Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Time: Jan 5, 2024 – Jan 8, 2024 (09:45 a.m. CET)

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

TRANSLATION: The following text is a translation from a German version into English. For the translation I am using the software deepL.com as well as chatGPT 4. The English version is a slightly revised version of the German text.

This blog entry will be completed today. However, it has laid the foundations for considerations that will be pursued further in a new blog entry.

CONTEXT

This text belongs to the topic Philosophy (of Science).

Introduction

Triggered by several reasons I started some investigation in the phenomenon of ‘propaganda’ to sharpen my understanding. My strategy was first to try to characterize the phenomenon of ‘general communication’ in order to find some ‘harder criteria’ that would allow to characterize the concept of ‘propaganda’ to stand out against this general background in a somewhat comprehensible way.

The realization of this goal then actually led to an ever more fundamental examination of our normal (human) communication, so that forms of propaganda become recognizable as ‘special cases’ of our communication. The worrying thing about this is that even so-called ‘normal communication’ contains numerous elements that can make it very difficult to recognize and pass on ‘truth’ (*). ‘Massive cases of propaganda’ therefore have their ‘home’ where we communicate with each other every day. So if we want to prevent propaganda, we have to start in everyday life.

(*) The concept of ‘truth’ is examined and explained in great detail in the following long text below. Unfortunately, I have not yet found a ‘short formula’ for it. In essence, it is about establishing a connection to ‘real’ events and processes in the world – including one’s own body – in such a way that they can, in principle, be understood and verified by others.

DICTATORIAL CONTEXT

However, it becomes difficult when there is enough political power that can set the social framework conditions in such a way that for the individual in everyday life – the citizen! – general communication is more or less prescribed – ‘dictated’. Then ‘truth’ becomes less and less or even non-existent. A society is then ‘programmed’ for its own downfall through the suppression of truth. ([3], [6]).

EVERYDAY LIFE AS A DICTATOR ?

The hour of narratives

But – and this is the far more dangerous form of ‘propaganda’ ! – even if there is not a nationwide apparatus of power that prescribes certain forms of ‘truth’, a mutilation or gross distortion of truth can still take place on a grand scale. Worldwide today, in the age of mass media, especially in the age of the internet, we can see that individuals, small groups, special organizations, political groups, entire religious communities, in fact all people and their social manifestations, follow a certain ‘narrative’ [*11] when they act.

Typical for acting according to a narrative is that those who do so individually believe that it is ‘their own decision’ and that their narrative is ‘true’, and that they are therefore ‘in the right’ when they act accordingly. This ‘feeling to be right’ can go as far as claiming the right to kill others because they ‘act wrongly’ in the light of their own ‘narrative’. We should therefore speak here of a ‘narrative truth’: Within the framework of the narrative, a picture of the world is drawn that ‘as a whole’ enables a perspective that ‘as such’ is ‘found to be good’ by the followers of the narrative, as ‘making sense’. Normally, the effect of a narrative, which is experienced as ‘meaningful’, is so great that the ‘truth content’ is no longer examined in detail.

RELIGIOUS NARRATIVES

This has existed at all times in the history of mankind. Narratives that appeared as ‘religious beliefs’ were particularly effective. It is therefore no coincidence that almost all governments of the last millennia have adopted religious beliefs as state doctrines; an essential component of religious beliefs is that they are ‘unprovable’, i.e. ‘incapable of truth’. This makes a religious narrative a wonderful tool in the hands of the powerful to motivate people to behave in certain ways without the threat of violence.

POPULAR NARRATIVES

In recent decades, however, we have experienced new, ‘modern forms’ of narratives that do not come across as religious narratives, but which nevertheless have a very similar effect: People perceive these narratives as ‘giving meaning’ in a world that is becoming increasingly confusing and therefore threatening for everyone today. Individual people, the citizens, also feel ‘politically helpless’, so that – even in a ‘democracy’ – they have the feeling that they cannot directly influence anything: the ‘people up there’ do what they want. In such a situation, ‘simplistic narratives’ are a blessing for the maltreated soul; you hear them and have the feeling: yes, that’s how it is; that’s exactly how I ‘feel’!

Such ‘popular narratives’, which enable ‘good feelings’, are gaining ever greater power. What they have in common with religious narratives is that the ‘followers’ of popular narratives no longer ask the ‘question of truth’; most of them are also not sufficiently ‘trained’ to be able to clarify the truth of a narrative at all. It is typical for supporters of narratives that they are generally hardly able to explain their own narrative to others. They typically send each other links to texts/videos that they find ‘good’ because these texts/videos somehow seem to support the popular narrative, and tend not to check the authors and sources because they are in the eyes of the followers such ‘decent people’, which always say exactly the ‘same thing’ as the ‘popular narrative’ dictates.

NARRATIVES ARE SEXY FOR POWER

If you now take into account that the ‘world of narratives’ is an extremely tempting offer for all those who have power over people or would like to gain power over people, then it should come as no surprise that many governments in this world, many other power groups, are doing just that today: they do not try to coerce people ‘directly’, but they ‘produce’ popular narratives or ‘monitor’ already existing popular narratives’ in order to gain power over the hearts and minds of more and more people via the detour of these narratives. Some speak here of ‘hybrid warfare’, others of ‘modern propaganda’, but ultimately, I guess, these terms miss the core of the problem.

