eJournal: uffmm.org, ISSN 2567-6458, Aug 17-18, 2021

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

SCOPE

In the uffmm review section the different papers and books are discussed from the point of view of the oksimo paradigm. [2] Here the author reads the book “Logic. The Theory Of Inquiry” by John Dewey, 1938. [1]

DISCUSSION after the PREFACE DEWEY 1938/9

Following the description and interpretation of Dewey’s preface the author takes here the time for a short discussion how one can describe the first idea of Dewey about the view of inquiry as a continuum, as a process with some outcome.

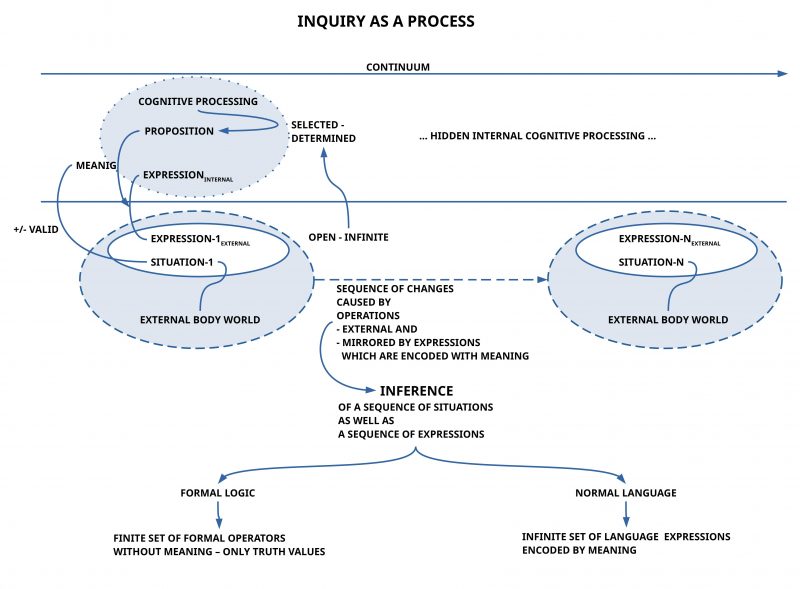

In the interpretation of Dewey the author takes the starting point with the view of Dewey of an inquiry as a continuous process.(cf. figure 1)

In his description of such an inquiry in the spirit of pragmatism Dewey claims that the process ends up in a situation which is caused by the preceding parts of the process. He calls the ‘end’ of such an inquiry process a consequence (or: consequences) which can be used as a test of the validity of the assumed propositions.

Validity of the proposition

Taking only the words of Dewey “validity of the … propositions” this can be interpreted in many ways. The author of this texts interprets these words with a conceptual framework based on the today knowledge about cognitive processing, which is also used in the oksimo paradigm.

In this modern framework of cognitive processing we know that one has at least to distinguish the dimension of the real world with real situations and as part of the real situation real objects, real actions (and more) on the one hand and inner states of an actor on the other hand.

As part of this overall scenario one has to distinguish at least the following main dimensions: (i) the overall observable real behavior of an actor and real expressions as part of the observable behavior, which can be classified (by learned knowledge) as expressions of some normal language, and (ii) the not-observable inner states of the actor reflecting in a special way the observable situation as such as well as the perceivable (by hearing, reading, …) expressions of the known language as part of the observable situation.

The main point here in the case of an actor of the life form homo sapiens is the fact that a homo sapiens actor is able to map the inner counterpart of the external expressions into the inner counterpart of the perceived real situation as part of a cognitive machinery (including memory) in a way that this internal mapping — here called meaning function — encodes part of the cognitive states into expressions (and vice versa).

Using this knowledge about the cognitive closure of expressions known as part of a learned language one can understand, why arbitrary aspects of the observable real situation can be encoded by the (built-in as well as learned ) meaning function into certain expressions in a way, that a hearer-reader of these expressions can decode these expressions (with his individual meaning function) to some extend into the inner cognitive states corresponding to the perceivable world.

In the light of this modern cognitive framework can a proposition be interpreted as part of the inner cognitive states corresponding either actually to some perceived real situation (then it is qualified as being valid) or not. And because the meaning function can encode such propositions with some expressions we can have external expressions as a real counterpart to such propositions.

Inquiry as a process

Thus inquiry understood by Dewey as a continuous process starts with some starting real situation which can be accompanied by appropriate (encoded) expressions of the selected language. During the course of inquiry the situation can change caused by actions which after some finite period of time lead to a final situation (‘final’ is not an absolute’ category here; it depends from the decision of the researchers what they think has to be understood as ‘final’).

While the possible process of inquiry in the beginning is quite unclear, open, undefined, turns the real process of actions (including speaking/ writing expressions) this undefined/ possibly infinite situation step by step into some real defined finite process by making decisions which enable selections of concrete actions/ things out of many options.

