This text is part of the text “Rebooting Humanity”

(The German Version can be found HERE)

Author No. 1 (Gerd Doeben-Henisch)

Contact: info@uffmm.org

(Start: June 5, 2024, Last change: June 7, 2024)

Starting Point

A ‘text’ shall be written that speaks about the world, including all living beings, with ‘humans’ as the authors in the first instance. So far, we know of no cases where animals or plants write texts themselves: their view of life. We only know of humans who write from ‘their human perspective’ about life, animals, and plants. Much can be criticized about this approach. Upon further reflection, one might even realize that ‘humans writing about other humans and themselves’ is not so trivial either. Even humans writing ‘about themselves’ is prone to errors, can go completely ‘awry,’ can be entirely ‘wrong,’ which raises the question of what is ‘true’ or ‘false.’ Therefore, we should spend some thoughts on how we humans can talk about the world and ourselves in a way that gives us a chance not just to ‘fantasize,’ but to grasp something that is ‘real,’ something that describes what truly characterizes us as humans, as living beings, as inhabitants of this planet… but then the question pops up again, what is ‘real’? Are we caught in a cycle of questions with answers, where the answers themselves are again questions upon closer inspection?

First Steps

Life on Planet Earth

At the start of writing, we assume that there is a ‘Planet Earth’ and on this planet there is something we call ‘life,’ and we humans—belonging to the species Homo sapiens—are part of it.

Language

We also assume that we humans have the ability to communicate with each other using sounds. These sounds, which we use for communication, we call here ‘speech sounds’ to indicate that the totality of sounds for communication forms a ‘system’ which we ultimately call ‘language.’

Meaning

Since we humans on this planet can use completely different sounds for the ‘same objects’ in the same situation, it suggests that the ‘meaning’ of speech sounds is not firmly tied to the speech sounds themselves, but somehow has to do with what happens ‘in our minds.’ Unfortunately, we cannot look ‘into our minds.’ It seems a lot happens there, but this happening in the mind is ‘invisible.’ Nevertheless, in ‘everyday life,’ we experience that we can ‘agree’ with others whether it is currently ‘raining’ or if it smells ‘bad’ or if there is a trash bin on the sidewalk blocking the way, etc. So somehow, the ‘happenings in the mind’ seem to have certain ‘agreements’ among different people, so that not only I see something specific, but the other person does too, and we can even use the same speech sounds for it. And since a program like chatGPT can translate my German speech sounds, e.g., into English speech sounds, I can see that another person who does not speak German, instead of my word ‘Mülltonne,’ uses the word ‘trash bin’ and then nods in agreement: ‘Yes, there is a trash bin.’ Would that be a case for a ‘true statement’?

Changes and Memories

Since we experience daily how everyday life constantly ‘changes,’ we know that something that just found agreement may no longer find it the next moment because the trash bin is no longer there. We can only notice these changes because we have something called ‘memory’: we can remember that just now at a specific place there was a trash bin, but now it’s not. Or is this memory just an illusion? Can I trust my memory? If now everyone else says there was no trash bin, but I remember there was, what does that mean?

Concrete Body

Yes, and then my body: time and again I need to drink something, eat something, I’m not arbitrarily fast, I need some space, … my body is something very concrete, with all sorts of ‘sensations,’ ‘needs,’ a specific ‘shape,’ … and it changes over time: it grows, it ages, it can become sick, … is it like a ‘machine’?

Galaxies of Cells

Today we know that our human body resembles less a ‘machine’ and more a ‘galaxy of cells.’ Our body has about 37 trillion (10¹²) body cells with another 100 trillion cells in the gut that are vital for our digestive system, and these cells together form the ‘body system.’ The truly incomprehensible thing is that these approximately 140 trillion cells are each completely autonomous living beings, with everything needed for life. And if you know how difficult it is for us as humans to maintain cooperation among just five people over a long period, then you can at least begin to appreciate what it means that 140 trillion beings manage to communicate and coordinate actions every second—over many years, even decades—so that the masterpiece ‘human body’ exists and functions.

