Integrating Engineering and the Human Factor (info@uffmm.org)

eJournal uffmm.org ISSN 2567-6458, Nov 8, 2020

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

CONTEXT

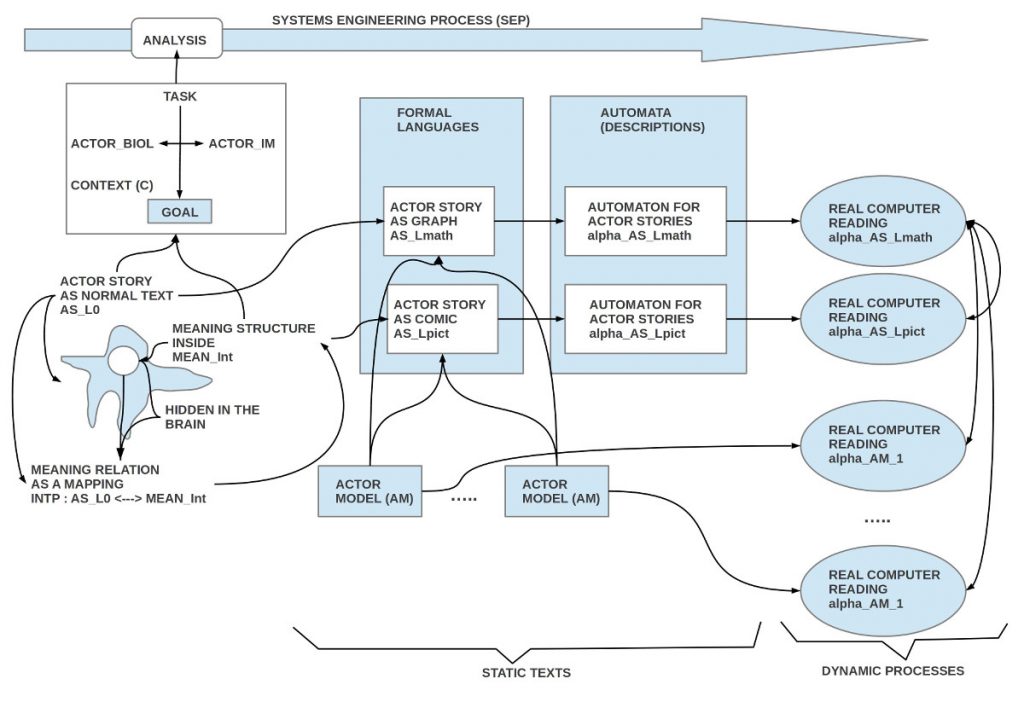

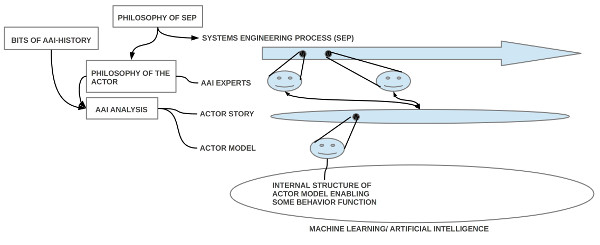

As described in the uffmm eJournal the wider context of this software project is a generative theory of cultural anthropology [GCA] which is an extension of the engineering theory called Distributed Actor-Actor Interaction [DAAI]. In the section Case Studies of the uffmm eJournal there is also a section about Python co-learning – mainly

dealing with python programming – and a section about a web-server with

Dragon. This document is part of the Case Studies section.

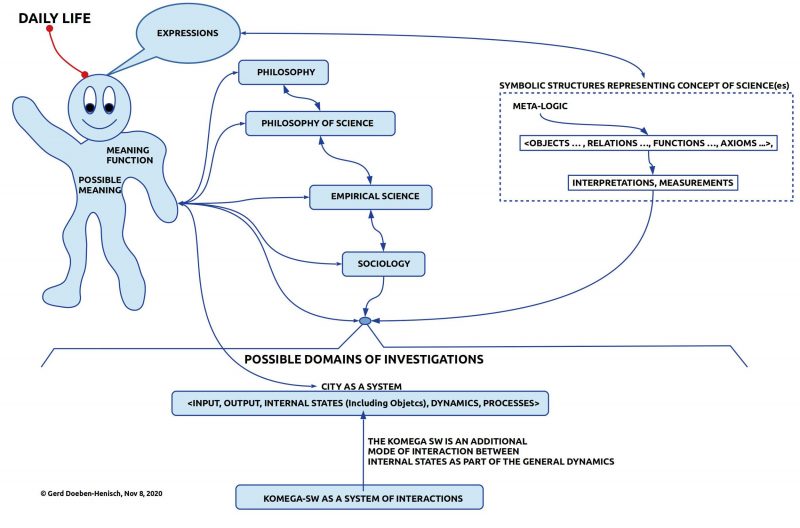

DAILY LIFE

In daily life we experience today a multitude of perspectives in all areas. While our bodies are embedded in real world scenarios our minds are filled up with perceptions, emotions, ideas, memories of all kinds. What links us to each other is language. Language gives us the power to overcome the isolation of our individual brains located in individual bodies. And by this, our language, we can distribute and share the inner states of our brains, pictures of life as we see it. And it is this open web of expressions which spreads to the air, to the newspapers and books, to the data bases in which the different views of the world are manifested.

