eJournal: uffmm.org,

ISSN 2567-6458, 27.February 2019

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

Last change: 28.February 2019 (Several corrections)

CONTEXT

An overview to the enhanced AAI theory version 2 you can find here. In this post we talk about the special topic how to proceed in a bottom-up approach.

BOTTOM-UP: THE GENERAL BLUEPRINT

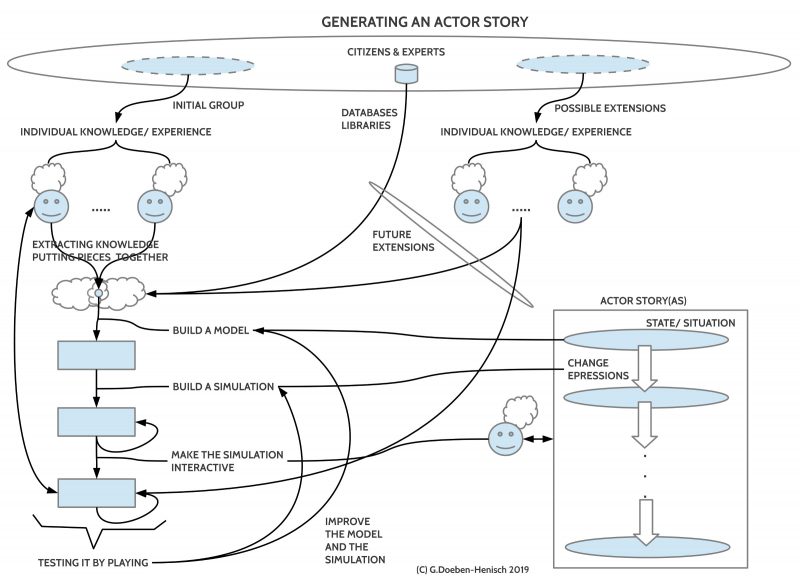

As the introductory figure shows it is assumed here that there is a collection of citizens and experts which offer their individual knowledge, experiences, and skills to ‘put them on the table’ challenged by a given problem P.

This knowledge is in the beginning not structured. The first step in the direction of an actor story (AS) is to analyze the different contributions in a way which shows distinguishable elements with properties and relations. Such a set of first ‘objects’ and ‘relations’ characterizes a set of facts which define a ‘situation’ or a ‘state’ as a collection of ‘facts’. Such a situation/ state can also be understood as a first simple ‘model‘ as response to a given problem. A model is as such ‘static‘; it describes what ‘is’ at a certain point of ‘time’.

In a next step the group has to identify possible ‘changes‘ which can be associated with at least one fact. There can be many possible changes which eventually need different durations to come into effect. These effects can happen as ‘exclusive alternatives’ or in ‘parallel’. Apply the possible changes to a situation generates ‘successors’ to the actual situation. A sequence of situations generated by applied changes is usually called a ‘simulation‘.

If one allows the interaction between real actors with a simulation by associating a real actor to one of the actors ‘inside the simulation’ one is turning the simulation into an ‘interactive simulation‘ which represents basically a ‘computer game‘ (short: ‘egame‘).

One can use interactive simulations e.g. to (i) learn about the dynamics of a model, to (ii) test the assumptions of a model, to (iii) test the knowledge and skills of the real actors.

Making new experiences with a simulation allows a continuous improvement of the model and its change rules.

Additionally one can include more citizens and experts into this process and one can use available knowledge from databases and libraries.

EPISTEMOLOGY OF CONCEPTS

As outlined in the preceding section about the blueprint of a bottom-up process there will be a heavy usage of concepts to describe state of affairs.

The literature about this topic in philosophy as well as many scientific disciplines is overwhelmingly and therefore this small text here can only be a ‘pointer’ into a complex topic. Nevertheless I will use exactly this pointer to explore this topic further.

While the literature is mainly dealing with more or less specific partial models, I am trying here to point out a very general framework which fits to a more genera philosophical — especially epistemological — view as well as gives respect to many results of scientific disciplines.