THE NARRATIVE AS A BASIC CULTURAL PATTERN

The ‘irrational’ defends itself against the ‘rational’

The core of the problem is the way in which human communities have always organized their collective action, namely through narratives; we humans have no other option. However, such narratives – as the considerations further down in the text will show – are extremely susceptible to ‘falsity’, to a ‘distortion of the picture of the world’. In the context of the development of legal systems, approaches have been developed during at least the last 7000 years to ‘improve’ the abuse of power in a society by supporting truth-preserving mechanisms. Gradually, this has certainly helped, with all the deficits that still exist today. Additionally, about 500 years ago, a real revolution took place: humanity managed to find a format with the concept of a ‘verifiable narrative (empirical theory)’ that optimized the ‘preservation of truth’ and minimized the slide into untruth. This new concept of ‘verifiable truth’ has enabled great insights that before were beyond imagination .

The ‘aura of the scientific’ has meanwhile permeated almost all of human culture, almost! But we have to realize that although scientific thinking has comprehensively shaped the world of practicality through modern technologies, the way of scientific thinking has not overridden all other narratives. On the contrary, the ‘non-truth narratives’ have become so strong again that they are pushing back the ‘scientific’ in more and more areas of our world, patronizing it, forbidding it, eradicating it. The ‘irrationality’ of religious and popular narratives is stronger than ever before. ‘Irrational narratives’ are for many so appealing because they spare the individual from having to ‘think for themselves’. Real thinking is exhausting, unpopular, annoying and hinders the dream of a simple solution.

THE CENTRAL PROBLEM OF HUMANITY

Against this backdrop, the widespread inability of people to recognize and overcome ‘irrational narratives’ appears to be the central problem facing humanity in mastering the current global challenges. Before we need more technology (we certainly do), we need more people who are able and willing to think more and better, and who are also able to solve ‘real problems’ together with others. Real problems can be recognized by the fact that they are largely ‘new’, that there are no ‘simple off-the-shelf’ solutions for them, that you really have to ‘struggle’ together for possible insights; in principle, the ‘old’ is not enough to recognize and implement the ‘true new’, and the future is precisely the space with the greatest amount of ‘unknown’, with lots of ‘genuinely new’ things.

The following text examines this view in detail.

MAIN TEXT FOR EXPLANATION

MODERN PROPAGANDA ?

As mentioned in the introduction the trigger for me to write this text was the confrontation with a popular book which appeared to me as a piece of ‘propaganda’. When I considered to describe my opinion with own words I detected that I had some difficulties: what is the difference between ‘propaganda’ and ‘everyday communication’? This forced me to think a little bit more about the ingredients of ‘everyday communication’ and where and why a ‘communication’ is ‘different’ to our ‘everyday communication’. As usual in the beginning of some discussion I took a first look to the various entries in Wikipedia (German and English). The entry in the English Wikipedia on ‘Propaganda [1b] attempts a very similar strategy to look to ‘normal communication’ and compared to this having a look to the phenomenon of ‘propaganda’, albeit with not quite sharp contours. However, it provides a broad overview of various forms of communication, including those forms that are ‘special’ (‘biased’), i.e. do not reflect the content to be communicated in the way that one would reproduce it according to ‘objective, verifiable criteria’.[*0] However, the variety of examples suggests that it is not easy to distinguish between ‘special’ and ‘normal’ communication: What then are these ‘objective verifiable criteria’? Who defines them?

Assuming for a moment that it is clear what these ‘objectively verifiable criteria’ are, one can tentatively attempt a working definition for the general (normal?) case of communication as a starting point:

Working Definition:

The general case of communication could be tentatively described as a simple attempt by one person – let’s call them the ‘author’ – to ‘bring something to the attention’ of another person – let’s call them the ‘interlocutor’. We tentatively call what is to be brought to their attention ‘the message’. We know from everyday life that an author can have numerous ‘characteristics’ that can affect the content of his message.

Here is a short list of properties that characterize the author’s situation in a communication. Then corresponding properties for the interlocutor.

The Author:

- The available knowledge of the author — both conscious and unconscious — determines the kind of message the author can create.

- His ability to discern truth determines whether and to what extent he can differentiate what in his message is verifiable in the real world — present or past — as ‘accurate’ or ‘true’.

- His linguistic ability determines whether and how much of his available knowledge can be communicated linguistically.

- The world of emotions decides whether he wants to communicate anything at all, for example, when, how, to whom, how intensely, how conspicuously, etc.

- The social context can affect whether he holds a certain social role, which dictates when he can and should communicate what, how, and with whom.

- The real conditions of communication determine whether a suitable ‘medium of communication’ is available (spoken sound, writing, sound, film, etc.) and whether and how it is accessible to potential interlocutors.

- The author’s physical constitution decides how far and to what extent he can communicate at all.

The Interlocutor:

- In general, the characteristics that apply to the author also apply to the interlocutor. However, some points can be particularly emphasized for the role of the interlocutor:

- The available knowledge of the interlocutor determines which aspects of the author’s message can be understood at all.

- The ability of the interlocutor to discern truth determines whether and to what extent he can also differentiate what in the conveyed message is verifiable as ‘accurate’ or ‘true’.

- The linguistic ability of the interlocutor affects whether and how much of the message he can absorb purely linguistically.

- Emotions decide whether the interlocutor wants to take in anything at all, for example, when, how, how much, with what inner attitude, etc.

