical theories in this process?

Empirical theories play an important role in understanding the complexities of environmental problems and developing effective solutions. By analyzing data and developing models, empirical theories help to identify the causes and effects of environmental degradation and to identify potential solutions. Such theories can also help to develop strategies and policies that are tailored to the local context and that take into consideration the needs of different stakeholders. Additionally, empirical theories can help to inform and shape public discourse around environmental issues, and to build public consensus and support for action.

*How I can get helpful forecasts out of empirical theories?

Empirical theories can provide helpful forecasts by analyzing data and developing predictive models. These predictive models can be used to identify potential future trends and to inform decision-making. For example, models can be used to forecast the impacts of climate change on ecosystems and species, or to predict the effects of a particular policy on resource depletion. Additionally, predictive models can be used to identify the most effective strategies for mitigating environmental degradation and to inform the development of long-term solutions.

*Which kinds of tools can help people to develop an empirical theory?

There are many tools that can help people to develop an empirical theory. These include statistical analysis software such as SPSS and R, as well as geographic information systems (GIS) such as ArcGIS and QGIS. Additionally, machine learning algorithms such as neural networks, decision trees and support vector machines can be used to identify patterns and relationships in large datasets. Finally, data visualization tools such as Tableau and Power BI can be used to make complex data more accessible and easier to interpret.

* Which role plays Philosophy of Science to explain what an empirical theory is?

Philosophy of Science plays an important role in understanding what an empirical theory is, and how it is developed. In particular, philosophy of science can help to explain the underlying assumptions and methodological approaches that are used to develop an empirical theory. It also helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different types of empirical theories, and to assess the validity of their conclusions. Additionally, philosophy of science can help to identify the underlying ethical considerations and implications of different empirical theories.

*Does empirical theory need any kind of logic?

Yes, empirical theory does need some kind of logic in order to be valid and reliable. This means that the assumptions and premises upon which an empirical theory is based must be logical and consistent. Additionally, the methodology used to develop the theory must be sound and rigorous, and the conclusions must be logically derived from the evidence. Finally, any decisions or actions taken based on an empirical theory should be based on a logical and well-reasoned argument.

*Is there only one kind of logic or do we have to consider different kinds?

There are many different kinds of logic that can be used to develop an empirical theory. These include inductive logic, which is used to draw general conclusions from specific observations; deductive logic, which is used to draw specific conclusions from general premises; and Bayesian logic, which combines inductive and deductive logic. Additionally, logic can be used to identify inconsistencies and contradictions in theories, and to identify the most logical and consistent theories and conclusions.

*What about Mathematics: do we need mathematics for an empirical theory?

Yes, mathematics plays an important role in the development of an empirical theory. This is because mathematical models and equations can help to identify patterns and relationships in data, as well as to make predictions about future trends. Additionally, mathematics can be used to estimate the magnitude of potential impacts, and to identify the most effective strategies for mitigating environmental degradation. Finally, mathematical models can be used to develop simulations that can help to inform decision-making.

*Beyond statistics: are there any kind of mathematical structures needed to model the data?

Yes, beyond basic statistics, more complex mathematical structures such as probability distributions, decision trees, and game theory can be used to model data and develop predictive models. Additionally, mathematical optimization techniques such as linear programming and dynamic programming can be used to identify the most efficient solutions to complex problems. Finally, simulation models such as agent-based models and system dynamics can be used to better understand the dynamics of complex systems and to inform decision-making.

*Today we experience in many societies a fragmentation of the public communication between the different groups. Which impact can this have on the trust of people in their society?

The fragmentation of public communication between different groups in society can have a significant impact on the trust of people in their society. When communication is fragmented, it can be difficult for people to understand each other and to build relationships of trust. Additionally, it can lead to a lack of understanding of different perspectives and ideologies, which can contribute to polarization and mistrust. Finally, it can lead to the creation of echo chambers, where the same ideas and opinions are repeated and reinforced, further contributing to mistrust and misunderstanding.

*What can people do to overcome a fragmented communication and the feeling of mistrust?

