Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: info@uffmm.org

Aug 24, 2023 — Aug 29, 2023 (10:48h CET)

Attention: This text has been translated from a German source by using the software deepL for nearly 97 – 99% of the text! The diagrams of the German version have been left out.

CONTEXT

This text represents the outline of a talk given at the conference “AI – Text and Validity. How do AI text generators change scientific discourse?” (August 25/26, 2023, TU Darmstadt). [1] A publication of all lectures is planned by the publisher Walter de Gruyter by the end of 2023/beginning of 2024. This publication will be announced here then.

Start of the Lecture

Dear Auditorium,

This conference entitled “AI – Text and Validity. How do AI text generators change scientific discourses?” is centrally devoted to scientific discourses and the possible influence of AI text generators on these. However, the hot core ultimately remains the phenomenon of text itself, its validity.

In this conference many different views are presented that are possible on this topic.

TRANSDISCIPLINARY

My contribution to the topic tries to define the role of the so-called AI text generators by embedding the properties of ‘AI text generators’ in a ‘structural conceptual framework’ within a ‘transdisciplinary view’. This helps the specifics of scientific discourses to be highlighted. This can then result further in better ‘criteria for an extended assessment’ of AI text generators in their role for scientific discourses.

An additional aspect is the question of the structure of ‘collective intelligence’ using humans as an example, and how this can possibly unite with an ‘artificial intelligence’ in the context of scientific discourses.

‘Transdisciplinary’ in this context means to span a ‘meta-level’ from which it should be possible to describe today’s ‘diversity of text productions’ in a way that is expressive enough to distinguish ‘AI-based’ text production from ‘human’ text production.

HUMAN TEXT GENERATION

The formulation ‘scientific discourse’ is a special case of the more general concept ‘human text generation’.

This change of perspective is meta-theoretically necessary, since at first sight it is not the ‘text as such’ that decides about ‘validity and non-validity’, but the ‘actors’ who ‘produce and understand texts’. And with the occurrence of ‘different kinds of actors’ – here ‘humans’, there ‘machines’ – one cannot avoid addressing exactly those differences – if there are any – that play a weighty role in the ‘validity of texts’.

TEXT CAPABLE MACHINES

With the distinction in two different kinds of actors – here ‘humans’, there ‘machines’ – a first ‘fundamental asymmetry’ immediately strikes the eye: so-called ‘AI text generators’ are entities that have been ‘invented’ and ‘built’ by humans, it are furthermore humans who ‘use’ them, and the essential material used by so-called AI generators are again ‘texts’ that are considered a ‘human cultural property’.

In the case of so-called ‘AI-text-generators’, we shall first state only this much, that we are dealing with ‘machines’, which have ‘input’ and ‘output’, plus a minimal ‘learning ability’, and whose input and output can process ‘text-like objects’.

BIOLOGICAL — NON-BIOLOGICAL

On the meta-level, then, we are assumed to have, on the one hand, such actors which are minimally ‘text-capable machines’ – completely human products – and, on the other hand, actors we call ‘humans’. Humans, as a ‘homo-sapiens population’, belong to the set of ‘biological systems’, while ‘text-capable machines’ belong to the set of ‘non-biological systems’.

