eJournal: uffmm.org

ISSN 2567-6458, 19.August 2022 – 25 August 2022, 14:26h

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

CONTEXT

This text is part of the subject COMMON SCIENCE as Sustainable Applied Empirical Theory, besides ENGINEERING, in a SOCIETY. It is a preliminary version, which is intended to become part of a book.

FORECASTING – PREDICTION: What?

optimal prediction

In the introduction of the main text it has been underlined that within a sustainable empirical theory it is not only necessary to widen the scope with a maximum of diversity, but at the same time it is also necessary to enable the capability for an optimal prediction about the ‘possible states of a possible future’.

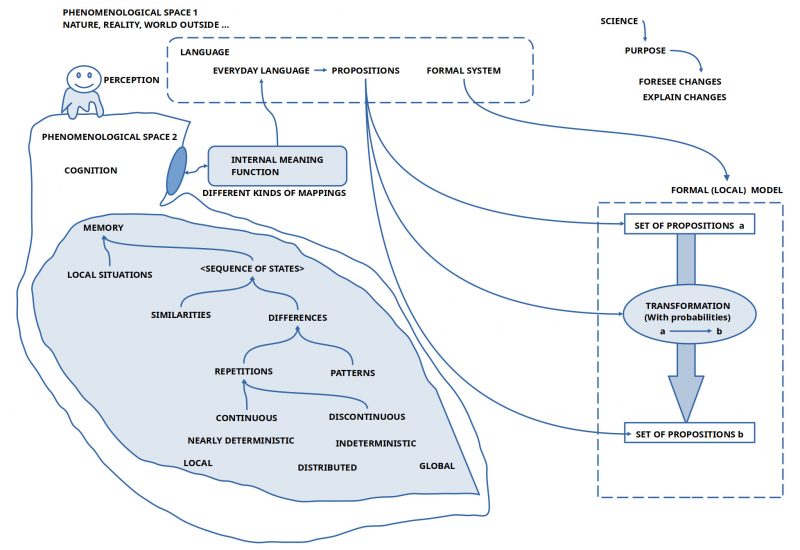

the meaning machinery

In the text after this introduction it has been outlined that between human actors the most powerful tool for the clarification of the given situation — the NOW — is the everyday language with a ‘built in’ potential in every human actor for infinite meanings. This individual internal meaning space as part of the individual cognitive structure is equipped with an ‘abstract – concrete’ meaning structure with the ability to distinguish between ‘true’ and ‘not true’, and furthermore equipped with the ability to ‘play around’ with meanings in a ‘new way’.

COORDINATION

Thus every human actor can generate within his cognitive dimension some states or situations accompanied with potential new processes leading to new states. To share this ‘internal meanings’ with other brains to ‘compare’ properties of the ‘own’ thinking with properties of the thinking of ‘others’ the only chance is to communicate with other human actors mediated by the shared everyday language. If this communication is successful it arises the possibility to ‘coordinate’ the own thinking about states and possible actions with others. A ‘joint undertaking’ is becoming possible.

shared thinking

To simplify the process of communication it is possible, that a human actor does not ‘wait’ until some point in the future to communicate the content of the thinking, but even ‘while the thinking process is going on’ a human actor can ‘translate his thinking’ in language expressions which ‘fit the processed meanings’ as good as possible. Doing this another human actor can observe the language activity, can try to ‘understand’, and can try to ‘respond’ to the observations with his language expressions. Such an ‘interplay’ of expressions in the context of multiple thinking processes can show directly either a ‘congruence’ or a ‘difference’. This can help each participant in the communication to clarify the own thinking. At the same time an exchange of language expressions associated with possible meanings inside the different brains can ‘stimulate’ different kinds of memory and thinking processes and through this the space of shared meanings can be ‘enlarged’.

phenomenal space 1 and 2

Human actors with their ability to construct meaning spaces and the ability to share parts of the meaning space by language communication are embedded with their bodies in a ‘body-external environment’ usual called ‘external world’ or ‘nature’ associated with the property to be ‘real’.

Equipped with a body with multiple different kinds of ‘sensors’ some of the environmental properties can stimulate these sensors which in turn send neuronal signals to the embedded brain. The first stage of the ‘processing of sensor signals’ is usually called ‘perception’. Perception is not a passive 1-to-1 mapping of signals into the brain but it is already a highly sophisticated processing where the ‘raw signals’ of the sensors — which already are doing some processing on their own — are ‘transformed’ into more complex signals which the human actor in its perception does perceive as ‘features’, ‘properties’, ‘figures’, ‘patterns’ etc. which usually are called ‘phenomena’. They all together are called ‘phenomenal space’. In a ‘naive thinking’ this phenomenal space is taken ‘as the external world directly’. During life a human actor can learn — this must not happen! –, that the ‘phenomenal space’ is a ‘derived space’ triggered by an ‘assumed outside world’ which ’causes’ by its properties the sensors to react in a certain way. But the ‘actual nature’ of the outside world is not really known. Let us call the unknown outside world of properties ‘phenomenal space 1’ and the derived phenomenal space inside the body-brain ‘phenomenal space 2’.

TIMELY ORDERING

Due to the availability of the phenomenal space 2 the different human actors can try to ‘explore’ the ‘unknown assumed real world’ based on the available phenomena.

If one takes a wider look to the working of the brain of a human actor one can detect that the processing of the brain of the phenomenal space is using additional mechanisms:

- The phenomenal space is organized in ‘time slices’ of a certain fixed duration. The ‘content’ of a time slice during the time window (t,t’) will be ‘overwritten’ during the next time slice (t’,t”) by those phenomena, which are then ‘actual’, which are then constituting the NOW. The phenomena from the time window before (t’,t”) can become ‘stored’ in some other parts of the brain usually called ‘memory’.

