eJournal: uffmm.org, ISSN 2567-6458, Aug 19-20, 2021

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

SCOPE

In the uffmm review section the different papers and books are discussed from the point of view of the oksimo paradigm. [2] Here the author reads the book “Logic. The Theory Of Inquiry” by John Dewey, 1938. [1]

Part I – Chapter I

THE PROBLEM OF LOGICAL SUBJECT-MATTER

In this chapter Dewey tries to characterize the subject-matter of logic. From the year 1938 backwards one can look into a long history of thoughts with at least 2500 years dealing in one or another sense with what has been called ‘logic’. His rough judgment is that the participants of the logic language game “proximate subject-matter of logic” seem to be widely in agreement what it is, but in the case of the “ultimate subject-matter of logic” language game there seem to exist different or even conflicting opinions.(cf. p.8)

Logic as a philosophic theory

Dewey illustrates the variety of views about the ultimate subject-matter of logic by citing several different positions.(cf. p.10) Having done this Dewey puts all these views together into a kind of a ‘meta-view’ stating that logic “is a branch of philosophic theory and therefore can express different philosophies.”(p.10) But exercising philosophy ” itself must satisfy logical requirements.”(p.10)

And in general he thinks that “any statement that logic is so-and-so, can … be offered only as a hypothesis and an indication of a position to be developed.”(p.11)

Thus we see here that Dewey declares the ultimate logical subject-matter grounded in some philosophical perspective which should be able “to order and account for what has been called the proximate subject-matter.”(p.11) But the philosophical theory “must possess the property of verifiable existence in some domain, no matter how hypothetical it is in reference to the field in which it is proposed to apply it.”(p.11) This is an interesting point because this implies the question in which sense a philosophical foundation of logic can offer a verifiable existence.

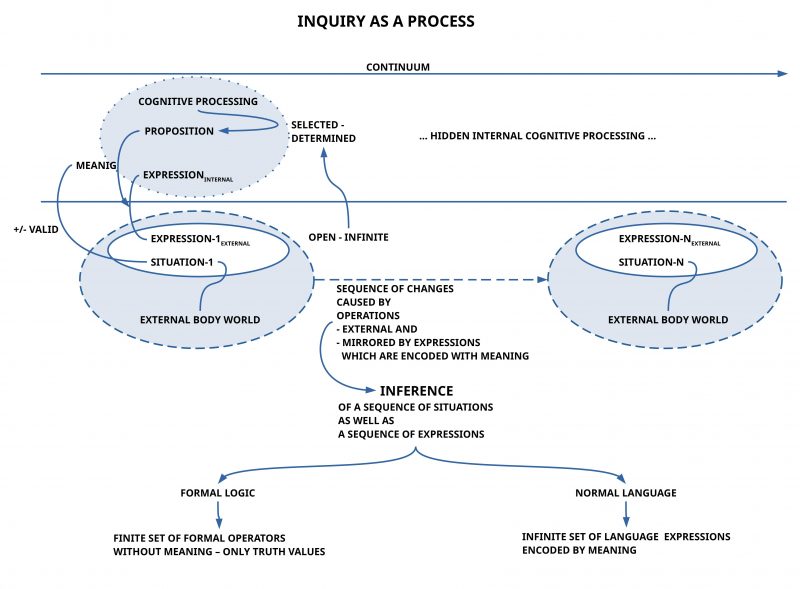

Inquiry

Dewey gives some hint for a possible answer by stating “that all logical forms … arise within the operation of inquiry and are concerned with control of inquiry so that it may yield warranted assertions.”(p.11) While the inquiry as a process is real, the emergence of logical forms has to be located in the different kinds of interactions between the researchers and some additional environment in the process. Here should some verifiable reality be involved which is reflected in accompanying language expressions used by the researchers for communication. This implies further that the used language expressions — which can even talk about other language expressions — are associated with propositions which can be shown to be valid.[4]