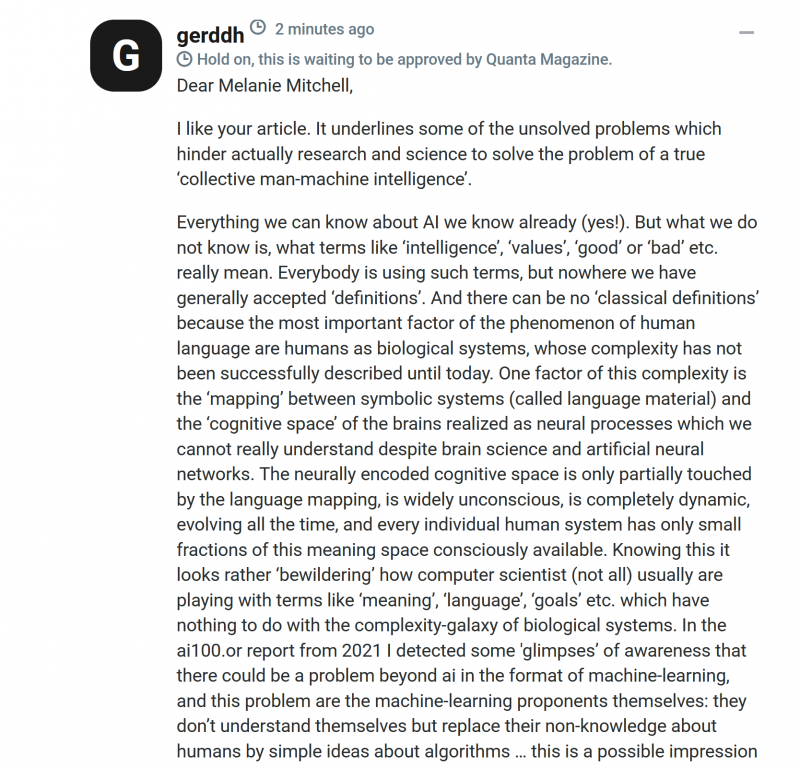

BLANK INTELLIGENCE TERM

The transformation of the term ‘AI text generator’ into the term ‘text capable machine’ undertaken here is intended to additionally illustrate that the widespread use of the term ‘AI’ for ‘artificial intelligence’ is rather misleading. So far, there exists today no general concept of ‘intelligence’ in any scientific discipline that can be applied and accepted beyond individual disciplines. There is no real justification for the almost inflationary use of the term AI today other than that the term has been so drained of meaning that it can be used anytime, anywhere, without saying anything wrong. Something that has no meaning can be neither true’ nor ‘false’.

PREREQUISITES FOR TEXT GENERATION

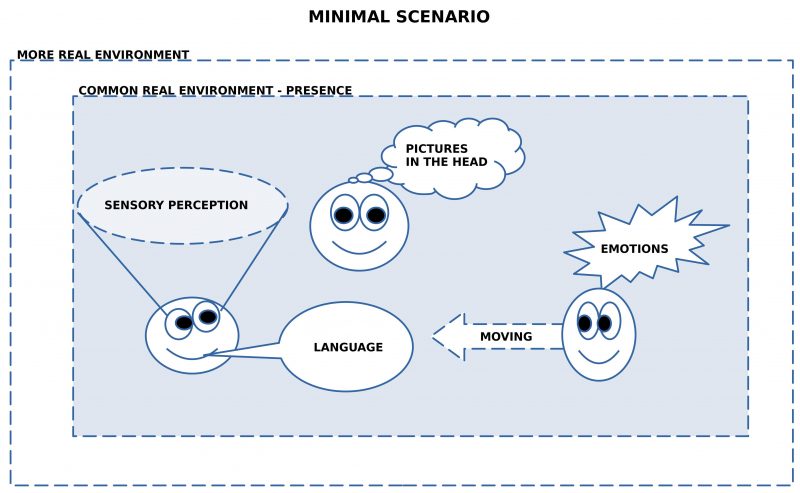

If now the homo-sapiens population is identified as the original actor for ‘text generation’ and ‘text comprehension’, it shall now first be examined which are ‘those special characteristics’ that enable a homo-sapiens population to generate and comprehend texts and to ‘use them successfully in the everyday life process’.

VALIDITY

A connecting point for the investigation of the special characteristics of a homo-sapiens text generation and a text understanding is the term ‘validity’, which occurs in the conference topic.

