(First: June 9, 2023 – Last change: June 10, 2023)

Comment: This post is a translation from a German text in my blog ‘cognitiveagent.org’ with the aid of the deepL software

CONTEXT

The current phase of my thinking continues to revolve around the question how the various states of knowledge relate to each other: the many individual scientific disciplines drift side by side; philosophy continues to claim supremacy, but cannot really locate itself convincingly; and everyday thinking continues to run its course unperturbed with the conviction that ‘everything is clear’, that you just have to look at it ‘as it is’. Then the different ‘religious views’ come around the corner with a very high demand and a simultaneous prohibition not to look too closely. … and much more.

INTENTION

In the following text three fundamental ways of looking at our present world are outlined and at the same time they are put in relation to each other. Some hitherto unanswered questions can possibly be answered better, but many new questions arise as well. When ‘old patterns of thinking’ are suspended, many (most? all?) of the hitherto familiar patterns of thinking have to be readjusted. All of a sudden they are simply ‘wrong’ or strongly ‘in need of repair’.

Unfortunately it is only a ‘sketch’.[1]

THOUGHTS IN EVERYDAY

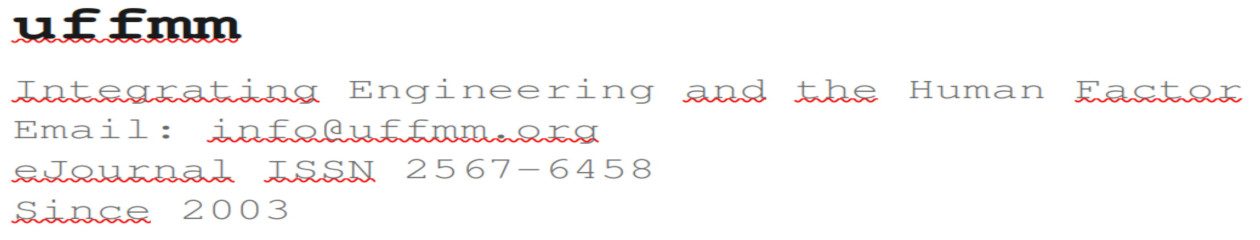

FIG. 1: In everyday thinking, every human being (a ‘homo sapiens’ (HS)) assumes that what he knows of a ‘real world’ is what he ‘perceives’. That there is this real world with its properties, he is – more or less – ‘aware’ of, there is no need to discuss about it specially. That, what ‘is, is’.

… much could be said …

PHILOSOPHICAL THINKING

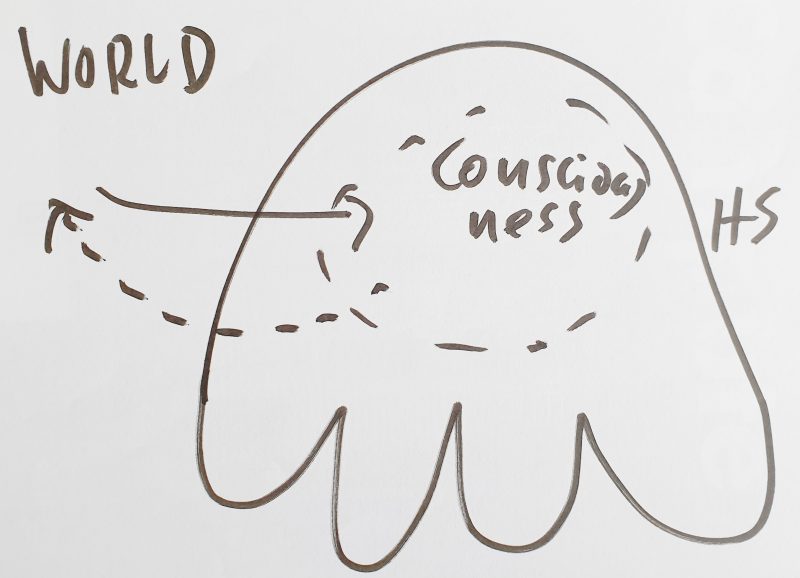

FIG. 2: Philosophical thinking starts where one notices that the ‘real world’ is not perceived by all people in ‘the same way’ and even less ‘imagined’ in the same way. Some people have ‘their ideas’ about the real world that are strikingly ‘different’ from other people’s ideas, and yet they insist that the world is exactly as they imagine it. From this observation in everyday life, many new questions can arise. The answers to these questions are as manifold as there were and are people who gave or still give themselves to these philosophical questions.