And — with some interesting similarity with the modern concept of ‘diversity’ — he claims that in avoidance of any kind of dogmatism “any hypothesis, no matter how unfamiliar, should have a fair chance and be judged by its results.”(p.12)

While Dewey is quite clear to use the concept of inquiry as a process leading to some results which are depending from the starting point and the realized processes, he mentions additionally concepts like ‘methods’, ‘norms’, ‘instrumentalities’, and ‘procedures’, but these concepts are rather fuzzy. (cf. p.14f)

Warranted assertibility

Part of an inquiry are the individual actors which have psychological states like ‘doubt’ or ‘belief’ or ‘understanding’ (knowledge).(p.15) But from these concepts follows nothing about needed logical forms or rules.(cf.p.16f) Instead Dewey repeats his requirement with the words “In scientific inquiry, the criterion of what is taken to be settled, or to be knowledge, is being so settled that it is available as a resource in further inquiry; not being settled in such a way as not to be subject to revision in further inquiry.”(p.17) And therefore, instead of using fuzzy concepts like (subjective) ‘doubt’, ‘believe’ or ‘knowledge’, prefers to use the concept “warranted assertibility”. This says not only, that you can assert something, but that you can assert it also with ‘warranty’ based on the known process which has led to this result.(cf. p.10)

Introducing rationality

At this point the story takes a first ‘new turn’ because Dewey introduces now a first characterization of the concept ‘rationality’ (which is for him synonymous with ‘reasonableness’). While the basic terms of the descriptions in an inquiry process are at least partially descriptive (empirical) expressions, they are not completely “devoid of rational standing”.(cf. p.17) Furthermore the classification of final situations in an inquiry as ‘results’ which can be understood as ‘confirmations’ of initial assumptions, questions or problems, is only given in relations talking about the whole process and thereby they are talking about matters which are not rooted in limited descriptive facts only. Or, as Dewey states it, “relations which exist between means (methods) employed and conclusions attained as their consequence.”(p.17) Therefore the following practical principle is valid: “It is reasonable to search for and select the means that will, with the maximum probability, yield the consequences which are intended.”(p.18) And: “Hence,… the descriptive statement of methods that achieve progressively stable beliefs, or warranted assertibility, is also a rational statement in case the relation between them as means and assertibility as consequence is ascertained.”(p.18)

Suggested framework for ‘rationality’

Although Dewey does not exactly define the format of relations between selected means and successful consequences it seems ‘intuitively’ clear that the researchers have to have some ‘idea’ of such a relation which serves then as a new ‘ground for abstract meaning’ in their ‘thinking’. Within the oksimo paradigm [2] one could describe the problem at hand as follows:

- The researchers participating in an inquiry process have perceptions of the process.

- They have associated cognitive processing as well as language processing, where both are bi-directional mapped into each other, but not 1-to-1.

- They can describe the individual properties, objects, actors, actions etc. which are part of the process in a timely order.

- They can with their cognitive processing build more abstract concepts based on these primary concepts.

- They can encode these more abstract cognitive structures and processes in propositions (and expressions) which correspond to these more abstract cognitive entities.

- They can construct rule-like cognitive structures (within the oksimo paradigm called ‘change rules‘) with corresponding propositions (and expressions).

- They can evaluate those change rules whether they describe ‘successful‘ consequences.

- Change rules with successful consequences can become building blocks for those rules, which can be used for inferences/ deductions.

Thus one can look to the formal aspect of formal relations which can be generated by an inference mechanism, but such a formal inference must not necessarily yield results which are empirically sound. Whether this will be the case is a job on its own dealing with the encoded meaning of the inferred expressions and the outcome of the inquiry.(cf. p.19,21)

Limitations of formal logic

From this follows that the concrete logical operators as part of the inference machinery have to be qualified by their role within the more general relation between goals, means and success. The standard operators of modern formal logic are only a few and they are designed for a domain where you have a meaning space with only two objects: ‘being true’, being false’. In the real world of everyday experience we have a nearly infinite space of meanings. To describe this everyday large meaning space the standard logic of today is too limited. Normal language teaches us, how we can generate as many operators as we need only by using normal language. Inferring operators directly from normal language is not only more powerful but at the same time much, much easier to apply.[2]

Inquiry process – re-formulated

Let us fix a first hypothesis here. The ideas of Dewey can be re-framed with the following assumptions:

- By doing an inquiry process with some problem (question,…) at the start and proceeding with clearly defined actions, we can reach final states which either are classified as being a positive answer (success) of the problem of the beginning or not.