In the primary arena of biological life, in everyday processes, in everyday life, the ‘validity’ of a text has to do with ‘being correct’, being ‘appicable’. If a text is not planned from the beginning with a ‘fictional character’, but with a ‘reference to everyday events’, which everyone can ‘check’ in the context of his ‘perception of the world’, then ‘validity in everyday life’ has to do with the fact that the ‘correctness of a text’ can be checked. If the ‘statement of a text’ is ‘applicable’ in everyday life, if it is ‘correct’, then one also says that this statement is ‘valid’, one grants it ‘validity’, one also calls it ‘true’. Against this background, one might be inclined to continue and say: ‘If’ the statement of a text ‘does not apply’, then it has ‘no validity’; simplified to the formulation that the statement is ‘not true’ or simply ‘false’.

In ‘real everyday life’, however, the world is rarely ‘black’ and ‘white’: it is not uncommon that we are confronted with texts to which we are inclined to ascribe ‘a possible validity’ because of their ‘learned meaning’, although it may not be at all clear whether there is – or will be – a situation in everyday life in which the statement of the text actually applies. In such a case, the validity would then be ‘indeterminate’; the statement would be ‘neither true nor false’.

ASYMMETRY: APPLICABLE- NOT APPLICABLE

One can recognize a certain asymmetry here: The ‘applicability’ of a statement, its actual validity, is comparatively clear. The ‘not being applicable’, i.e. a ‘merely possible’ validity, on the other hand, is difficult to decide.

With this phenomenon of the ‘current non-decidability’ of a statement we touch both the problem of the ‘meaning’ of a statement — how far is at all clear what is meant? — as well as the problem of the ‘unfinishedness of our everyday life’, better known as ‘future’: whether a ‘current present’ continues as such, whether exactly like this, or whether completely different, depends on how we understand and estimate ‘future’ in general; what some take for granted as a possible future, can be simply ‘nonsense’ for others.

MEANING

This tension between ‘currently decidable’ and ‘currently not yet decidable’ additionally clarifies an ‘autonomous’ aspect of the phenomenon of meaning: if a certain knowledge has been formed in the brain and has been made usable as ‘meaning’ for a ‘language system’, then this ‘associated’ meaning gains its own ‘reality’ for the scope of knowledge: it is not the ‘reality beyond the brain’, but the ‘reality of one’s own thinking’, whereby this reality of thinking ‘seen from outside’ has something like ‘being virtual’.