- The social context can also affect whether the interlocutor holds a certain social role, which dictates when he can and should communicate what, how, and with whom.

- Furthermore, it can be important whether the communication medium is so familiar to the interlocutor that he can use it sufficiently well.

- The physical constitution of the interlocutor can also determine how far and to what extent the interlocutor can communicate at all.

Even this small selection of factors shows how diverse the situations can be in which ‘normal communication’ can take on a ‘special character’ due to the ‘effect of different circumstances’. For example, an actually ‘harmless greeting’ can lead to a social problem with many different consequences in certain roles. A seemingly ‘normal report’ can become a problem because the contact person misunderstands the message purely linguistically. A ‘factual report’ can have an emotional impact on the interlocutor due to the way it is presented, which can lead to them enthusiastically accepting the message or – on the contrary – vehemently rejecting it. Or, if the author has a tangible interest in persuading the interlocutor to behave in a certain way, this can lead to a certain situation not being presented in a ‘purely factual’ way, but rather to many aspects being communicated that seem suitable to the author to persuade the interlocutor to perceive the situation in a certain way and to adopt it accordingly. These ‘additional’ aspects can refer to many real circumstances of the communication situation beyond the pure message.

Types of communication …

Given this potential ‘diversity’, the question arises as to whether it will even be possible to define something like normal communication?

In order to be able to answer this question meaningfully, one should have a kind of ‘overview’ of all possible combinations of the properties of author (1-7) and interlocutor (1-8) and one should also have to be able to evaluate each of these possible combinations with a view to ‘normality’.

It should be noted that the two lists of properties author (1-7) and interlocutor (1-8) have a certain ‘arbitrariness’ attached to them: you can build the lists as they have been constructed here, but you don’t have to.

This is related to the general way in which we humans think: on one hand, we have ‘individual events that happen’ — or that we can ‘remember’ —, and on the other hand, we can ‘set’ ‘arbitrary relationships’ between ‘any individual events’ in our thinking. In science, this is called ‘hypothesis formation’. Whether or not such formation of hypotheses is undertaken, and which ones, is not standardized anywhere. Events as such do not enforce any particular hypothesis formations. Whether they are ‘sensible’ or not is determined solely in the later course of their ‘practical use’. One could even say that such hypothesis formation is a rudimentary form of ‘ethics’: the moment one adopts a hypothesis regarding a certain relationship between events, one minimally considers it ‘important’, otherwise, one would not undertake this hypothesis formation.

In this respect, it can be said that ‘everyday life’ is the primary place for possible working hypotheses and possible ‘minimum values’.

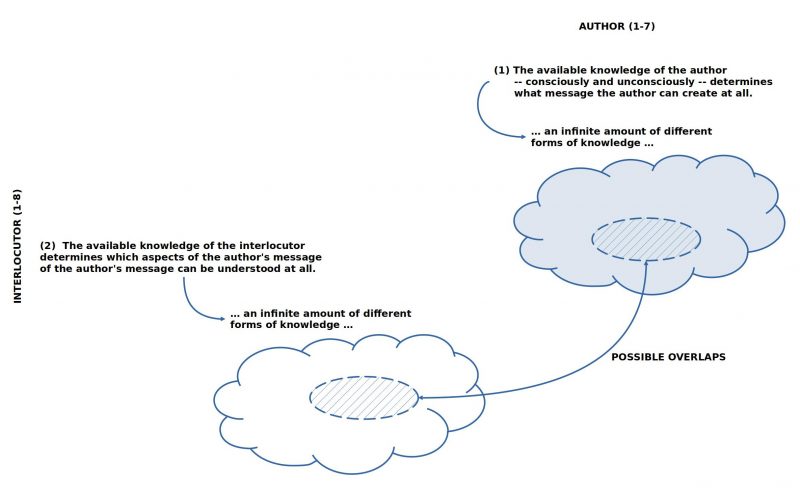

The following diagram demonstrates a possible arrangement of the characteristics of the author and the interlocutor:

FIGURE : Overview of the possible overlaps of knowledge between the author and the interlocutor, if everyone can have any knowledge at its disposal.

What is easy to recognize is the fact that an author can naturally have a constellation of knowledge that draws on an almost ‘infinite number of possibilities’. The same applies to the interlocutor. In purely abstract terms, the number of possible combinations is ‘virtually infinite’ due to the assumptions about the properties Author 1 and Interlocutor 2, which ultimately makes the question of ‘normality’ at the abstract level undecidable.

However, since both authors and interlocutors are not spherical beings from some abstract angle of possibilities, but are usually ‘concrete people’ with a ‘concrete history’ in a ‘concrete life-world’ at a ‘specific historical time’, the quasi-infinite abstract space of possibilities is narrowed down to a finite, manageable set of concretes. Yet, even these can still be considerably large when related to two specific individuals. Which person, with their life experience from which area, should now be taken as the ‘norm’ for ‘normal communication’?

It seems more likely that individual people are somehow ‘typified’, for example, by age and learning history, although a ‘learning history’ may not provide a clear picture either. Graduates from the same school can — as we know — possess very different knowledge afterwards, even though commonalities may be ‘minimally typical’.

Overall, the approach based on the characteristics of the author and the interlocutor does not seem to provide really clear criteria for a norm, even though a specification such as ‘the humanistic high school in Hadamar (a small German town) 1960 – 1968’ would suggest rudimentary commonalities.