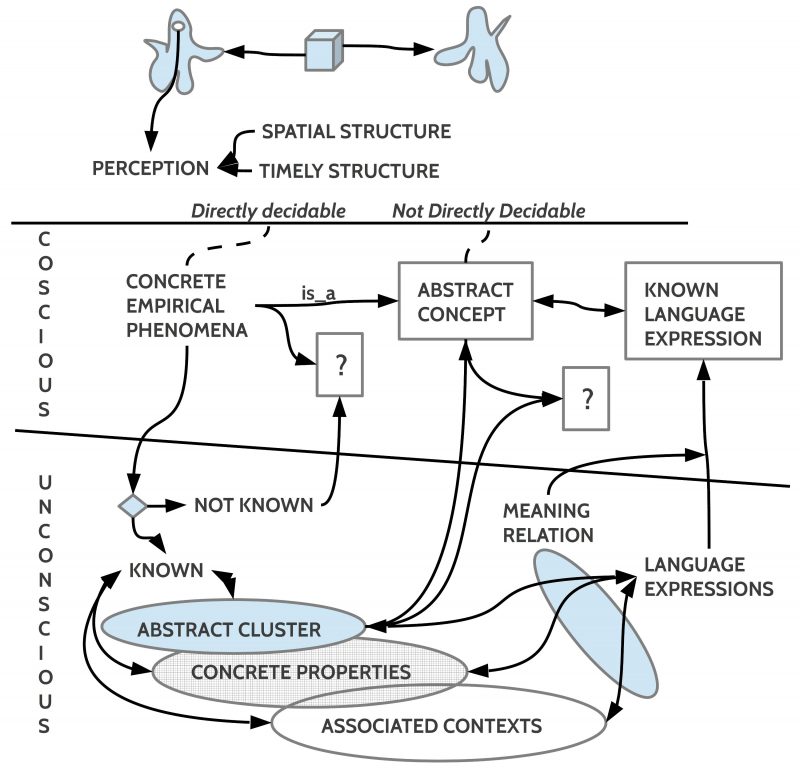

The main dimensions here are (i) the outside external empirical world, which connects via sensors to the (ii) internal body, especially the brain, which works largely ‘unconscious‘, and then (iii) the ‘conscious‘ part of he brain.

The most important relationship between the ‘conscious’ and the ‘unconscious’ part of the brain is the ability of the unconscious brain to transform automatically incoming concrete sens-experiences into more ‘abstract’ structures, which have at least three sub-dimensions: (i) different concrete material, (ii) a sub-set of extracted common properties, (iii) different sets of occurring contexts associated with the different subsets. This enables the brain to extract only a ‘few’ abstract structures (= abstract concepts) to deal with ‘many’ concrete events. Thus the abstract concept ‘chair’ can cover many different concrete chairs which have only a few properties in common. Additionally the chairs can occur in different ‘contexts’ associating them with different ‘relations’ which can specify possible different ‘usages’ of the concept ‘chair’.

Thus, if the actor perceives something which ‘matches’ some ‘known’ concept then the actor is not only conscious about the empirical concrete phenomenon but also simultaneously about the abstract concept which will automatically be activated. ‘Immediately’ the actor ‘knows’ that this empirical something is e.g. a ‘chair’. Concrete: this concrete something is matching an abstract concept ‘chair’ which can as such cover many other concrete things too which can be as concrete somethings partially different from another concrete something.

From this follows an interesting side effect: while an actor can easily decide, whether a concrete something is there (“it is the case, that” = “it is true”) or not (“it is not the case, that” = “it isnot true” = “it is false”), an actor can not directly decide whether an abstract concept like ‘chair’ as such is ‘true’ in the sense, that the concept ‘as a whole’ corresponds to concrete empirical occurrences. This depends from the fact that an abstract concept like ‘chair’ can match with a nearly infinite set of possible concrete somethings which are called ‘possible instances’ of the abstract concept. But a human actor can directly ‘check’ only a ‘few’ concrete somethings. Therefore the usage of abstract concepts like ‘chair’, ‘house’, ‘bottle’ etc. implies inherently an ‘open set’ of ‘possible’ concrete exemplars and therefor is the usage of such concepts necessarily a ‘hypothetical’ usage. Because we can ‘in principle’ check the real extensions of these abstract concepts in everyday life as long there is the ‘freedom’ to do such checks, we are losing the ‘truth’ of our concepts and thereby the basis for a realistic cooperation, if this ‘freedom of checking’ is not possible.

If some incoming perception is ‘not yet known’, because nothing given in the unconsciousness does ‘match’, it is in a basic sens ‘new’ and the brain will automatically generate a ‘new concept’.