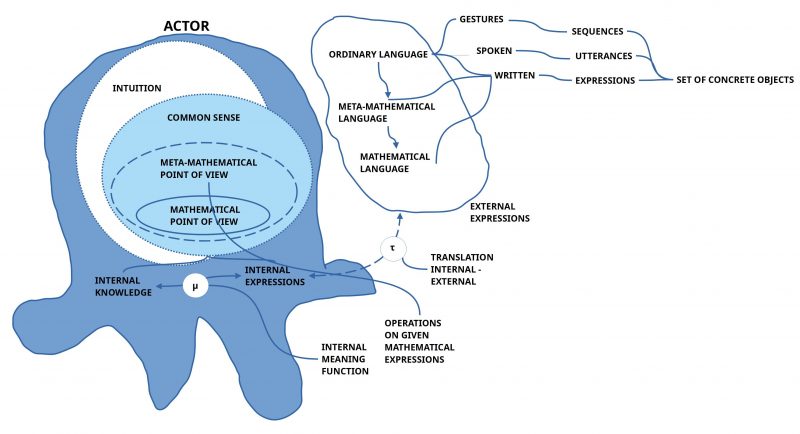

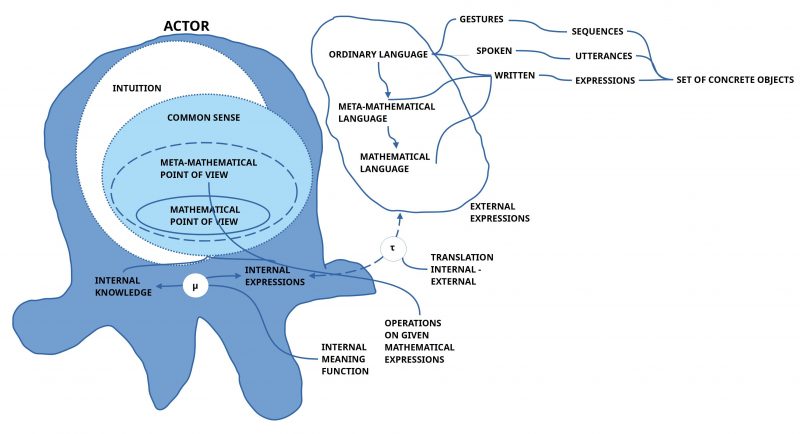

If one wants to talk about this ‘special reality of meaning’ in the context of the ‘whole system’, then one has to resort to far-reaching assumptions in order to be able to install a ‘conceptual framework’ on the meta-level which is able to sufficiently describe the structure and function of meaning. For this, the following components are minimally assumed (‘knowledge’, ‘language’ as well as ‘meaning relation’):

KNOWLEDGE: There is the totality of ‘knowledge’ that ‘builds up’ in the homo-sapiens actor in the course of time in the brain: both due to continuous interactions of the ‘brain’ with the ‘environment of the body’, as well as due to interactions ‘with the body itself’, as well as due to interactions ‘of the brain with itself’.

LANGUAGE: To be distinguished from knowledge is the dynamic system of ‘potential means of expression’, here simplistically called ‘language’, which can unfold over time in interaction with ‘knowledge’.

MEANING RELATIONSHIP: Finally, there is the dynamic ‘meaning relation’, an interaction mechanism that can link any knowledge elements to any language means of expression at any time.

Each of these mentioned components ‘knowledge’, ‘language’ as well as ‘meaning relation’ is extremely complex; no less complex is their interaction.

FUTURE AND EMOTIONS

In addition to the phenomenon of meaning, it also became apparent in the phenomenon of being applicable that the decision of being applicable also depends on an ‘available everyday situation’ in which a current correspondence can be ‘concretely shown’ or not.

If, in addition to a ‘conceivable meaning’ in the mind, we do not currently have any everyday situation that sufficiently corresponds to this meaning in the mind, then there are always two possibilities: We can give the ‘status of a possible future’ to this imagined construct despite the lack of reality reference, or not.

If we would decide to assign the status of a possible future to a ‘meaning in the head’, then there arise usually two requirements: (i) Can it be made sufficiently plausible in the light of the available knowledge that the ‘imagined possible situation’ can be ‘transformed into a new real situation’ in the ‘foreseeable future’ starting from the current real situation? And (ii) Are there ‘sustainable reasons’ why one should ‘want and affirm’ this possible future?

The first requirement calls for a powerful ‘science’ that sheds light on whether it can work at all. The second demand goes beyond this and brings the seemingly ‘irrational’ aspect of ’emotionality’ into play under the garb of ‘sustainability’: it is not simply about ‘knowledge as such’, it is also not only about a ‘so-called sustainable knowledge’ that is supposed to contribute to supporting the survival of life on planet Earth — and beyond –, it is rather also about ‘finding something good, affirming something, and then also wanting to decide it’. These last aspects are so far rather located beyond ‘rationality’; they are assigned to the diffuse area of ’emotions’; which is strange, since any form of ‘usual rationality’ is exactly based on these ’emotions’.[2]

SCIENTIFIC DISCOURSE AND EVERYDAY SITUATIONS

In the context of ‘rationality’ and ’emotionality’ just indicated, it is not uninteresting that in the conference topic ‘scientific discourse’ is thematized as a point of reference to clarify the status of text-capable machines.

The question is to what extent a ‘scientific discourse’ can serve as a reference point for a successful text at all?

For this purpose it can help to be aware of the fact that life on this planet earth takes place at every moment in an inconceivably large amount of ‘everyday situations’, which all take place simultaneously. Each ‘everyday situation’ represents a ‘present’ for the actors. And in the heads of the actors there is an individually different knowledge about how a present ‘can change’ or will change in a possible future.