- The ‘storing’ of phenomena in parts of the brain called ‘memory’ happens in a highly sophisticated way enabling ‘abstract structures’ with an ‘interface’ for ‘concrete properties’ typical for the phenomenal space, and which can become associated with other ‘content’ of the memory.

- It is an astonishing ability of the memory to enable an ‘ordering’ of memory contents related to situations as having occurred ‘before’ or ‘after’ some other property. Therefore the ‘content of the memory’ can represent collections of ‘stored NOWs’, which can be ‘ordered’ in a ‘sequence of NOWs’, and thereby the ‘dimension of time’ appears as a ‘framing property’ of ‘remembered phenomena’.

- Based on this capability to organize remembered phenomena in ‘sequences of states’ representing a so-called ‘timely order’ the brain can ‘operate’ on such sequences in various ways. It can e.g. ‘compare’ two states in such a sequence whether these are ‘the same’ or whether they are ‘different’. A difference points to a ‘change’ in the phenomenal space. Longer sequences — even including changes — can perhaps show up as ‘repetitions’ compared to ‘earlier’ sequences. Such ‘repeating sequences’ can perhaps represent a ‘pattern’ pointing to some ‘hidden factors’ responsible for the pattern.

formal representations [1]

Based on a rather sophisticated internal processing structure every human actor has the capability to compose language descriptions which can ‘represent’ with the aid of sets of language expressions different kinds of local situations. Every expression can represent some ‘meaning’ which is encoded in every human actor in an individual manner. Such a language encoding can partially becoming ‘standardized’ by shared language learning in typical everyday living situations. To that extend as language encodings (the assumed meaning) is shared between different human actors they can use this common meaning space to communicate their experience.

Based on the built-in property of abstract knowledge to have an interface to ‘more concrete’ meanings, which finally can be related to ‘concrete perceptual phenomena’ available in the sensual perceptions, every human actor can ‘check’ whether an actual meaning seems to have an ‘actual correspondence’ to some properties in the ‘real environment’. If this phenomenal setting in the phenomenal space 2 with a correspondence to the sensual perceptions is encoded in a language expression E then usually it is told that the ‘meaning of E’ is true; otherwise not.

Because the perceptual interface to an assumed real world is common to all human actors they can ‘synchronize’ their perceptions by sharing the related encoded language expressions.

If a group of human actors sharing a real situation agrees about a ‘set of language expressions’ in the sens that each expression is assumed to be ‘true’, then one can assume, that every expression ‘represents’ some encoded meanings which are related to the shared empirical situation, and therefore the expressions represent ‘properties of the assumed real world’. Such kinds of ‘meaning constructions’ can be further ‘supported’ by the usage of ‘standardized procedures’ called ‘measurement procedures’.

Under this assumption one can infer, that a ‘change in the realm of real world properties’ has to be encoded in a ‘new language expression’ associated with the ‘new real world properties’ and has to be included in the set of expressions describing an actual situation. At the same time it can happen, that an expression of the actual set of expressions is becoming ‘outdated’ because the properties, this expression has encoded, are gone. Thus, the overall ‘dynamics of a set of expressions representing an actual set of real world properties’ can be realized as follows:

- Agree on a first set of expression to be a ‘true’ description of a given set of real world properties.

- After an agreed period of time one has to check whether (i) the encoded meaning of an expression is gone or (ii) whether a new real world property has appeared which seems to be ‘important’ but is not yet encoded in a language expression of the set. Depending from this check either (i) one has to delete those expressions which are no longer ‘true’ or (ii) one has to introduce new expressions for the new real world properties.

In a strictly ‘observational approach’ the human actors are only observing the course of events after some — regular or spontaneous –time span, making their observations (‘measurements’) and compare these observations with their last ‘true description’ of the actual situation. Following this pattern of behavior they can deduce from the series of true descriptions <D1, D2, …, Dn> for every pair of descriptions (Di,Di+1) a ‘difference description’ as a ‘rule’ in the following way: (i) IF x is a subset of expressions in Di+1, which are not yet members of the set of expressions in Di, THEN ‘add’ these expressions to the set of expressions in Di. (ii) IF y is a subset of expressions in Di, which are no more members of the set of expressions in Di+1, THEN ‘delete’ these expressions from the set of expressions in Di. (iii) Construct a ‘condition-set’ of expressions as subset of Di, which has to be fulfilled to apply (i) and (ii).

Doing this for every pair of descriptions then one is getting a set of ‘change rules’ X which can be used, to ‘generate’ — starting with the first description D0 — all the follow-up descriptions only by ‘applying a change rule Xi‘ to the last generated description.

This first purely observational approach works, but every change rule Xi in this set of change rules X can be very ‘singular’ pointing to a true singularity in the mathematical sense, because there is not ‘common rule’ to predict this singularity.

It would be desirable to ‘dig into possible hidden factors’ which are responsible for the observed changes but they would allow to ‘reduce the number’ of individual change rules of X. But for such a ‘rule-compression’ there exists from the outset no usable knowledge. Such a reduction will only be possible if a certain amount of research work will be done hopefully to discover the hidden factors.

All the change rules which could be found through such observational processes can in the future be re-used to explore possible outcomes for selected situations.

COMMENTS

[1] For the final format of this section I have got important suggestions from René Thom by reading the introduction of his book “Structural Stability and Morphogenesis: An Outline of a General Theory of Models” (1972, 1989). See my review post HERE : https://www.uffmm.org/2022/08/22/rene-thom-structural-stability-and-morphogenesis-an-outline-of-a-general-theory-of-models-original-french-edition-1972-updated-by-the-author-and-translated-into-english-by-d-h-fowler-1989/