One could now try to include the further characteristics of Author 2-7 and Interlocutor 3-8 in the considerations, but the ‘construction of normal communication’ seems to lead more and more into an unclear space of possibilities based on the assumptions of Author 1 and Interlocutor 2.

What does this mean for the typification of communication as ‘propaganda’? Isn’t ultimately every communication also a form of propaganda, or is there a possibility to sufficiently accurately characterize the form of ‘propaganda’, although it does not seem possible to find a standard for ‘normal communication’? … or will a better characterization of ‘propaganda’ indirectly provide clues for ‘non-propaganda’?

TRUTH and MEANING: Language as Key

The spontaneous attempt to clarify the meaning of the term ‘propaganda’ to the extent that one gets a few constructive criteria for being able to characterize certain forms of communication as ‘propaganda’ or not, gets into ever ‘deeper waters’. Are there now ‘objective verifiable criteria’ that one can work with, or not? And: Who determines them?

Let us temporarily stick to working hypothesis 1, that we are dealing with an author who articulates a message for an interlocutor, and let us expand this working hypothesis by the following addition 1: such communication always takes place in a social context. This means that the perception and knowledge of the individual actors (author, interlocutor) can continuously interact with this social context or ‘automatically interacts’ with it. The latter is because we humans are built in such a way that our body with its brain just does this, without ‘us’ having to make ‘conscious decisions’ for it.[*1]

For this section, I would like to extend the previous working hypothesis 1 together with supplement 1 by a further working hypothesis 2 (localization of language) [*4]:

- Every medium (language, sound, image, etc.) can contain a ‘potential meaning’.

- When creating the media event, the ‘author’ may attempt to ‘connect’ possible ‘contents’ that are to be ‘conveyed’ by him with the medium (‘putting into words/sound/image’, ‘encoding’, etc.). This ‘assignment’ of meaning occurs both ‘unconsciously/automatically’ and ‘(partially) consciously’.

- In perceiving the media event, the ‘interlocutor’ may try to assign a ‘possible meaning’ to this perceived event. This ‘assignment’ of meaning also happens both ‘unconsciously/automatically’ and ‘(partially) consciously’.

- The assignment of meaning requires both the author and the interlocutor to have undergone ‘learning processes’ (usually years, many years) that have made it possible to link certain ‘events of the external world’ as well as ‘internal states’ with certain media events.

- The ‘learning of meaning relationships’ always takes place in social contexts, as a media structure meant to ‘convey meaning’ between people belongs to everyone involved in the communication process.

- Those medial elements that are actually used for the ‘exchange of meanings’ all together form what is called a ‘language’: the ‘medial elements themselves’ form the ‘surface structure’ of the language, its ‘sign dimension’, and the ‘inner states’ in each ‘actor’ involved, form the ‘individual-subjective space of possible meanings’. This inner subjective space comprises two components: (i) the internally available elements as potential meaning content and (ii) a dynamic ‘meaning relationship’ that ‘links’ perceived elements of the surface structure and the potential meaning content.

To answer the guiding question of whether one can “characterize certain forms of communication as ‘propaganda’ or not,” one needs ‘objective, verifiable criteria’ on the basis of which a statement can be formulated. This question can be used to ask back whether there are ‘objective criteria’ in ‘normal everyday dialogue’ that we can use in everyday life to collectively decide whether a ‘claimed fact’ is ‘true’ or not; in this context, the word ‘true’ is also used. Can this be defined a bit more precisely?

For this I propose an additional working hypotheses 3:

- At least two actors can agree that a certain meaning, associated with the media construct, exists as a sensibly perceivable fact in such a way that they can agree that the ‘claimed fact’ is indeed present. Such a specific occurrence should be called ‘true 1’ or ‘Truth 1.’ A ‘specific occurrence’ can change at any time and quickly due to the dynamics of the real world (including the actors themselves), for example: the rain stops, the coffee cup is empty, the car from before is gone, the empty sidewalk is occupied by a group of people, etc.

- At least two actors can agree that a certain meaning, associated with the media construct, is currently not present as a real fact. Referring to the current situation of ‘non-occurrence,’ one would say that the statement is ‘false 1’; the claimed fact does not actually exist contrary to the claim.

- At least two actors can agree that a certain meaning, associated with the media construct, is currently not present, but based on previous experience, it is ‘quite likely’ to occur in a ‘possible future situation.’ This aspect shall be called ‘potentially true’ or ‘true 2’ or ‘Truth 2.’ Should the fact then ‘actually occur’ at some point in the future, Truth 2 would transform into Truth 1.

- At least two actors can agree that a certain meaning associated with the media construct does not currently exist and that, based on previous experience, it is ‘fairly certain that it is unclear’ whether the intended fact could actually occur in a ‘possible future situation’. This aspect should be called ‘speculative true’ or ‘true 3’ or ‘truth 3’. Should the situation then ‘actually occur’ at some point, truth 3 would change into truth 1.

- At least two actors can agree that a certain meaning associated with the medial construct does not currently exist, and on the basis of previous experience ‘it is fairly certain’ that the intended fact could never occur in a ‘possible future situation’. This aspect should be called ‘speculative false’ or ‘false 2’.