This ‘knowledge in the heads’ of the actors involved can generally be ‘transformed into texts’ which in different ways ‘linguistically represent’ some of the aspects of everyday life.

The crucial point is that it is not enough for everyone to produce a text ‘for himself’ alone, quite ‘individually’, but that everyone must produce a ‘common text’ together ‘with everyone else’ who is also affected by the everyday situation. A ‘collective’ performance is required.

Nor is it a question of ‘any’ text, but one that is such that it allows for the ‘generation of possible continuations in the future’, that is, what is traditionally expected of a ‘scientific text’.

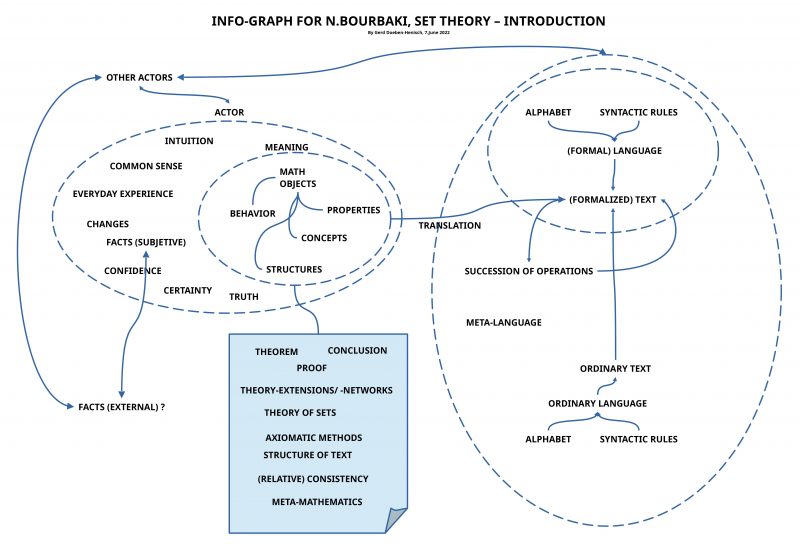

From the extensive discussion — since the times of Aristotle — of what ‘scientific’ should mean, what a ‘theory’ is, what an ’empirical theory’ should be, I sketch what I call here the ‘minimal concept of an empirical theory’.

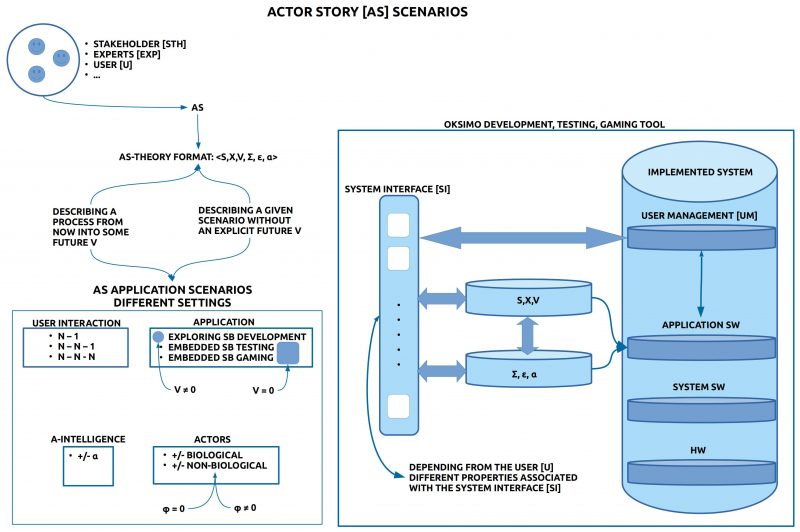

- The starting point is a ‘group of people’ (the ‘authors’) who want to create a ‘common text’.

- This text is supposed to have the property that it allows ‘justifiable predictions’ for possible ‘future situations’, to which then ‘sometime’ in the future a ‘validity can be assigned’.