One of the most effective ways to overcome a fragmented communication and the feeling of mistrust is to engage in meaningful dialogue and collaboration. This means creating inclusive and equitable spaces for communication, and ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to participate in the dialogue. Additionally, it is important to listen to and respect different perspectives and ideologies, and to be open to learning from others. Finally, it is important to strive for common understanding and compromise, and to commit to long-term solutions that benefit all members of society.

*What can we do if the fragmented communication is partially induced by rivaling ethical values which are highly incompatible?

If fragmented communication is partially induced by rivaling ethical values which are highly incompatible, it is important to find common ground and create shared understanding. This can be done by engaging in meaningful dialogue and collaboration in order to identify areas of agreement and common goals. Additionally, it is important to identify and address the underlying causes of the disagreement, and to strive for compromise and mutual understanding. Finally, it is important to ensure that all voices are heard and respected, and to create equitable and inclusive spaces for communication.

*Can you distinguish different kinds of ethics?

Yes, there are many different kinds of ethics. These include deontological ethics, which focus on moral obligations and duties; consequentialist ethics, which focus on the consequences of actions; virtue ethics, which focus on the character of the individual; and utilitarian ethics, which focus on maximizing happiness and minimizing suffering. Additionally, there are many other theories and philosophies of ethics, such as environmental ethics, animal ethics, and feminist ethics.

*Does there exist some relationship between ethics and religion?

Yes, there is a relationship between ethics and religion. Many religions have ethical teachings and beliefs, and many people use their religion as a source of guidance for ethical decisions. Additionally, religious beliefs can often provide a moral foundation for ethical behavior, and many religions promote ethical values such as compassion and justice. Finally, religious teachings and ethical practices can often overlap, providing a shared understanding of morality and human behavior.

*This sounds good, but didn’t in the past not different kinds of religious belief also cause great harm to people?

Yes, different kinds of religious beliefs have in the past caused great harm to people. This is particularly true when religious beliefs are used to justify discrimination, violence, or oppression. Additionally, religious beliefs can be used to create a sense of superiority or to justify exclusion of certain groups of people. Ultimately, it is important to recognize the potential harms of religious beliefs and to strive for a culture of mutual understanding and respect.

*Does ethics have some relationship to the concept of truth?

Yes, ethics and the concept of truth have a relationship. In general, ethical standards dictate what is considered to be right and wrong, while the concept of truth is concerned with what is actually true. Thus, ethical standards are based on an understanding of what is true, and what is right and wrong is determined in part by an understanding of truth. Additionally, truth can be used to evaluate ethical decisions, as truth can be used to determine whether an action is just or unjust.

*Which role do emotions and feelings play to support a certain ethical position?

Emotions and feelings can play a significant role in supporting a certain ethical position. For example, feelings of empathy and compassion can lead to a desire for justice and fairness, while feelings of anger and indignation can lead to a desire for retribution and punishment. Additionally, emotions can be used to motivate people to take action in support of a certain ethical position, and can provide the courage and strength to do what is right. Finally, emotions can help to create a sense of shared understanding and solidarity, which can help to create more inclusive and equitable ethical standards.

*Does this mean that emotions and feelings are somehow part of a rational behavior of men?

Yes, emotions and feelings can be part of a rational behavior. Emotions can provide valuable insights and information about a situation, and can often be used to make ethical decisions. Additionally, emotions can help to motivate people to act in a certain way, and can help to create a sense of solidarity and shared understanding. Ultimately, emotions and feelings can be a valuable tool for making ethical decisions, and for understanding and evaluating the world around us.

*There are people which claim that a mystical experience is very important. Does this fit into the overall picture of rationality?

Yes, mystical experiences can fit into the overall picture of rationality. Mystical experiences are often characterized by a deep connection to the spiritual world, and can provide a sense of understanding and clarity. Additionally, mystical experiences can provide a source of insight and understanding, which can help to inform ethical decision making. Finally, mystical experiences can provide a source of comfort and peace, which can be an important part of a rational and ethical life.

*If we have a society with different groups of people, with different kinds of ethics, different kinds of emotions, even different kinds of mystical experience: how can these people live together in freedom?