Origin as a Question

And since there is no ‘commander’ who constantly tells all the cells what to do, this ‘miracle of the human system’ expands further into the dimension of where the concept comes from that enables this ‘super-galaxy of cells’ to be as they are. How does this work? How did it arise?

Looking Behind Phenomena

In the further course, it will be important to gradually penetrate the ‘surface of everyday phenomena’ starting from everyday life, to make visible those structures that are ‘behind the phenomena,’ those structures that hold everything together and at the same time constantly move, change everything.

Fundamental Dimension of Time

All this implies the phenomenon ‘time’ as a basic category of all reality. Without time, there is also no ‘truth’…

[1] Specialists in brain research will of course raise their hand right away, and will want to say that they can indeed ‘look into the head’ by now, but let’s wait and see what this ‘looking into the head’ entails.

[2] If we assume for the number of stars in our home galaxy, the Milky Way, with an estimated 100 – 400 billion stars that there are 200 billion, then our body system would correspond to the scope of 700 galaxies in the format of the Milky Way, one cell for one star.

[3] Various disciplines of natural sciences, especially certainly evolutionary biology, have illuminated many aspects of this mega-wonder partially over the last approx. 150 years. One can marvel at the physical view of our universe, but compared to the super-galaxies of life on Planet Earth, the physical universe seems downright ‘boring’… Don’t worry: ultimately, both are interconnected: one explains the other…”

Telling Stories

Fragments of Everyday Life—Without Context

We constantly talk about something: the food, the weather, the traffic, shopping prices, daily news, politics, the boss, colleagues, sports events, music, … mostly, these are ‘fragments’ from the larger whole that we call ‘everyday life’. People in one of the many crisis regions on this planet, especially those in natural disasters or even in war…, live concretely in a completely different world, a world of survival and death.

These fragments in the midst of life are concrete, concern us, but they do not tell a story by themselves about where they come from (bombs, rain, heat,…), why they occur, how they are connected with other fragments. The rain that pours down is a single event at a specific place at a specific time. The bridge that must be closed because it is too old does not reveal from itself why this particular bridge, why now, why couldn’t this be ‘foreseen’? The people who are ‘too many’ in a country or also ‘too few’: Why is that? Could this have been foreseen? What can we do? What should we do?

The stream of individual events hits us, more or less powerfully, perhaps even simply as ‘noise’: we are so accustomed to it that we no longer even perceive certain events. But these events as such do not tell a ‘story about themselves’; they just happen, seemingly irresistibly; some say ‘It’s fate’.

Need for Meaning

It is notable that we humans still try to give the whole a ‘meaning’, to seek an ‘explanation’ for why things are the way they are. And everyday life shows that we have a lot of ‘imagination’ concerning possible ‘connections’ or ’causes’. Looking back into the past, we often smile at the various attempts at explanation by our ancestors: as long as nothing was known about the details of our bodies and about life in general, any story was possible. In our time, with science established for about 150 years, there are still many millions of people (possibly billions?) who know nothing about science and are willing to believe almost any story just because another person tells this story convincingly.

Liberation from the Moment through Words

Because of this ability, with the ‘power of imagination’ to pack things one experiences into a ‘story’ that suggests ‘possible connections’, through which events gain a ‘conceptual sense’, a person can try to ‘liberate’ themselves from the apparent ‘absoluteness of the moment’ in a certain way: an event that can be placed into a ‘context’ loses its ‘absoluteness’. Just by this kind of narrative, the experiencing person gains a bit of ‘power’: in narrating a connection, the narrator can make the experience ‘a matter’ over which they can ‘dispose’ as they see fit. This ‘power through the word’ can alleviate the ‘fear’ that an event can trigger. This has permeated the history of humanity from the beginning, as far as archaeological evidence allows.

