(Last change: Nov 1, 2023)

CONTEXT

This text belongs to the overall theme REVIEWS.

In the last months I was engaged with the topic of text-generating algorithms and the possible impact for a scientific discourse (some first notices to this discussion you can find here (https://www.uffmm.org/2023/08/24/homo-sapiens-empirical-and-sustained-empirical-theories-emotions-and-machines-a-sketch/)). In this context it is important to clarify the role and structure of human actors as well as the concept of Intelligence. Meanwhile I have abandoned the word Intelligence completely because the inflationary use in today mainstream pulverises any meaning. Even in one discipline — like psychology — you can find many different concepts. In this context I have read the book of Stanovich et.al to have a prominent example of using the concept of intelligence, there combined with the concept of rationality, which is no less vague.

Introduction

The book “The Rationality Quotient” from 2016 represents not the beginning of a discourse but is a kind of summary of a long lasting discourse with many publications before. This makes this book interesting, but also difficult to read in the beginning, because the book is using nearly on every page theoretical terms, which are assumed to be known to the reader and cites other publications without giving sufficient explanations why exactly these cited publications are important. This is no argument against this book but sheds some light on the reader, who has to learn a lot to understand the text.

A text with the character of summing up its subject is good, because it has a confirmed meaning about the subject which enables a kind of clarity which is typical for that state of elaborated point of view.

In the following review it is not the goal to give a complete account of every detail of this book but only to present the main thesis and then to analyze the used methods and the applied epistemological framework.

Main Thesis of the Book

The reviewing starts with the basic assumptions and the main thesis.

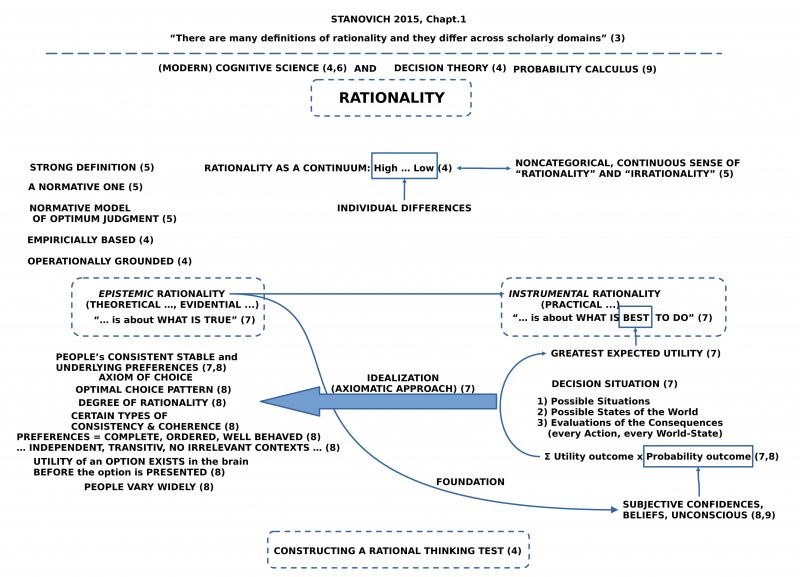

FIGURE 1 : The beginning. Note: the number ‘2015’ has to be corrected to ‘2016’.

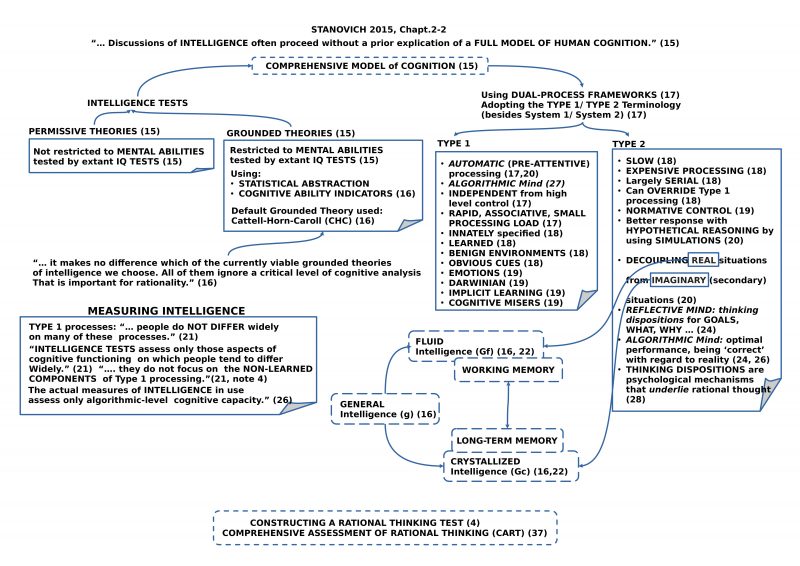

FIGURE 2 : First outline of cognition. Note: the number ‘2015’ has to be corrected to ‘2016’.

As mentioned in the introduction you will in the book not find a real overview about the history of psychological research dealing with the concept of Intelligence and also no overview about the historical discourse to the concept of Rationality, whereby the last concept has also a rich tradition in Philosophy. Thus, somehow you have to know it.