A closer look at these 5 assumptions of working hypothesis 3 reveals that there are two ‘poles’ in all these distinctions, which stand in certain relationships to each other: on the one hand, there are real facts as poles, which are ‘currently perceived or not perceived by all participants’ and, on the other hand, there is a ‘known meaning’ in the minds of the participants, which can or cannot be related to a current fact. This results in the following distribution of values:

| REAL FACTs | Relationship to Meaning | |

| Given | 1 | Fits (true 1) |

| Given | 2 | Doesn’t fit (false 1) |

| Not given | 3 | Assumed, that it will fit in the future (true 2) |

| Not given | 4 | Unclear, whether it would fit in the future (true 3) |

| Not given | 5 | Assumed, that it would not fit in the future (false 2) |

In this — still somewhat rough — scheme, ‘the meaning of thoughts’ can be qualified in relation to something currently present as ‘fitting’ or ‘not fitting’, or in the absence of something real as ‘might fit’ or ‘unclear whether it can fit’ or ‘certain that it cannot fit’.

However, it is important to note that these qualifications are ‘assessments’ made by the actors based on their ‘own knowledge’. As we know, such an assessment is always prone to error! In addition to errors in perception [*5], there can be errors in one’s own knowledge [*6]. So contrary to the belief of an actor, ‘true 1’ might actually be ‘false 1’ or vice versa, ‘true 2’ could be ‘false 2’ and vice versa.

From all this, it follows that a ‘clear qualification’ of truth and falsehood is ultimately always error-prone. For a community of people who think ‘positively’, this is not a problem: they are aware of this situation and they strive to keep their ‘natural susceptibility to error’ as small as possible through conscious methodical procedures [*7]. People who — for various reasons — tend to think negatively, feel motivated in this situation to see only errors or even malice everywhere. They find it difficult to deal with their ‘natural error-proneness’ in a positive and constructive manner.

TRUTH and MEANING : Process of Processes

In the previous section, the various terms (‘true1,2’, ‘false 1,2’, ‘true 3’) are still rather disconnected and are not yet really located in a tangible context. This will be attempted here with the help of working hypothesis 4 (sketch of a process space).

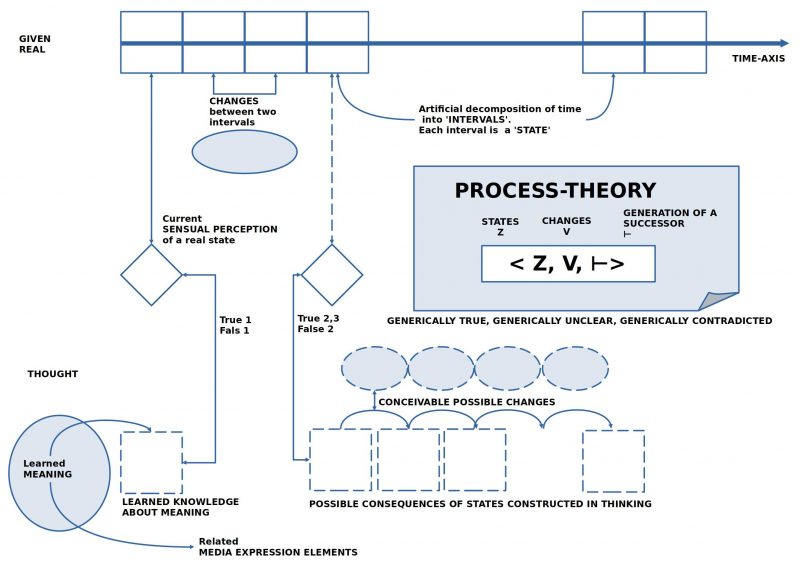

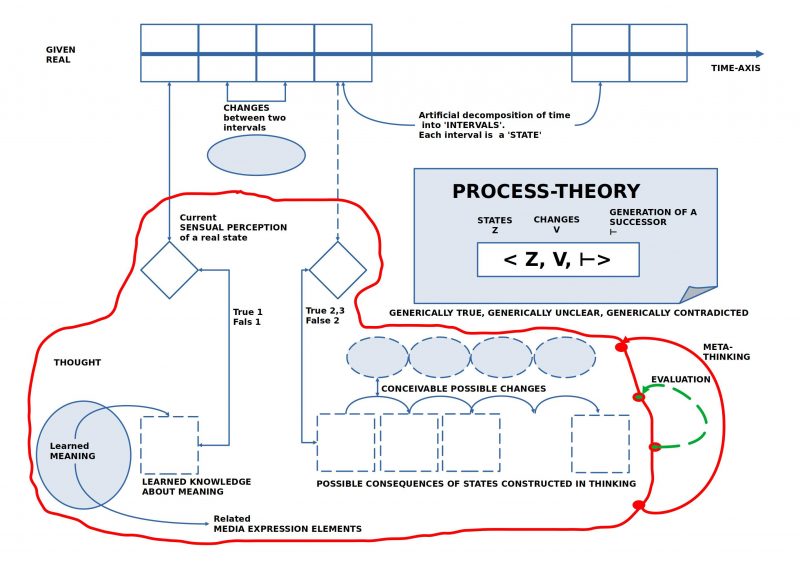

FIGURE 1 Process : The process space in the real world and in thinking, including possible interactions

The basic elements of working hypothesis 4 can be characterized as follows:

- There is the real world with its continuous changes, and within an actor which includes a virtual space for processes with elements such as perceptions, memories, and imagined concepts.

- The link between real space and virtual space occurs through perceptual achievements that represent specific properties of the real world for the virtual space, in such a way that ‘perceived contents’ and ‘imagined contents’ are distinguishable. In this way, a ‘mental comparison’ of perceived and imagined is possible.