Test of the validity

Dewey speaks about the end of an inquiry process as a consequence which can be seen as a test of the validity of the propositions. If the ‘validity of a proposition’ is a qualification of the relation between a proposition as a cognitive counterpart of some perceivable real situation and this real situation then the wording ‘test of’ could be interpreted in the way that the reached situation by an inquiry process is in a sufficient agreement with an assumed proposition. But this would require that the researchers have in the beginning of their research have an idea of the intended/ wanted outcome. This sounds a bit strange: Why doing some inquiry if I already have an idea of the outcome?

This leads to the everyday life situation where we encounter permanently the following situations: (i) We know of situations which we qualify as being unsatisfying by some reasons (‘Gerd is hungry’, ‘Peter is tired’, ‘Ada is unhappy’, ‘John needs some money’, ‘Mary has a question’, ‘Bill looks for some new flat’, …); and (ii) some kind of visions/ goals, which we want to achieve. At the moment of having a vision/ goal within our inner cognitive states we can decide to achieve it through a real process of real actions. In some cases (being hungry) we probably have some options how to accomplish the goal by starting a series of concrete actions to get some food. And then the food is a consequence of the preceding process of searching and at the same time an answer to the triggering proposition. In other cases (‘being unhappy’ it can be difficult to find a good answer: what really is missing? What can I do? If Ada would decide to clarify her state it could happen that she tries a lot of options eventually lasting a long time (days, weeks, months, …). But nevertheless one day it can happen that she suddenly has the feeling, that she is no longer unhappy. In that case she can qualify the reached situation as a consequence of her preceding process of inquiry and indeed as an answer to the triggering proposition of being unhappy. In this case ‘feeling happy’ as an answer to ‘feeling unhappy’ has not been a clear expectation in the beginning, but a causing proposition which has lead Ada into a search process which finally produced a situation which enabled this new feeling of ‘being happy’ which — perhaps –is a quite ‘new’ feeling which nevertheless is understood by her as an ‘answer’.

Goals: defined and undefined

These simple examples point at the fact that homo sapiens actors can start inquiries either by somehow clearly defined goals or with ‘undefined goals‘ but caused by a ‘defined problem‘.

While the wording ‘undefined goal’ seems a little bit ‘fuzzy’ in the beginning, it is of great importance for the case of inquiry. This has to do with the concept of a possible future.

While the actual real world — and even those parts of it, which we have memorized somehow — is something we can perceive and where we can point at, is ‘future’ a non-object: we have strictly no chance to perceive directly any kind of future. Future is the radical unknown. What we can do — and in our everyday life we do it often — is, that we try to imagine by our past knowledge to get some hints out of the past for some patterns, regularities which can be used as ‘hints’ what perhaps can happen again with some probability as an upcoming situation because there exist some hidden mechanism in the real world which is causing a repetition (e.g. we have learned about phenomena which we call ‘gravity’ which we use as a cognitive tool to make some forecasts). But such learned patterns of the past do not explain everything and there is no absolute guarantee that these patterns will work ever. Moreover, we are living in a world which is maximal complex because of a multitude of patterns simultaneously at work, and there are many patterns (the behavior of biological systems) which are inherently non-linear, nondeterministic.

Thus doing inquiries into future states which are caused by defined problems where the answer is not yet known are radically different to inquiries with defined problems already accompanied with a clear goal. Although defined problems with defined goals can be quite difficult (e.g. searching for better material, better production processes etc. to get a better electrical battery for everyday usage) the case of an undefined goal is much more demanding. This case is the standard case for real research (as in the case of Ada: What makes her happy?).

COMMENTS

[1] John Dewey, Logic. The Theory Of Inquiry, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1938 (see: https://archive.org/details/JohnDeweyLogicTheTheoryOfInquiry with several formats; I am using the kindle (= mobi) format: https://archive.org/download/JohnDeweyLogicTheTheoryOfInquiry/%5BJohn_Dewey%5D_Logic_-_The_Theory_of_Inquiry.mobi . This is for the direct work with a text very convenient. Additionally I am using a free reader ‘foliate’ under ubuntu 20.04: https://github.com/johnfactotum/foliate/releases/). Additionally I am using a free reader ‘foliate’ under ubuntu 20.04: https://github.com/johnfactotum/foliate/releases/). The page numbers in the text of the review — like (p.13) — are the page numbers of the ebook as indicated in the ebook-reader foliate.(There exists no kindle-version for linux (although amazon couldn’t work without linux servers!))

[2] Gerd Doeben-Henisch, 2021, uffmm.org, THE OKSIMO PARADIGM

An Introduction (Version 2), https://www.uffmm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/oksimo-v1-part1-v2.pdf

Continuation

Part 3 (Last change: 20.Aug.2021)

MEDIA

Here is another talk completely unplugged about Dewey’s Logic. It’s focus is on a hypothetical conceptual framework for the wording of ‘valid propositions’ in the context of an inquiry.