- If there exists a repeatable inquiry process with positive answers the whole process can be understood as a new ‘recipe’ (= complex operation, procedure, complex method, complex rule,law, …) how to get positive answers for certain kinds of questions.

- If a recipe is available from preceding experiments one can use this recipe to ‘plan’ a new process to reach a certain ‘result’ (‘outcome’, ‘answer’, …).

- The amount of failures as part of the whole number of trials in applying a recipe can be used to get some measure for the probability and quality of the recipe.

- The description of a recipe needs a meta-level of ‘looking at’ the process. This meta-level description is sound (‘valid’) by the interaction with reality but as such the description includes some abstraction which enables a minimal rationality.

Habit

At this point Dewey introduces another term ‘habit’ which is not really very clear and which not really does explain more, but — for whatever reason — he introduces such a term.(cf. p.21f)

The intuition behind the term ‘habit’ is that independent of the language dimension there exists the real process driven by real actors doing real actions. It is further — tacitly — assumed that these real actors have some ‘internal processing’ which is ‘causing’ the observable actions. If these observable actions can be understood/ interpreted as an ‘inquiry process’ leading to some ‘positive answers’ then Dewey calls the underlying processes all together a ‘habit’: “Any habit is a way or manner of action, not a particular act or deed. “(p.20) If one observes such a real process one can describe it with language expressions; then it gets the format of a ‘rule’, a principle’ or a ‘law’.(cf. p.20)

If one would throw away the concept ‘habit’, nothing would be missing. Whichever internal processes are assumed, a description of these will be bound to its observability and will depend of some minimal language mechanisms. These must be explained. Everything beyond these is not necessary to explain rational behavior.[5]

At the end of chapter I Dewey points to some additional aspects in the context of logic. One aspect is the progressive character of logic as discipline in the course of history.(cf. p.22)[6]

Operational

Another aspect is introduced by his statement “The subject-matter of logic is determined operationally.”(p.22) And he characterizes the meaning of the term ‘operational’ as representing the “conditions by which subject-matter is (1) rendered fit to serve as means and (2) actually functions as such means in effecting the objective transformation which is the end of the inquiry.”(p.22) Thus, again, the concept of inquiry is the general framework organizing means to get to a successful end. This inquiry has an empirical material (or ‘existential‘) basis which additionally can be described symbolically. The material basis can be characterized by parts of it called ‘means’ which are necessary to enable objective transformations leading to the end of the inquiry.(cf. p.22f)

One has to consider at this point that the fact of the existential (empirical) basis of every inquiry process should not mislead to the view that this can work without a symbolic dimension! Besides extremely simple processes every process needs for its coordination between different brains a symbolic communication which has to use certain expressions of a language. Thus the cognitive concepts of the empirical means and the followed rules can only get ‘fixed’ and made ‘clear’ with the usage of accompanying symbolic expressions.

Postulational logic

Another aspect mentioned by Dewey is given by the statement: “Logical forms are postulational.“(p.24) Embedded in the framework of an inquiry Dewey identifies requirements (demands, postulates, …) in the beginning of the inquiry which have to be fulfilled through the inquiry process. And Dewey sees such requirements as part of the inquiry process itself.(cf. p.24f) If during such an inquiry process some kinds of logical postulates will be used they have no right on their own independent of the real process! They can only be used as long as they are in agreement with the real process. With the words of Dewey: “A postulate is thus neither arbitrary nor externally a priori. It is not the former because it issues from the relation of means to the end to be reached. It is not the latter, because it is not imposed upon inquiry from without, but is an acknowledgement of that to which the undertaking of inquiry commits us.”(p.26) .