- Changes in the real world do not show up explicitly but are manifested only indirectly through the perceivable changes they cause.

- It is the task of ‘cognitive reconstruction’ to ‘identify’ changes and to describe them linguistically in such a way that it is comprehensible, based on which properties of a given state, a possible subsequent state can arise.

- In addition to distinguishing between ‘states’ and ‘changes’ between states, it must also be clarified how a given description of change is ‘applied’ to a given state in such a way that a ‘subsequent state’ arises. This is called here ‘successor generation rule’ (symbolically: ⊢). An expression like Z ⊢V Z’ would then mean that using the successor generation rule ⊢ and employing the change rule V, one can generate the subsequent state Z’ from the state Z. However, more than one change rule V can be used, for example, ⊢{V1, V2, …, Vn} with the change rules V1, …, Vn.

- When formulating change rules, errors can always occur. If certain change rules have proven successful in the past in derivations, one would tend to assume for the ‘thought subsequent state’ that it will probably also occur in reality. In this case, we would be dealing with the situation ‘true 2’. If a change rule is new and there are no experiences with it yet, we would be dealing with the ‘true 3’ case for the thought subsequent state. If a certain change rule has failed repeatedly in the past, then the case ‘false 2’ might apply.

- The outlined process model also shows that the previous cases (1-5 in the table) only ever describe partial aspects. Suppose a group of actors manages to formulate a rudimentary process theory with many states and many change rules, including a successor generation instruction. In that case, it is naturally of interest how the ‘theory as a whole’ ‘proves itself’. This means that every ‘mental construction’ of a sequence of possible states according to the applied change rules under the assumption of the process theory must ‘prove itself’ in all cases of application for the theory to be said to be ‘generically true’. For example, while the case ‘true 1’ refers to only a single state, the case ‘generically true’ refers to ‘very many’ states, as many until an ‘end state’ is reached, which is supposed to count as a ‘target state’. The case ‘generically contradicted’ is supposed to occur when there is at least one sequence of generated states that keeps generating an end state that is false 1. As long as a process theory has not yet been confirmed as true 1 for an end state in all possible cases, there remains a ‘remainder of cases’ that are unclear. Then a process theory would be called ‘generically unclear’, although it may be considered ‘generically true’ for the set of cases successfully tested so far.

FIGURE 2 Process : The individual extended process space with an indication of the dimension ‘META-THINKING’ and ‘EVALUATION’.

If someone finds the first figure of the process room already quite ‘challenging’, they he will certainly ‘break into a sweat’ with this second figure of the ‘expanded process room’.

Everyone can check for himself that we humans have the ability — regardless of what we are thinking — to turn our thinking at any time back onto our own thinking shortly before, a kind of ‘thinking about thinking’. This opens up an ‘additional level of thinking’ – here called the ‘meta-level’ – on which we thinkers ‘thematize’ everything that is noticeable and important to us in the preceding thinking. [*8] In addition to ‘thinking about thinking’, we also have the ability to ‘evaluate’ what we perceive and think. These ‘evaluations’ are fueled by our ’emotions’ [*9] and ‘learned preferences’. This enables us to ‘learn’ with the help of our emotions and learned preferences: If we perform certain actions and suffer ‘pain’, we will likely avoid these actions next time. If we go to restaurant X to eat because someone ‘recommended’ it to us, and the food and/or service were really bad, then we will likely not consider this suggestion in the future. Therefore, our thinking (and our knowledge) can ‘make possibilities visible’, but it is the emotions that comment on what happens to be ‘good’ or ‘bad’ when implementing knowledge. But beware, emotions can also be mistaken, and massively so.[*10]

TRUTH AND MEANING – As a collective achievement

The previous considerations on the topic of ‘truth and meaning’ in the context of individual processes have outlined that and how ‘language’ plays a central role in enabling meaning and, based on this, truth. Furthermore, it was also outlined that and how truth and meaning must be placed in a dynamic context, in a ‘process model’, as it takes place in an individual in close interaction with the environment. This process model includes the dimension of ‘thinking’ (also ‘knowledge’) as well as the dimension of ‘evaluations’ (emotions, preferences); within thinking there are potentially many ‘levels of consideration’ that can relate to each other (of course they can also take place ‘in parallel’ without direct contact with each other (the unconnected parallelism is the less interesting case, however).

As fascinating as the dynamic emotional-cognitive structure within an individual actor can be, the ‘true power’ of explicit thinking only becomes apparent when different people begin to coordinate their actions by means of communication. When individual action is transformed into collective action in this way, a dimension of ‘society’ becomes visible, which in a way makes the ‘individual actors’ ‘forget’, because the ‘overall performance’ of the ‘collectively connected individuals’ can be dimensions more complex and sustainable than any one individual could ever realize. While a single person can make a contribution in their individual lifetime at most, collectively connected people can accomplish achievements that span many generations.

On the other hand, we know from history that collective achievements do not automatically have to bring about ‘only good’; the well-known history of oppression, bloody wars and destruction is extensive and can be found in all periods of human history.

This points to the fact that the question of ‘truth’ and ‘being good’ is not only a question for the individual process, but also a question for the collective process, and here, in the collective case, this question is even more important, since in the event of an error not only individuals have to suffer negative effects, but rather very many; in the worst case, all of them.