… famous examples: Plato’s allegory of the cave suggests that the contents of our consciousness are perhaps not ‘the things themselves’ but only the ‘shadows’ of what is ultimately ‘true’ … Descartes‘ famous ‘cogito ergo sum’ brings into play the aspect that the contents of consciousness also say something about himself who ‘consciously perceives’ such contents …. the ‘existence of the contents’ presupposes his ‘existence as thinker’, without which the existence of the contents would not be possible at all …what does this tell us? … Kant’s famous ‘thing in itself’ (‘Ding an sich’) can be referred to the insight that the concrete, fleeting perceptions can never directly show the ‘world as such’ in its ‘generality’. This lies ‘somewhere behind’, hard to grasp, actually not graspable at all? ….

… many things could be said …

EMPIRICAL-THEORETICAL THINKING

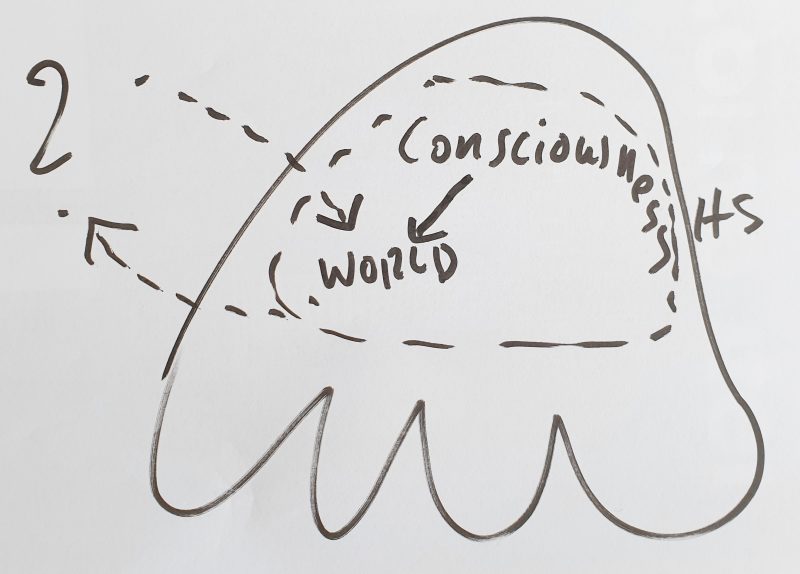

FIG. 3: The concept of an ’empirical theory’ developed very late in the documented history of man on this planet. On the one hand philosophically inspired, on the other hand independent of the widespread forms of philosophy, but very strongly influenced by logical and mathematical thinking, the new ’empirical theoretical’ thinking settled exactly at this breaking point between ‘everyday thinking’ and ‘theological’ as well as ‘strongly metaphysical philosophical thinking’. The fact that people could make statements about the world ‘with the chest tone of conviction’, although it was not possible to show ‘common experiences of the real world’, which ‘corresponded’ with the expressed statements, inspired individual people to investigate the ‘experiential (empirical) world’ in such a way that everyone else could have the ‘same experiences’ with ‘the same procedure’. These ‘transparent procedures’ were ‘repeatable’ and such procedures became what was later called ’empirical experiment’ or then, one step further, ‘measurement’. In ‘measuring’ one compares the ‘result’ of a certain experimental procedure with a ‘previously defined standard object’ (‘kilogram’, ‘meter’, …).

This procedure led to the fact that – at least the experimenters – ‘learned’ that our knowledge about the ‘real world’ breaks down into two components: there is the ‘general knowledge’ what our language can articulate, with terms that do not automatically have to have something to do with the ‘experiential world’, and such terms that can be associated with experimental experiences, and in such a way that other people, if they engage in the experimental procedure, can also repeat and thereby confirm these experiences. A rough distinction between these two kinds of linguistic expressions might be ‘fictive’ expressions with unexplained claims to experience, and ’empirical’ expressions with confirmed claims to experience.

Since the beginning of the new empirical-theoretical way of thinking in the 17th century, it took at least 300 years until the concept of an ’empirical theory’ was consolidated to such an extent that it became a defining paradigm in many areas of science. However, many methodological questions remained controversial or even ‘unsolved’.

DATA and THEORY

For many centuries, the ‘misuse of everyday language’ for enabling ’empirically unverifiable statements’ was directly chalked up to this everyday language and the whole everyday language was discredited as ‘source of untruths’. A liberation from this ‘ monster of everyday language’ was increasingly sought in formal artificial languages or then in modern axiomatized mathematics, which had entered into a close alliance with modern formal logic (from the end of the 19th century). The expression systems of modern formal logic or then of modern formal mathematics had as such (almost) no ‘intrinsic meaning’. They had to be introduced explicitly on a case-by-case basis. A ‘formal mathematical theory’ could be formulated in such a way that it allowed ‘logical inferences’ even without ‘explicit assignment’ of an ‘external meaning’, which allowed certain formal expressions to be called ‘formally true’ or ‘formally false’.