Perhaps it is not wrong to first identify humans not as ‘hunters and gatherers’ or as ‘farmers’ but as ‘those who tell stories’.

[1] Such a magic word in Greek philosophy was the concept of ‘breath’ (Greek “pneuma”). The breath not only characterized the individually living but was also generalized to a life principle of everything that connected both body, soul, and spirit as well as permeated the entire universe. In the light of today’s knowledge, this ‘explanation’ could no longer be told, but about 2300 years ago, this belief was a certain ‘intellectual standard’ among all intellectuals, the prevailing ‘worldview’; it was ‘believed’. Anyone who thought differently was outside this ‘language game’.

Organization of an Order

Thinking Creates Relationships

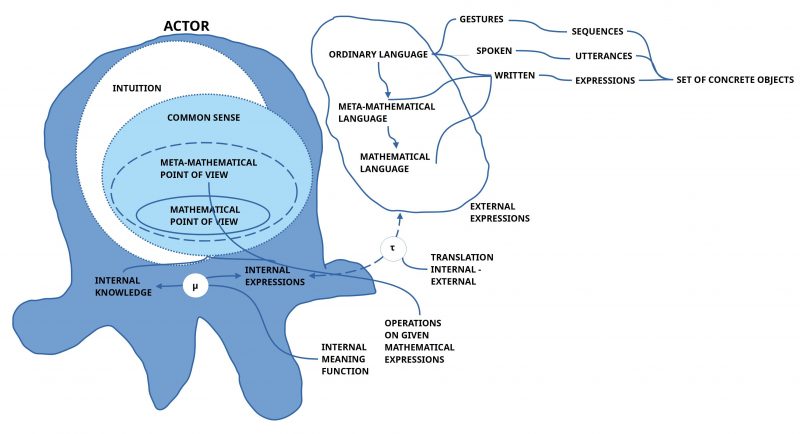

As soon as one can ‘name’ individual events, things, processes, properties of things, and more through ‘language’, it is evident that humans have the ability to not only ‘name’ using language but to embed the ‘named’ through ‘arrangement of words in linguistic expression’ into ‘conceived relationships’, thereby connecting the individually named items not in isolation but in thought with others. This fundamental human ability to ‘think relationships in one’s mind’, which cannot be ‘seen’ but can indeed be ‘thought’ [1], is of course not limited to single events or a single relationship. Ultimately, we humans can make ‘everything’ a subject, and we can ‘think’ any ‘possible relationship’ in our minds; there are no fundamental restrictions here.

Stories as a Natural Force

Not only history is full of examples, but also our present day. Today, despite the incredible successes of modern science, almost universally, the wildest stories with ‘purely thought relationships’ are being told and immediately believed through all channels worldwide, which should give us pause. Our fundamental characteristic, that we can tell stories to break the absoluteness of the moment, obviously has the character of a ‘natural force’, deeply rooted within us, that we cannot ‘eradicate’; we might be able to ‘tame’ it, perhaps ‘cultivate’ it, but we cannot stop it. It is an ‘elemental characteristic’ of our thinking, that is: of our brain in the body.

Thought and Verified

The experience that we, the storytellers, can name events and arrange them into relationships—and ultimately without limit—may indeed lead to chaos if the narrated network of relationships is ultimately ‘purely thought’, without any real reference to the ‘real world around us’, but it is also our greatest asset. With it, humans can not only fundamentally free themselves from the apparent absoluteness of the present, but we can also create starting points with the telling of stories, ‘initially just thought relationships’, which we can then concretely ‘verify’ in our everyday lives.