To be continued …

COMMENTS

[*0] The meaning of the terms ‘objective, verifiable’ will be explained in more detail below.

[*1] In a system-theoretical view of the ‘human body’ system, one can formulate the working hypothesis that far more than 99% of the events in a human body are not conscious. You can find this frightening or reassuring. I tend towards the latter, towards ‘reassurance’. Because when you see what a human body as a ‘system’ is capable of doing on its own, every second, for many years, even decades, then this seems extremely reassuring in view of the many mistakes, even gross ones, that we can make with our small ‘consciousness’. In cooperation with other people, we can indeed dramatically improve our conscious human performance, but this is only ever possible if the system performance of a human body is maintained. After all, it contains 3.5 billion years of development work of the BIOM on this planet; the building blocks of this BIOM, the cells, function like a gigantic parallel computer, compared to which today’s technical supercomputers (including the much-vaunted ‘quantum computers’) look so small and weak that it is practically impossible to express this relationship.

[*2] An ‘everyday language’ always presupposes ‘the many’ who want to communicate with each other. One person alone cannot have a language that others should be able to understand.

[*3] A meaning relation actually does what is mathematically called a ‘mapping’: Elements of one kind (elements of the surface structure of the language) are mapped to elements of another kind (the potential meaning elements). While a mathematical mapping is normally fixed, the ‘real meaning relation’ can constantly change; it is ‘flexible’, part of a higher-level ‘learning process’ that constantly ‘readjusts’ the meaning relation depending on perception and internal states.

[*4] The contents of working hypothesis 2 originate from the findings of modern cognitive sciences (neuroscience, psychology, biology, linguistics, semiotics, …) and philosophy; they refer to many thousands of articles and books. Working hypothesis 2 therefore represents a highly condensed summary of all this. Direct citation is not possible in purely practical terms.

[*5] As is known from research on witness statements and from general perception research, in addition to all kinds of direct perception errors, there are many errors in the ‘interpretation of perception’ that are largely unconscious/automated. The actors are normally powerless against such errors; they simply do not notice them. Only methodically conscious controls of perception can partially draw attention to these errors.

[*6] Human knowledge is ‘notoriously prone to error’. There are many reasons for this. One lies in the way the brain itself works. ‘Correct’ knowledge is only possible if the current knowledge processes are repeatedly ‘compared’ and ‘checked’ so that they can be corrected. Anyone who does not regularly check the correctness will inevitably confirm incomplete and often incorrect knowledge. As we know, this does not prevent people from believing that everything they carry around in their heads is ‘true’. If there is a big problem in this world, then this is one of them: ignorance about one’s own ignorance.