This seemed very ‘reassuring’ at first sight: mathematics as such is not a place of ‘false’ or ‘foisted’ truths.

The intensive use of formal theories in connection with experience-based experiments, however, then gradually made clear that a single measured value as such does not actually have any ‘meaning’ either: what is it supposed to ‘mean’ that at a certain ‘time’ at a certain ‘place’ one establishes an ‘experienceable state’ with certain ‘properties’, ideally comparable to a previously agreed ‘standard object’? ‘Expansions’ of bodies can change, ‘weight’ and ‘temperature’ as well. Everything can change in the world of experience, fast, slow, … so what can a single isolated measured value say?

It dawned to some – not only to the experience-based researchers, but also to some philosophers – that single measured values only get a ‘meaning’, a possible ‘sense’, if one can at least establish ‘relations’ between single measured values: Relations ‘in time’ (before – after), relations at/in place (higher – lower, next to each other, …), ‘interrelated quantities’ (objects – areas, …), and that furthermore the different ‘relations’ themselves again need a ‘conceptual context’ (single – quantity, interactions, causal – non-causal, …).

Finally, it became clear that single measured values needed ‘class terms’, so that they could be classified somehow: abstract terms like ‘tree’, ‘plant’, ‘cloud’, ‘river’, ‘fish’ etc. became ‘collection points’, where one could deliver ‘single observations’. With this, hundreds and hundreds of single values could then be used, for example, to characterize the abstract term ‘tree’ or ‘plant’ etc.

This distinction into ‘single, concrete’ and ‘abstract, general’ turns out to be fundamental. It also made clear that the classification of the world by means of such abstract terms is ultimately ‘arbitrary’: both ‘which terms’ one chooses is arbitrary, and the assignment of individual experiential data to abstract terms is not unambiguously settled in advance. The process of assigning individual experiential data to particular terms within a ‘process in time’ is itself strongly ‘hypothetical’ and itself in turn part of other ‘relations’ which can provide additional ‘criteria’ as to whether date X is more likely to belong to term A or more likely to belong to term B (biology is full of such classification problems).

Furthermore, it became apparent that mathematics, which comes across as so ‘innocent’, can by no means be regarded as ‘innocent’ on closer examination. The broad discussion of philosophy of science in the 20th century brought up many ‘artifacts’ which can at least easily ‘corrupt’ the description of a dynamic world of experience.

Thus it belongs to formal mathematical theories that they can operate with so-called ‘all- or particular statements’. Mathematically it is important that I can talk about ‘all’ elements of a domain/set. Otherwise talking becomes meaningless. If I now choose a formal mathematical system as conceptual framework for a theory which describes ’empirical facts’ in such a way that inferences become possible which are ‘true’ in the sense of the theory and thus become ‘predictions’ which assert that a certain fact will occur either ‘absolutely’ or with a certain probability X greater than 50%, then two different worlds unite: the fragmentary individual statements about the world of experience become embedded in ‘all-statements’ which in principle say more than empirical data can provide.

At this point it becomes visible that mathematics, which appears to be so ‘neutral’, does exactly the same job as ‘everyday language’ with its ‘abstract concepts’: the abstract concepts of everyday language always go beyond the individual case (otherwise we could not say anything at all in the end), but just by this they allow considerations and planning, as we appreciate them so much in mathematical theories.

Empirical theories in the format of formal mathematical theories have the further problem that they as such have (almost) no meanings of their own. If one wants to relate the formal expressions to the world of experience, then one has to explicitly ‘construct a meaning’ (with the help of everyday language!) for each abstract concept of the formal theory (or also for each formal relation or also for each formal operator) by establishing a ‘mapping’/an ‘assignment’ between the abstract constructs and certain provable facts of experience. What may sound so simple here at first sight has turned out to be an almost unsolvable problem in the course of the last 100 years. Now it does not follow that one should not do it at all; but it does draw attention to the fact that the choice of a formal mathematical theory need not automatically be a good solution.