A System of Order

When someone randomly sees another person who looks very different from what they are used to, all sorts of ‘assumptions’ automatically form in each person about what kind of person this might be. If one stops at these assumptions, these wild guesses can ‘populate the head’ and the ‘world in the head’ gets populated with ‘potentially evil people’; eventually, they might simply become ‘evil’. However, if one makes contact with the other, they might find that the person is actually nice, interesting, funny, or the like. The ‘assumptions in the head’ then transform into ‘concrete experiences’ that differ from what was initially thought. ‘Assumptions’ combined with ‘verification’ can thus lead to the formation of ‘reality-near ideas of relationships’. This gives a person the chance to transform their ‘spontaneous network of thought relationships’, which can be wrong—and usually are—into a ‘verified network of relationships’. Since ultimately the thought relationships as a network provide us with a ‘system of order’ in which everyday things are embedded, it appears desirable to work with as many ‘verified thought relationships’ as possible.

[1] The breath of the person opposite me, which for the Greeks connected my counterpart with the life force of the universe, which in turn is also connected with the spirit and the soul…

Hypotheses and Science

Challenge: Methodically Organized Guessing

The ability to think of possible relationships, and to articulate them through language, is innate [1], but the ‘use’ of this ability in everyday life, for example, to match thought relationships with the reality of everyday life, this ‘matching’/’verifying’ is not innate. We can do it, but we don’t have to. Therefore, it is interesting to realize that since the first appearance of Homo sapiens on this planet [2], 99.95% of the time has passed until the establishment of organized modern science about 150 years ago. This can be seen as an indication that the transition from ‘free guessing’ to ‘methodically organized systematic guessing’ must have been anything but easy. And if today still a large part of people—despite schooling and even higher education—[3] tend to lean towards ‘free guessing’ and struggle with organized verification, then there seems to be a not easy threshold that a person must overcome—and must continually overcome—to transition from ‘free’ to ‘methodically organized’ guessing.[4]

Starting Point for Science

The transition from everyday thinking to ‘scientific thinking’ is fluid. The generation of ‘thought relationships’ in conjunction with language, due to our ability of creativity/imagination, is ultimately also the starting point of science. While in everyday thinking we tend to spontaneously and pragmatically ‘verify’ ‘spontaneously thought relationships’, ‘science’ attempts to organize such verifications ‘systematically’ to then accept such ‘positively verified guesses’ as ’empirically verified guesses’ until proven otherwise as ‘conditionally true’. Instead of ‘guesses’, science likes to speak of ‘hypotheses’ or ‘working hypotheses’, but they remain ‘guesses’ through the power of our thinking and through the power of our imagination.[5]

[1] This means that the genetic information underlying the development of our bodies is designed so that our body with its brain is constructed during the growth phase in such a way that we have precisely this ability to ‘think of relationships’. It is interesting again to ask how it is possible that from a single cell about 13 trillion body cells (the approximately 100 trillion bacteria in the gut come ‘from outside’) can develop in such a way that they create the ‘impression of a human’ that we know.

[2] According to current knowledge, about 300,000 years ago in East Africa and North Africa, from where Homo sapiens then explored and conquered the entire world (there were still remnants of other human forms that had been there longer).

[3] I am not aware of representative empirical studies on how many people in a population tend to do this.

[4] Considering that we humans as the life form Homo sapiens only appeared on this planet after about 3.8 billion years, the 300,000 years of Homo sapiens make up roughly 0.008% of the total time since there has been life on planet Earth. Thus, not only are we as Homo sapiens a very late ‘product’ of the life process, but the ability to ‘systematically verify hypotheses’ also appears ‘very late’ in our Homo sapiens life process. Viewed across the entire life span, this ability seems to be extremely valuable, which is indeed true considering the incredible insights we as Homo sapiens have been able to gain with this form of thinking. The question is how we deal with this knowledge. This behavior of using systematically verified knowledge is not innate too.

[5] The ability of ‘imagination’ is not the opposite of ‘knowledge’, but is something completely different. ‘Imagination’ is a trait that ‘shows’ itself the moment we start to think, perhaps even in the fact ‘that’ we think at all. Since we can in principle think about ‘everything’ that is ‘accessible’ to our thinking, imagination is a factor that helps to ‘select’ what we think. In this respect, imagination is pre-posed to thinking.