In order for people with different kinds of ethics, emotions, and mystical experiences to live together in freedom, it is important to create an environment of respect and understanding. This means listening to and respecting different perspectives, striving for common understanding, and working together to find solutions that benefit everyone. Additionally, it is important to create equitable and inclusive spaces for dialogue and collaboration, and to ensure that all voices are heard and respected. Finally, it is important to strive for compromise and mutual understanding, and to commit to long-term solutions that benefit all members of society.

*This sounds good. But what about those societies where people are not allowed to communicate and act in freedom?

In societies where people are not allowed to communicate and act in freedom, it is important to advocate for change. This means speaking out against oppressive policies and systems, and working to create equitable and inclusive spaces for communication and action. Additionally, it is important to support and empower those who are oppressed, and to create platforms for dialogue and collaboration. Finally, it is important to strive for meaningful and lasting change, and to commit to long-term solutions that benefit all members of society.

*Committing to long-term solutions for the good of all: How could machines help humans to enable good solutions?

Machines can help humans to enable good solutions in a variety of ways. For example, machines can be used to analyze large amounts of data, allowing for more accurate and efficient decision making. Additionally, machines can be used to automate repetitive tasks, freeing up time for humans to focus on more complex problems. Finally, machines can be used to create simulations and models, allowing for better understanding of complex systems and a better understanding of how different solutions might impact a given situation.

*Such machines have to be developed and built. Who can do this?

Machines can be developed and built by a variety of people, including engineers, computer scientists, and software developers. Additionally, there are a number of companies and organizations that specialize in developing and building machines for specific tasks and applications. Finally, many universities and research institutions have teams of experts that are dedicated to researching and developing new machines and technologies.

*This sounds as if only a small group of specialists is involved. What about all the other people: How can they participate in those developments?

There are many ways that people who are not specialists can participate in machine development and building. For example, they can provide feedback and insight on the design and intended use of the machines. Additionally, they can help to identify potential ethical issues with the use of the machines, and provide suggestions for how to address these issues. Finally, they can participate in public debates and discussions about the use of machines, and can advocate for responsible and ethical usage of technology.

*Yes, in principle, that would be possible. But what about the reality: is there any company which really is looking for the demands of the society?

Yes, there are many companies that are actively looking for the demands of society when it comes to machine development and building. For example, many technology companies are actively engaging with the public to ensure that their products and services are ethical and responsible. Additionally, many companies are investing in research and development to create more equitable and inclusive machines and technologies. Finally, many companies are creating platforms for public discussion and debate to ensure that all voices are heard and respected.

*There is a big discussion about the impact of different digital platforms on the mind and emotions of young people, especially children. Why should the companies behind these platforms change their business models if they earn a lot of money with them?

Companies behind digital platforms should change their business models because they have a responsibility to protect the mental and emotional health of young people, especially children. This means creating platforms that are inclusive and equitable, and that prioritize safety, privacy, and well-being. Additionally, it means creating platforms that are free from discrimination, harassment, and bullying, and that provide users with the tools and resources they need to make informed decisions. Finally, it means creating platforms that are designed with the best interests of young people in mind, and that promote positive mental health and well-being.

*Let us switch to those platforms which offer different kinds of knowledge, especially Wikipedia. Is there some idea how to improve these knowledge platforms even more?

Yes, there are many ways to improve knowledge platforms such as Wikipedia. For example, these platforms can be made more accessible and user-friendly, with better navigation and search tools. Additionally, these platforms can be made more inclusive, with more diverse and representative content. Finally, these platforms can be made more interactive, with more opportunities for collaboration and dialogue. Additionally, these platforms can be made more reliable, with better quality control and fact-checking processes. OK, this thematizes mostly the properties of the interactions between user and platform. What about the kind of knowledge which is available.

*Can there be more knowledge content besides texts, images, audios and videos?

Yes, there are many other kinds of knowledge content that can be made available on knowledge platforms besides texts, images, audios, and videos. For example, knowledge platforms can incorporate interactive elements such as quizzes and simulations. Additionally, knowledge platforms can provide access to open data sets, allowing users to explore and analyze data. Finally, knowledge platforms can provide access to virtual reality environments, allowing users to experience and explore different topics in new and exciting ways.