SORTING IDEAS SCIENTIFICALLY

While our bodies touching reality outside the bodies, our brains are organizing different kinds of order, finally expressed — only some part of it — in expressions of some language. While our daily talk is following mostly automatically some naive patterns of ordering does empirical science try to order the expressions more consciously following some self-defined rules called methods, called scientific procedures to enable transparency, repeatability, decidability of the hypothesized truth of is symbolic structures.

But because empirical science wants to be rational by being transparent, repeatable, measurable, there must exist an open discourse which is dealing with science as an object: what are the ingredients of science? Under which conditions can science work? What does it mean to ‘measure’ something? And other questions like these.

PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

That discipline which is responsible for such a discourse about science is not science itself but another instance of thinking and speaking which is called Philosophy of Science. Philosophy of science deals with all aspects of science from the outside of science.

PHILOSOPHY

Philosophy of Science dealing with empirical sciences as an object has a special focus and it can be reflected too from another point of view dealing with Philosophy of Science as an object. This relationship reflects a general structure of human thinking: every time we have some object of our thinking we are practicing a different point of view talking about the actual object. While everyday thinking leads us directly to Philosophy as our active point of view an object like empirical science does allow an intermediate point of view called Philosophy of Science leading then to Philosophy again.

Philosophy is our last point of reflection. If we want to reflect the conditions of our philosophical thinking than our thinking along with the used language tries to turn back on itself but this is difficult. The whole history of Philosophy shows this unending endeavor as a consciousness trying to explain itself by being inside itself. Famous examples of this kind of thinking are e.g. Descartes, Kant, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, and Husserl.

These examples show there exists no real way out.

PHILOSOPHY ENHANCED BY EMPIRICAL SCIENCES ? !

At a first glance it seems contradictory that Philosophy and Empirical Sciences could work ‘hand in hand’. But history has shown us, that this is to a certain extend possible; perhaps it is a major break through for the philosophical understanding of the world, especially also of men themselves.

Modern empirical sciences like Biology and Evolutionary Biology in cooperation with many other empirical disciplines have shown us, that the actual biological systems — including homo sapiens — are products of a so-called evolutionary process. And supported by modern empirical disciplines like Ethology, Psychology, Physiology, and Brain Sciences we could gain some first knowledge how our body works, how our brain, how our observable behavior is connected to this body and its brain.

While Philosopher like Kant or Hegel could investigate their own thinking only from the inside of their consciousness, the modern empirical sciences can investigate the human thinking from the outside. But until now there is a gap: We have no elaborated theory about the relationship between the inside of the consciousness and the outside knowledge about body and brain.

Thus what we need is a hybrid theory mapping the inside to the outside and revers. There are some first approaches headed under labels like Neuro-Psychology or Neuro-Phenomenology, but these are not yet completely clarified in their methodology in their relationship to Philosophy.

If one can describe to some extend the Phenomena of the consciousness from the inside as well as the working of the brain translated to its behavioral properties, then one can start first mappings like those, which have been used in this blog to establish the theory for the komega software.

SOCIOLOGY

Sociology is only one empirical discipline between many others. Although the theory of this blog is using many disciplines simultaneously Sociology is of special interest because it is that kind of empirical disciplines which is explicitly dealing with human societies with subsystems called cities.

The komega software which we are developing is understood here as enabling a system of interactions as part of a city understood as a system. If we understand Sociology as an empirical science according to some standard view of empirical science then it is possible to describe a city as an input-output system whose dynamics can become influenced by this komega software if citizens are using this software as part of their behavior.

STANDARD VIEW OF EMPIRICAL SCIENCE

Without some kind of a Standard View of Empirical Science it is not possible to design a discipline — e.g. Sociology — as an empirical discipline. Although it seems that everybody thinks that we have such a ‘Standard View of Empirical Science’, in the real world of today one must state that we do not have such a view. In the 80ties of the20th century it looked for some time as if we have it, but if you start searching the papers, books and schools today You will perceive a very fuzzy field called Philosophy of Science and within the so-called empirical sciences you will not found any coherent documented view of a ‘Standard View of Empirical Science’.

Because it is difficult to see how a process can look like which enables such a ‘Standard View of Empirical Science’ again, we will try to document the own assumptions for our theory as good as possible. Inevitably this will mostly have the character of only a ‘fragment’, an ‘incomplete outline’. Perhaps there will again be a time where sciences is back to have a commonly accepted view how science should look like to be called empirical science.