THE DIMENSION OF MEANING

In Figure 2 one can find two other components: the ‘meaning relation’ which maps concepts into ‘language expression’.

Language expressions inside the brain correspond to a diversity of visual, auditory, tactile or other empirical event sequences, which are in use for communicative acts.

These language expressions are usually not ‘isolated structures’ but are embedded in relations which map the expression structures to conceptual structures including the different substantiations of the abstract concepts and the associated contexts. By these relations the expressions are attached to the conceptual structures which are called the ‘meaning‘ of the expressions and vice versa the expressions are called the ‘language articulation’ of the meaning structures.

As far as conceptual structures are related via meaning relations to language expressions then a perception can automatically cause the ‘activation’ of the associated language expressions, which in turn can be uttered in some way. But conceptual structures can exist (especially with children) without an available meaning relation.

When language expressions are used within a communicative act then their usage can activate in all participants of the communication the ‘learned’ concepts as their intended meanings. Heaving the meaning activated in someones ‘consciousness’ this is a real phenomenon for that actor. But from the occurrence of concepts alone does not automatically follow, that a concept is ‘backed up’ by some ‘real matter’ in the external world. Someone can utter that it is raining, in the hearer of this utterance the intended concepts can become activated, but in the outside external world no rain is happening. In this case one has to state that the utterance of the language expressions “Look, its raining” has no counterpart in the real world, therefore we call the utterance in this case ‘false‘ or ‘not true‘.

THE DIMENSION OF TIME

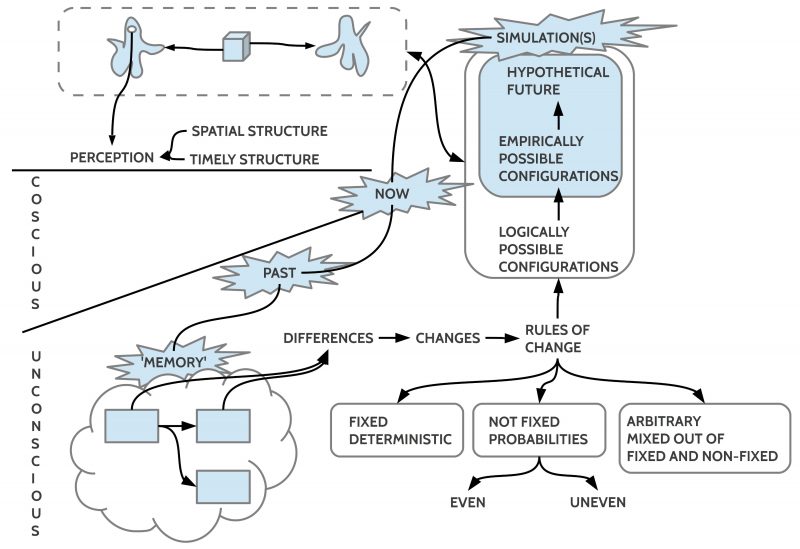

The preceding figure 2 of the conceptual space is not yet complete. There is another important dimension based on the ability of the unconscious brain to ‘store’ certain structures in a ‘timely order’ which enables an actor — under certain conditions ! — to decide whether a certain structure X occurred in the consciousness ‘before’ or ‘after’ or ‘at the same time’ as another structure Y.

Evidently the unconscious brain is able do exactly this: (i) it can arrange the different structures under certain conditions in a ‘timely order’; (ii) it can detect ‘differences‘ between timely succeeding structures; the brain (iii) can conceptualize these changes as ‘change concepts‘ (‘rules of change’), and it can can classify different kinds of change like ‘deterministic’, ‘non-deterministic’ with different kinds of probabilities, as well as ‘arbitrary’ as in the case of ‘free learning systems‘. Free learning systems are able to behave in a ‘deterministic-like manner’, but they can also change their patterns on account of internal learning and decision processes in nearly any direction.

Based on memories of conceptual structures and derived change concepts (rules of change) the unconscious brain is able to generate different kinds of ‘possible configurations’, whose quality is depending from the degree of dependencies within the ‘generating criteria’: (i) no special restrictions; (ii) empirical restrictions; (iii) empirical restrictions for ‘upcoming states’ (if all drinkable water would be consumed, then one cannot plan any further with drinkable water).