*In which sense can knowledge platforms help people to understand better how the real world is functioning?

Knowledge platforms can help people to better understand how the real world is functioning by providing access to reliable and accurate information. Additionally, knowledge platforms can provide access to interactive elements such as simulations and quizzes, which can help to illustrate and explain complex topics. Finally, knowledge platforms can provide access to virtual reality environments, allowing users to explore and experience different topics in a more immersive and engaging way.

*Back to knowledge: does it make a difference to use algorithms or to use theories to explain the world?

Yes, algorithms and theories can be used to explain the world in different ways. Algorithms are used to process and analyze data, and can provide insights into how the world works. On the other hand, theories are used to explain the world in a more abstract and theoretical way, providing a more holistic understanding of complex topics. Ultimately, both algorithms and theories can be used to understand the world, and the most effective approach will depend on the context and the goal.

*Is it correct to say that an algorithm cannot be true or false, but a theory can?

Yes, it is correct to say that an algorithm cannot be true or false, whereas a theory can. This is because algorithms are used to process and analyze data, while theories are used to explain the world in a more abstract and theoretical way. Thus, algorithms cannot be said to be true or false, while theories can be evaluated based on how well they explain the world.

*There are people who deny that we can have a common understanding of what is meant by saying that a statement is true. What is your opinion about this?

My opinion is that it is possible to have a common understanding of what is meant by saying that a statement is true. This is because truth is a concept that is relative to the context and the individual, and the same statement can be considered true or false depending on how it is interpreted. Thus, by engaging in meaningful dialogue and collaboration, it is possible to reach a common understanding of the truth of a given statement. Ultimately, truth is a subjective concept, and it is important to recognize and respect different perspectives.