- The authors are able to agree on a ‘starting situation’ which they transform by means of a ‘common language’ into a ‘source text’ [A].

- It is agreed that this initial text may contain only ‘such linguistic expressions’ which can be shown to be ‘true’ ‘in the initial situation’.

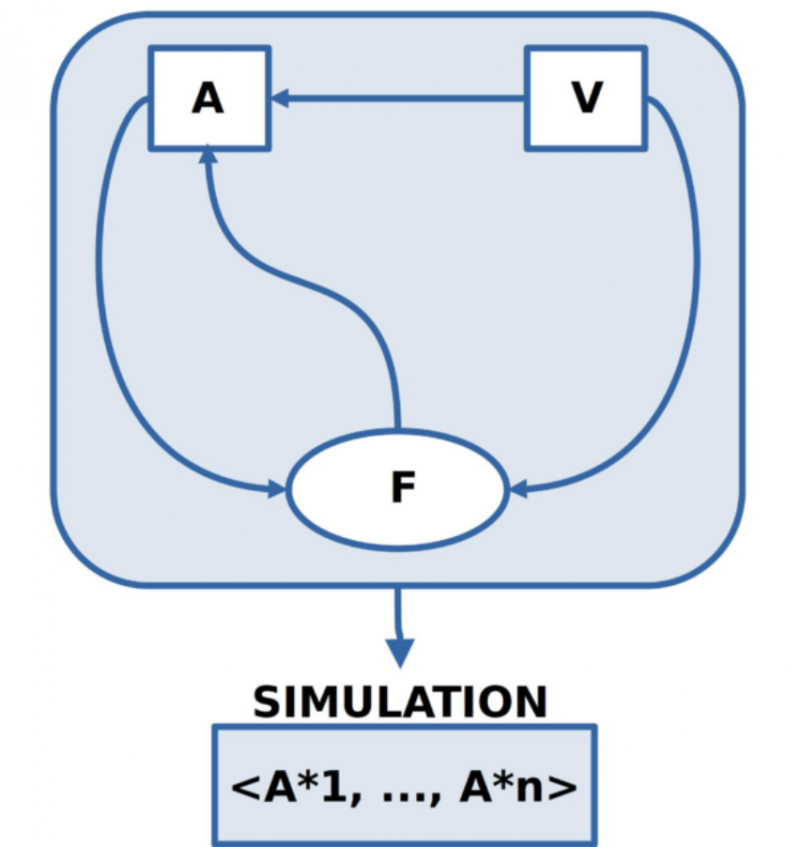

- In another text, the authors compile a set of ‘rules of change’ [V] that put into words ‘forms of change’ for a given situation.

- Also in this case it is considered as agreed that only ‘such rules of change’ may be written down, of which all authors know that they have proved to be ‘true’ in ‘preceding everyday situations’.

- The text with the rules of change V is on a ‘meta-level’ compared to the text A about the initial situation, which is on an ‘object-level’ relative to the text V.

- The ‘interaction’ between the text V with the change rules and the text A with the initial situation is described in a separate ‘application text’ [F]: Here it is described when and how one may apply a change rule (in V) to a source text A and how this changes the ‘source text A’ to a ‘subsequent text A*’.

- The application text F is thus on a next higher meta-level to the two texts A and V and can cause the application text to change the source text A.

- The moment a new subsequent text A* exists, the subsequent text A* becomes the new initial text A.

- If the new initial text A is such that a change rule from V can be applied again, then the generation of a new subsequent text A* is repeated.

- This ‘repeatability’ of the application can lead to the generation of many subsequent texts <A*1, …, A*n>.

- A series of many subsequent texts <A*1, …, A*n> is usually called a ‘simulation’.

- Depending on the nature of the source text A and the nature of the change rules in V, it may be that possible simulations ‘can go quite differently’. The set of possible scientific simulations thus represents ‘future’ not as a single, definite course, but as an ‘arbitrarily large set of possible courses’.