Logic naturalistic

Dewey comments further on the topic that “Logic is a naturalistic theory.“(p.27 In some sense this is trivial because humans are biological systems and therefore every process is a biological (natural) process, also logical thinking as part of it.

Logic is social

Dewey mentions further that “Logic is a social discipline.“(p.27) This follows from the fact that “man is naturally a being that lives in association with others in communities possessing language, and therefore enjoying a transmitted culture. Inquiry is a mode of activity that is socially conditioned and that has cultural consequences.”(p.27) And therefore: “Any theory of logic has to take some stand on the question whether symbols are ready-made clothing for meanings that subsist independently, or whether they are necessary conditions for the existence of meanings — in terms often used, whether language is the dress of ‘thought’ or is something without which ‘thought’ cannot be.” (27f) This can be put also in the following general formula by Dewey: “…in every interaction that involves intelligent direction, the physical environment is part of a more inclusive social or cultural environment.” (p.28) The central means of culture is Language, which “is the medium in which culture exists and through which it is transmitted. Phenomena that are not recorded cannot be even discussed. Language is the record that perpetuates occurrences and renders them amenable to public consideration. On the other hand, ideas or meanings that exist only in symbols that are not communicable are fantastic beyond imagination”.(p.28)

Autonomous logic

The final aspect about logic which is mentioned by Dewey looks to the position which states that “Logic is autonomous“.(p.29) Although the position of the autonomy of logic — in various varieties — is very common in history, but Dewey argues against this position. The main point is — as already discussed before — that the open framework of an inquiry gives the main point of reference and logic must fit to this framework.[7]

SOME DISCUSSION

For a discussion of these ideas of Dewey see the next uocoming post.

COMMENTS

[1] John Dewey, Logic. The Theory Of Inquiry, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1938 (see: https://archive.org/details/JohnDeweyLogicTheTheoryOfInquiry with several formats; I am using the kindle (= mobi) format: https://archive.org/download/JohnDeweyLogicTheTheoryOfInquiry/%5BJohn_Dewey%5D_Logic_-_The_Theory_of_Inquiry.mobi . This is for the direct work with a text very convenient. Additionally I am using a free reader ‘foliate’ under ubuntu 20.04: https://github.com/johnfactotum/foliate/releases/). The page numbers in the text of the review — like (p.13) — are the page numbers of the ebook as indicated in the ebook-reader foliate.(There exists no kindle-version for linux (although amazon couldn’t work without linux servers!))

[2] Gerd Doeben-Henisch, 2021, uffmm.org, THE OKSIMO PARADIGM

An Introduction (Version 2), https://www.uffmm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/oksimo-v1-part1-v2.pdf

[3] The new oksimo paradigm does exactly this. See oksimo.org

[4] For the conceptual framework for the term ‘proposition’ see the preceding part 2, where the author describes the basic epistemological assumptions of the oksimo paradigm.

[5] Clearly it is possible and desirable to extend our knowledge about the internal processing of human persons. This is mainly the subject-matter of biology, brain research, and physiology. Other disciplines are close by like Psychology, ethology, linguistics, phonetics etc. The main problem with all these disciplines is that they are methodologically disconnected: a really integrated theory is not yet possible and not in existence. Examples of integrations like Neuro-Psychology are far from what they should be.

[6] A very good overview about the development of logic can be found in the book The Development of Logic by William and Martha Kneale. First published 1962 with many successive corrected reprints by Clarendon Press, Oxford (and other cities.)

[7] Today we have the general problem that the concept of formal logic has developed the concept of logical inference in so many divergent directions that it is not a simple problem to evaluate all these different ‘kinds of logic’.

MEDIA

This is another unplugged recording dealing with the main idea of Dewey in chapter I: what is logic and how relates logic to a scientific inquiry.