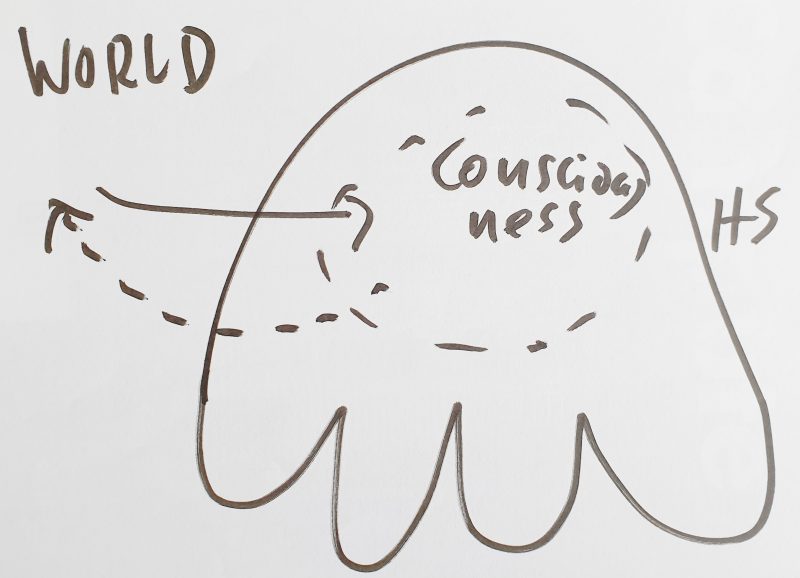

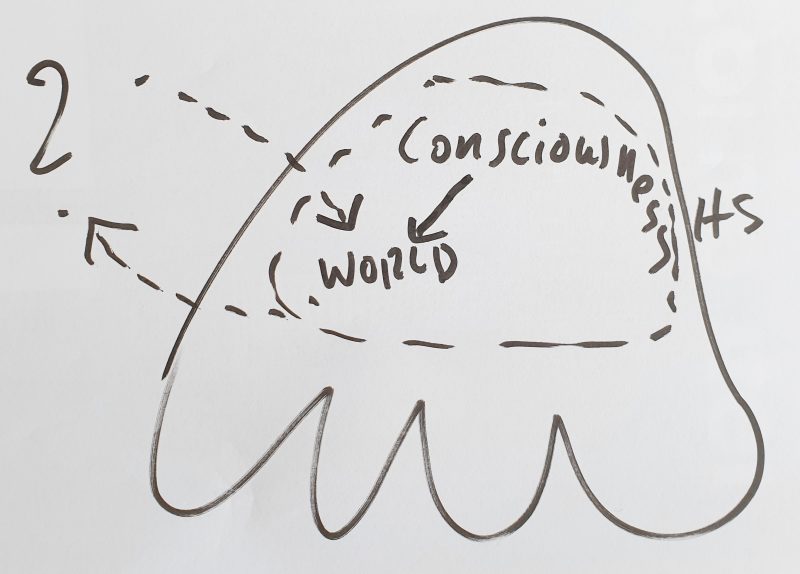

*This gives rise to the question how the real world is reflected in the subjective world of an individual person?

The real world is reflected in the subjective world of an individual person in a variety of ways. For example, an individual’s beliefs, values, and experiences can shape their perception of reality and the way they interpret the world around them. Additionally, an individual’s emotions and feelings can provide insights into their understanding of the world, and can be used to inform their decisions and actions. Finally, an individual’s relationships and interactions with others can provide insight into how they perceive the world, and can provide a source of understanding and shared meaning.

*OK, some people distinguish between being conscious about something and being unconscious. What does this mean for knowledge?

Being conscious about something and being unconscious can have implications for knowledge. Being conscious about something refers to an awareness of a concept or idea, while being unconscious refers to a lack of awareness. Thus, when it comes to knowledge, being conscious about something can mean having a better understanding and appreciation of a concept or idea, while being unconscious can mean having a limited or distorted understanding. Ultimately, it is important to strive for a conscious understanding of knowledge, and to be open to learning and exploring new ideas and perspectives.

*To which degree is the reality of a body being part of the consciousness of an individual person?

The reality of a body being part of the consciousness of an individual person can vary from person to person. For some, the physical body may be an important part of their consciousness, while for others it may not be as important or relevant. Ultimately, it is up to each individual to decide how much their physical body is part of their consciousness, and to what degree it should be taken into account when making decisions and navigating their lives.

*I did not mean the physical body as an object but all the billions of events inside a human body. How can the brain know about these and to which degree?

The brain can know about the billions of events inside the human body through a combination of sensory input and internal processing. For example, the senses can provide the brain with information about the environment, and the brain can use this information to make sense of the events taking place inside the body. Additionally, the brain can use its internal processing power to interpret and analyze the information it receives, allowing it to make decisions and take action. Ultimately, the degree to which the brain is aware of the events inside the body will depend on the individual and the context.

*There exist much more body cells as brain cells. Does this has some impact onto the self-knowledge of a person?

Yes, the fact that there are more body cells than brain cells can have an impact on a person’s self-knowledge. This is because the body is composed of many different systems and processes, and the brain is only able to process a limited amount of information at any given time. Thus, a person’s self-knowledge is limited by the ability of the brain to process and interpret the information it receives from the body. Additionally, it is important to recognize that the body and the brain are interconnected, and that changes in the body can have an impact on the brain, and vice versa.