- The factors on which different courses depend are manifold. One factor are the authors themselves. Every author is, after all, with his corporeality completely himself part of that very empirical world which is to be described in a scientific theory. And, as is well known, any human actor can change his mind at any moment. He can literally in the next moment do exactly the opposite of what he thought before. And thus the world is already no longer the same as previously assumed in the scientific description.

Even this simple example shows that the emotionality of ‘finding good, wanting, and deciding’ lies ahead of the rationality of scientific theories. This continues in the so-called ‘sustainability discussion’.

SUSTAINABLE EMPIRICAL THEORY

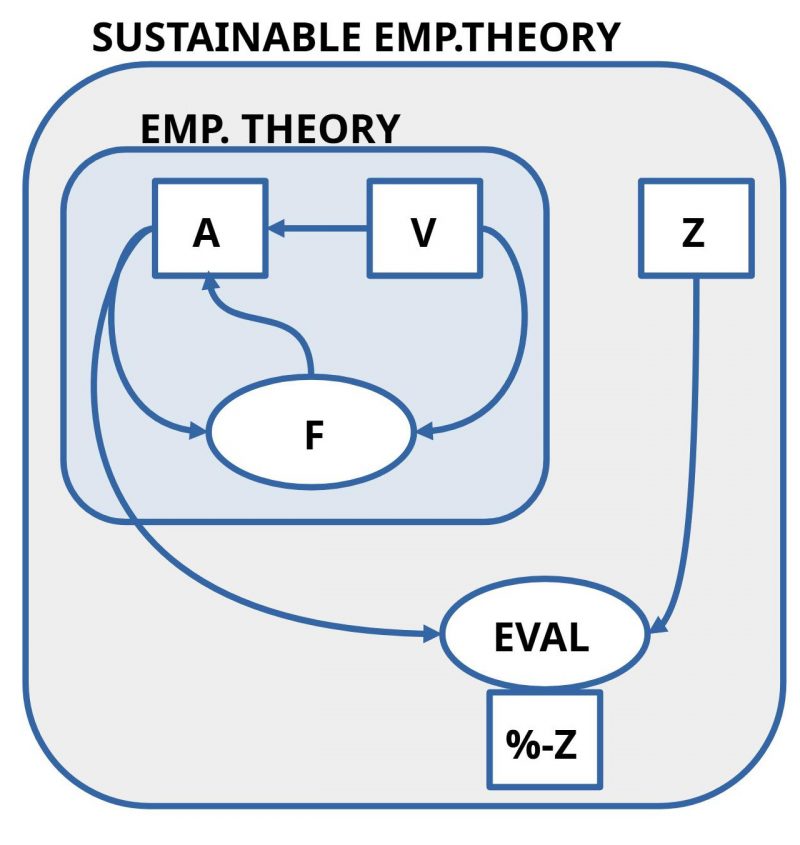

With the ‘minimal concept of an empirical theory (ET)’ just introduced, a ‘minimal concept of a sustainable empirical theory (NET)’ can also be introduced directly.

While an empirical theory can span an arbitrarily large space of grounded simulations that make visible the space of many possible futures, everyday actors are left with the question of what they want to have as ‘their future’ out of all this? In the present we experience the situation that mankind gives the impression that it agrees to destroy the life beyond the human population more and more sustainably with the expected effect of ‘self-destruction’.

However, this self-destruction effect, which can be predicted in outline, is only one variant in the space of possible futures. Empirical science can indicate it in outline. To distinguish this variant before others, to accept it as ‘good’, to ‘want’ it, to ‘decide’ for this variant, lies in that so far hardly explored area of emotionality as root of all rationality.[2]

If everyday actors have decided in favor of a certain rationally lightened variant of possible future, then they can evaluate at any time with a suitable ‘evaluation procedure (EVAL)’ how much ‘percent (%) of the properties of the target state Z’ have been achieved so far, provided that the favored target state is transformed into a suitable text Z.