… many things could still be said …

INFERENCE and TRUTH

A formal mathematical theory can derive certain statements as formally ‘true’ or ‘false’ from certain ‘assumptions’. This is possible because there are two basic assumptions: (i) All formal expressions have an ‘abstract truth value’ as ‘abstractly true’ or just as ‘abstractly not true’. Furthermore, there is a so-called ‘formal notion of inference’ which determines whether and how one can ‘infer’ other formal expressions from a given ‘set of formal expressions’ with agreed abstract truth values and a well-defined ‘form’. This ‘derivation’ consists of ‘operations over the signs of the formal expressions’. The formal expressions are here ‘objects’ of the notion of inference, which is located on a ‘level higher’, on a ‘meta-level 1’. The inference term is insofar a ‘formal theory’ of its own, which speaks about certain ‘objects of a deeper level’ in the same way as the abstract terms of a theory (or of everyday language) speak about concrete facts of experience. The interaction of the notion of inference (at meta-level 1) and the formal expressions as objects presupposes its own ‘interpretive relation’ (ultimately a kind of ‘mapping’), which in turn is located at yet another level – meta-level 2. This interpretive relation uses both the formal expressions (with their truth values!) and the inference term as ‘objects’ to install an interpretive relation between them. Normally, this meta-level 2 is handled by the everyday language, and the implicit interpretive relation is located ‘in the minds of mathematicians (actually, in the minds of logicians)’, who assume that their ‘practice of inference’ provides enough experiential data to ‘understand’ the ‘content of the meaning relation’.

It had been Kurt Gödel [2], who in 1930/31 tried to formalize the ‘intuitive procedure’ of meta-proofs itself (by means of the famous Gödelization) and thus made the meta-level 3 again a new ‘object’, which can be discussed explicitly. Following Gödel’s proof, there were further attempts to formulate this meta-level 3 again in a different ways or even to formalize a meta-level 4. But these approaches remained so far without clear philosophical result.

It seems to be clear only that the ability of the human brain to open again and again new meta-levels, in order to analyze and discuss with it previously formulated facts, is in principle unlimited (only limited by the finiteness of the brain, its energy supply, the time, and similar material factors).

An interesting special question is whether the formal inference concept of formal mathematics applied to experience facts of a dynamic empirical world is appropriate to the specific ‘world dynamics’ at all? For the area of the ‘apparently material structures’ of the universe, modern physics has located multiple phenomena which simply elude classical concepts. A ‘matter’, which is at the same time ‘energy’, tends to be no longer classically describable, and quantum physics is – despite all ‘modernity’ – in the end still a ‘classical thinking’ within the framework of a formal mathematics, which does not possess many properties from the approach, which, however, belong to the experienceable world.

This limitation of a formal-mathematical physical thinking shows up especially blatantly at the example of those phenomena which we call ‘life’. The experience-based phenomena that we associate with ‘living (= biological) systems’ are, at first sight, completely material structures, however, they have dynamic properties that say more about the ‘energy’ that gives rise to them than about the materiality by means of which they are realized. In this respect, implicit energy is the real ‘information content’ of living systems, which are ‘radically free’ systems in their basic structure, since energy appears as ‘unbounded’. The unmistakable tendency of living systems ‘out of themselves’ to always ‘enable more complexity’ and to integrate contradicts all known physical principles. ‘Entropy’ is often used as an argument to relativize this form of ‘biological self-dynamics’ with reference to a simple ‘upper bound’ as ‘limitation’, but this reference does not completely nullify the original phenomenon of the ‘living’.

It becomes especially exciting if one dares to ask the question of ‘truth’ at this point. If one locates the meaning of the term ‘truth’ first of all in the situation in which a biological system (here the human being) can establish a certain ‘correspondence’ between its abstract concepts and such concrete knowledge structures within its thinking, which can be related to properties of an experiential world through a process of interaction, not only as a single individual but together with other individuals, then any abstract system of expression (called ‘language’) has a ‘true relation to reality’ only to the extent that there are biological systems that can establish such relations. And these references further depend on the structure of perception and the structure of thought of these systems; these in turn depend on the nature of bodies as the context of brains, and bodies in turn depend on both the material structure and dynamics of the environment and the everyday social processes that largely determine what a member of a society can experience, learn, work, plan, and do. Whatever an individual can or could do, society either amplifies or ‘freezes’ the individual’s potential. ‘Truth’ exists under these conditions as a ‘free-moving parameter’ that is significantly affected by the particular process environment. Talk of ‘cultural diversity’ can be a dangerous ‘trivialization’ of massive suppression of ‘alternative processes of learning and action’ that are ‘withdrawn’ from a society because it ‘locks itself in’. Ignorance tends not to be a good advisor. However, knowledge as such does not guarantee ‘right’ action either. The ‘process of freedom’ on planet Earth is a ‘galactic experiment’, the seriousness and extent of which is hardly seen so far.

COMMENTS

[1] References are omitted here. Many hundreds of texts would have to be mentioned. No sketch can do that.

[2] See for the ‘incompleteness theorems’ of Kurt Gödel (1930, published 1931): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurt_G%C3%B6del#Incompleteness_theorems