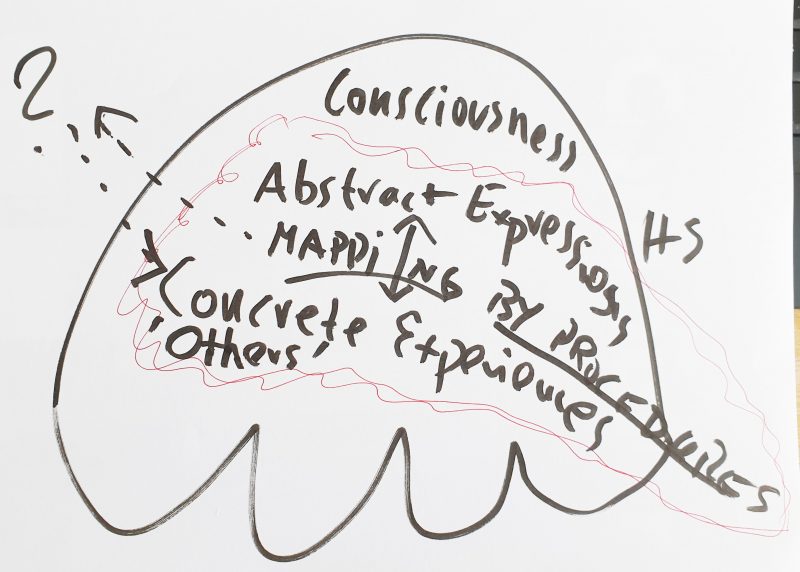

*Most parts of the human memory is in a moment not conscious, but it can become conscious. How does this work?

Most parts of the human memory are not conscious in the moment, but can become conscious through various processes. For example, memories can become conscious through recall, which is the process of retrieving memories from the unconscious mind. Additionally, memories can become conscious through association, which is the process of connecting memories to other memories or experiences. Finally, memories can become conscious through reflection and introspection, which is the process of analyzing and understanding memories and experiences.

*Many people are reporting that they are able to find solutions for complex problems without being conscious. How does this work?

Many people are able to find solutions for complex problems without being consciously aware of the process. This is because the brain is constantly processing information, even when we are not consciously aware of it. Thus, when faced with a complex problem, the brain can use its internal processing power to analyze the information and come up with a solution, even if the individual is not consciously aware of the process. Additionally, unconscious processes such as intuition and instinct can also be used to find solutions to complex problems.

*OK, this all sums up to the conclusion that human rationality is composed of emotions, spiritual experience as well as conscious as well as unconscious cognitive processes. Do I miss something important?

No, you have accurately summed up the components of human rationality. Additionally, human rationality is also composed of social and cultural influences, which can shape and inform our understanding of the world and our decisions. Additionally, human rationality is often impacted by our values and beliefs, which can provide a moral foundation for our behavior and decision making. Finally, human rationality is also impacted by our environment, which can provide a source of information and insight.

END OF CHAT

COMMENT

This chat looks at a first glance like a high level philosophical talk. There will probably be not too much people who are able to talk in such a way. And at a first glance it seems that the chatbot software called chatGPT can deal with this quite well. Thus should we give the software 5 points from 5? An answer will follow.

As the human counterpart in this chat with the chatbot I am inclined to say that even if it is rather clear how intrinsically limited the software still is (and probable will stay as such many more years by principal reasons) it gives some opportunity to train thinking a little bit like a tennis player can use ‘ball machines’ to train his reactions. The reason for this is the fact that while ‘thinking alone’ you have to ’emulate’ some counterpart by yourself (like a chess player has to think his own actions as well as the possible actions of the other player); this is possible but arduous and biased by your own ‘habits’ as well as by your ‘false ideas’ or by ‘missing ideas’ in your knowledge space. Furthermore everybody has lots of ‘unconscious’ preferences or blocking emotions which would not allow to think some ideas as an answer. But the machine intelligence — even if it is in several senses ‘limited’ — can probably ‘surround your knowledge wholes’, if the basis of the knowledge base is large enough and sufficient ‘diverse’.

And also the human part did not learn anything ‘new’ during this chat (sorry for this statement), and he could see many ‘knowledge gaps’ and to strong simplifications, the whole chat induced some ‘inspiring atmosphere’, more an emotional than purely ‘rational’. Apropos ‘rational’: that is a point which did surprise me really: as a kind of a summary it came out “that human rationality is composed of emotions, spiritual experience as well as conscious as well as unconscious cognitive processes.” This is clearly not what most philosophers today would say. But it follows from the ‘richness of the facts’ which came as a resonance out of this chat. Not that the chatbot would have given this summary in advance as an important characterization of rationality, but as a human counterpart I could summarize all this properties out of the different separated statements.

This last cognition can perhaps be a first ‘guide’ to a deeper understanding of human intelligence compared to machine intelligence: the machine intelligence needs humans, and humans can exploit machine intelligence on an ‘upper level’ … if we do ist 🙂