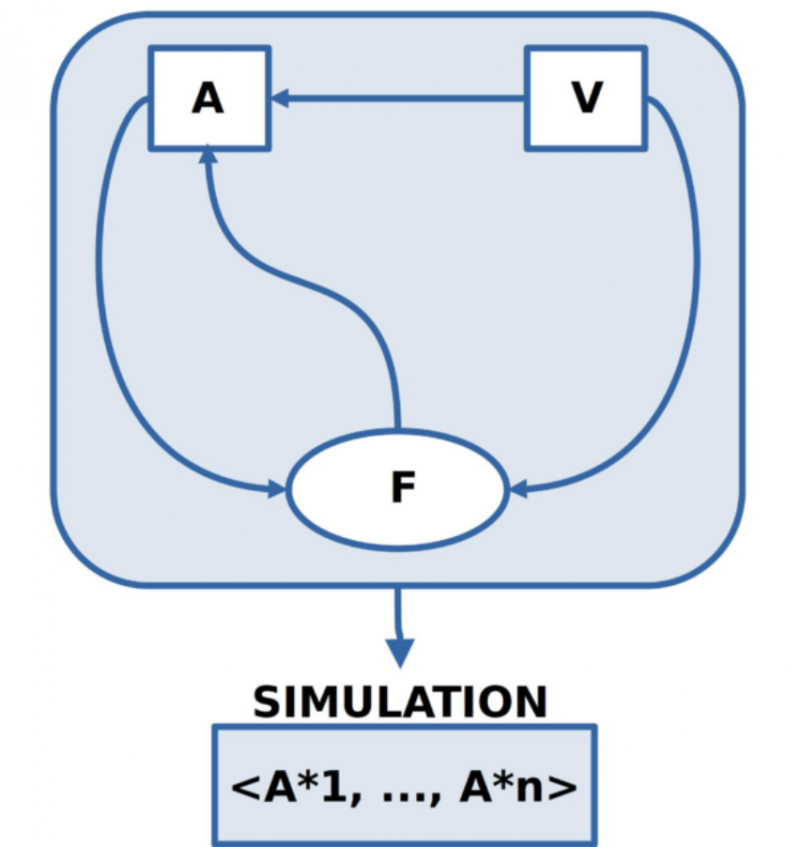

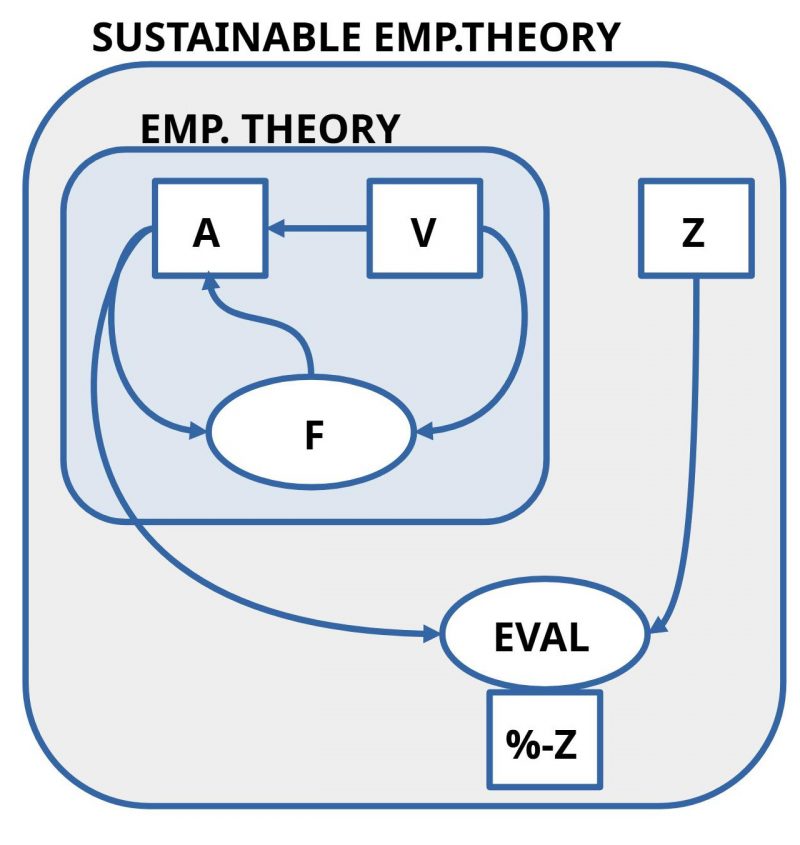

[*7] In the cultural history of mankind to date, it was only very late (about 500 years ago?) that a format of knowledge was discovered that enables any number of people to build up fact-based knowledge that, compared to all other known knowledge formats, enables the ‘best results’ (which of course does not completely rule out errors, but extremely minimizes them). This still revolutionary knowledge format has the name ’empirical theory’, which I have since expanded to ‘sustainable empirical theory’. On the one hand, we humans are the main source of ‘true knowledge’, but at the same time we ourselves are also the main source of ‘false knowledge’. At first glance, this seems like a ‘paradox’, but it has a ‘simple’ explanation, which at its root is ‘very profound’ (comparable to the cosmic background radiation, which is currently simple, but originates from the beginnings of the universe).

[*8] In terms of its architecture, our brain can open up any number of such meta-levels, but due to its concrete finiteness, it only offers a limited number of neurons for different tasks. For example, it is known (and has been experimentally proven several times) that our ‘working memory’ (also called ‘short-term memory’) is only limited to approx. 6-9 ‘units’ (whereby the term ‘unit’ must be defined depending on the context). So if we want to solve extensive tasks through our thinking, we need ‘external aids’ (sheet of paper and pen or a computer, …) to record the many aspects and write them down accordingly. Although today’s computers are not even remotely capable of replacing the complex thought processes of humans, they can be an almost irreplaceable tool for carrying out complex thought processes to a limited extent. But only if WE actually KNOW what we are doing!

[*9] The word ’emotion’ is a ‘collective term’ for many different phenomena and circumstances. Despite extensive research for over a hundred years, the various disciplines of psychology are still unable to offer a uniform picture, let alone a uniform ‘theory’ on the subject. This is not surprising, as much of the assumed emotions takes place largely ‘unconsciously’ or is only directly available as an ‘internal event’ in the individual. The only thing that seems to be clear is that we as humans are never ’emotion-free’ (this also applies to so-called ‘cool’ types, because the apparent ‘suppression’ or ‘repression’ of emotions is itself part of our innate emotionality).

[*10] Of course, emotions can also lead us seriously astray or even to our downfall (being wrong about other people, being wrong about ourselves, …). It is therefore not only important to ‘sort out’ the factual things in the world in a useful way through ‘learning’, but we must also actually ‘keep an eye on our own emotions’ and check when and how they occur and whether they actually help us. Primary emotions (such as hunger, sex drive, anger, addiction, ‘crushes’, …) are selective, situational, can develop great ‘psychological power’ and thus obscure our view of the possible or very probable ‘consequences’, which can be considerably damaging for us.

[*11] The term ‘narrative’ is increasingly used today to describe the fact that a group of people use a certain ‘image’, a certain ‘narrative’ in their thinking for their perception of the world in order to be able to coordinate their joint actions. Ultimately, this applies to all collective action, even for engineers who want to develop a technical solution. In this respect, the description in the German Wikipedia is a bit ‘narrow’: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrativ_(Sozialwissenschaften)

REFERENCES

The following sources are just a tiny selection from the many hundreds, if not thousands, of articles, books, audio documents and films on the subject. Nevertheless, they may be helpful for an initial introduction. The list will be expanded from time to time.

[1a] Propaganda, in the German Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda

[1b] Propaganda in the English Wikipedia : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda /*The English version appears more systematic, covers larger periods of time and more different areas of application */

[3] Propaganda der Russischen Föderation, hier: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda_der_Russischen_F%C3%B6deration (German source)

[6] Mischa Gabowitsch, Mai 2022, Von »Faschisten« und »Nazis«, https://www.blaetter.de/ausgabe/2022/mai/von-faschisten-und-nazis#_ftn4 (German source)