In other words, the moment we have transformed everyday scenarios into a rationally tangible state via suitable texts, things take on a certain clarity and thereby become — in a sense — simple. That we make such transformations and on which aspects of a real or possible state we then focus is, however, antecedent to text-based rationality as an emotional dimension.[2]

MAN-MACHINE

After these preliminary considerations, the final question is whether and how the main question of this conference, “How do AI text generators change scientific discourse?” can be answered in any way?

My previous remarks have attempted to show what it means for humans to collectively generate texts that meet the criteria for scientific discourse that also meets the requirements for empirical or even sustained empirical theories.

In doing so, it becomes apparent that both in the generation of a collective scientific text and in its application in everyday life, a close interrelation with both the shared experiential world and the dynamic knowledge and meaning components in each actor play a role.

The aspect of ‘validity’ is part of a dynamic world reference whose assessment as ‘true’ is constantly in flux; while one actor may tend to say “Yes, can be true”, another actor may just tend to the opposite. While some may tend to favor possible future option X, others may prefer future option Y. Rational arguments are absent; emotions speak. While one group has just decided to ‘believe’ and ‘implement’ plan Z, the others turn away, reject plan Z, and do something completely different.

This unsteady, uncertain character of future-interpretation and future-action accompanies the Homo Sapiens population from the very beginning. The not understood emotional complex constantly accompanies everyday life like a shadow.

Where and how can ‘text-enabled machines’ make a constructive contribution in this situation?

Assuming that there is a source text A, a change text V and an instruction F, today’s algorithms could calculate all possible simulations faster than humans could.

Assuming that there is also a target text Z, today’s algorithms could also compute an evaluation of the relationship between a current situation as A and the target text Z.

In other words: if an empirical or a sustainable-empirical theory would be formulated with its necessary texts, then a present algorithm could automatically compute all possible simulations and the degree of target fulfillment faster than any human alone.

But what about the (i) elaboration of a theory or (ii) the pre-rational decision for a certain empirical or even sustainable-empirical theory ?

A clear answer to both questions seems hardly possible to me at the present time, since we humans still understand too little how we ourselves collectively form, select, check, compare and also reject theories in everyday life.

My working hypothesis on the subject is: that we will very well need machines capable of learning in order to be able to fulfill the task of developing useful sustainable empirical theories for our common everyday life in the future. But when this will happen in reality and to what extent seems largely unclear to me at this point in time.[2]

COMMENTS

[1] https://zevedi.de/en/topics/ki-text-2/

[2] Talking about ’emotions’ in the sense of ‘factors in us’ that move us to go from the state ‘before the text’ to the state ‘written text’, that hints at very many aspects. In a small exploratory text “State Change from Non-Writing to Writing. Working with chatGPT4 in parallel” ( https://www.uffmm.org/2023/08/28/state-change-from-non-writing-to-writing-working-with-chatgpt4-in-parallel/ ) the author has tried to address some of these aspects. While writing it becomes clear that very many ‘individually subjective’ aspects play a role here, which of course do not appear ‘isolated’, but always flash up a reference to concrete contexts, which are linked to the topic. Nevertheless, it is not the ‘objective context’ that forms the core statement, but the ‘individually subjective’ component that appears in the process of ‘putting into words’. This individual subjective component is tentatively used here as a criterion for ‘authentic texts’ in comparison to ‘automated texts’ like those that can be generated by all kinds of bots. In order to make this difference more tangible, the author decided to create an ‘automated text’ with the same topic at the same time as the quoted authentic text. For this purpose he used chatGBT4 from openAI. This is the beginning of a philosophical-literary experiment, perhaps to make the possible difference more visible in this way. For purely theoretical reasons, it is clear that a text generated by chatGBT4 can never generate ‘authentic texts’ in origin, unless it uses as a template an authentic text that it can modify. But then this is a clear ‘fake document’. To prevent such an abuse, the author writes the authentic text first and then asks chatGBT4 to write something about the given topic without chatGBT4 knowing the authentic text, because it has not yet found its way into the database of chatGBT4 via the Internet.