There are some clear warnings with regard to the fuzziness of the concept rationality (p.3) as well as to the concept of intelligence (p.15). From a point of view of Philosophy of Science it could be interesting to know what the circumstances are which are causing such a fuzziness, but this is not a topic of the book. The book talks within its own selected conceptual paradigm. Being in the dilemma, of what kind of intelligence paradigm one wants to use, the book has decided to work with the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CTC) paradigm, which some call a theory. [1]

Directly from the beginning it is explained that the discussion of Intelligence is missing a clear explanation of the full human model of cognition (p.15) and that intelligence tests therefore are mostly measuring only parts of human cognitive functions. (p.21)

Thus let us have a more detailed look to the scenario.

[1] For a first look to the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cattell%E2%80%93Horn%E2%80%93Carroll_theory, a first overview.

Which point of View?

The book starts with a first characterization of the concept of Rationality within a point of view which is not really clear. From different remarks one gets some hints to modern Cognitive Science (4,6), to Decision Theory (4) and Probability Calculus (9), but a clear description is missing.

And it is declared right from the beginning, that the main aim of the book is the Construction of a rational Thinking Test (4), because for the authors the used Intelligence Tests — later reduced to the Carroll-Horn-Carroll (CHC) type of intelligence test (16) — are too narrow in what they are measuring (15, 16, 21).

Related to the term Rationality the book characterizes some requirements which the term rationality should fulfill (e.g. ‘Rationality as a continuum’ (4), ’empirically based’ (4), ‘operationally grounded’ (4), a ‘strong definition’ (5), a ‘normative one’ (5), ‘normative model of optimum judgment’ (5)), but it is more or less open, what these requirements imply and what tacit assumptions have to be fulfilled, that this will work.

The two requirements ’empirically based’ as well as ‘operationally grounded’ point in the direction of an tacitly assumed concept of an empirical theory, but exactly this concept — and especially in association with the term cognitive science — isn’t really clear today.

Because the authors make in the next pages a lot of statements which claim to be serious, it seems to be important for the discussion in this review text to clarify the conditions of the ‘meaning of language expressions’ and of being classified as ‘being true’.

If we assume — tentatively — that the authors assume a scientific theory to be primarily a text whose expressions have a meaning which can transparently be associated with an empirical fact and if this is the case, then the expression will be understood as being grounded and classified as true, then we have characterized a normal text which can be used in everyday live for the communication of meanings which can become demonstrated as being true.

Is there a difference between such a ‘normal text’ and a ‘scientific theory’? And, especially here, where the context should be a scientific theory within the discipline of cognitive science: what distinguishes a normal text from a ‘scientific theory within cognitive science’?

Because the authors do not explain their conceptual framework called cognitive science we recur here to a most general characterization [2,3] which tells us, that cognitive science is not a single discipline but an interdisciplinary study which is taking from many different disciplines. It has not yet reached a state where all used methods and terms are embedded in one general coherent framework. Thus the relationship of the used conceptual frameworks is mostly fuzzy, unclear. From this follows directly, that the relationship of the different terms to each other — e.g. like ‘underlying preferences’ and ‘well ordered’ — is within such a blurred context rather unclear.

Even the simple characterization of an expression as ‘having an empirical meaning’ is unclear: what are the kinds of empirical subjects and the used terms? According to the list of involved disciplines the disciplines linguistics [4], psychology [5] or neuroscience [6] — besides others — are mentioned. But every of these disciplines is itself today a broad field of methods, not integrated, dealing with a multifaceted subject.

Using an Auxiliary Construction as a Minimal Point of Reference

Instead of becoming somehow paralyzed from these one-and-all characterizations of the individual disciplines one can try to step back and taking a look to basic assumptions about empirical perspectives.

If we take a group of Human Observers which shall investigate these subjects we could make the following assumptions:

- Empirical Linguistics is dealing with languages, spoken as well as written by human persons, within certain environments, and these can be observed as empirical entities.

- Empirical Psychology is dealing with the behavior of human persons (a kind of biological systems) within certain environments, and these can be observed.

- Empirical Neuroscience is dealing with the brain as part of a body which is located in some environment, and this all can be observed.

The empirical observations of certain kinds of empirical phenomena can be used to define more abstract concepts, relations, and processes. These more abstract concepts, relations, and processes have ‘as such’ no empirical meaning! They constitute a formal framework which has to become correlated with empirical facts to get some empirical meaning. As it is known from philosophy of science [7] the combination of empirical concepts within a formal framework of abstracts terms can enable ‘abstract meanings’ which by logical conclusions can produce statements which are — in the moment of stating them — not empirically true, because ‘real future’ has not yet happened. And on account of the ‘generality’ of abstract terms compared to the finiteness and concreteness of empirical facts it can happen, that the inferred statements never will become true. Therefore the mere usage of abstract terms within a text called scientific theory does not guarantee valid empirical statements.

And in general one has to state, that a coherent scientific theory including e.g. linguistics, psychology and neuroscience, is not yet in existence.

To speak of cognitive science as if this represents a clearly defined coherent discipline seems therefore to be misleading.

This raises questions about the project of a constructing a coherent rational thinking test (CART).

[2] See ‘cognitive science’ in wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_science

[3] See too ‘cognitive science’ in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cognitive-science/

[4] See ‘linguistics’ in wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistics

[5] See ‘psychology’ in wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychology

[6] See ‘neuroscience’ in wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroscience

[7] See ‘philosophy of science’ in wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_science

‘CART’ TEST FRAMEWORK – A Reconstruction from the point of View of Philosophy of Science

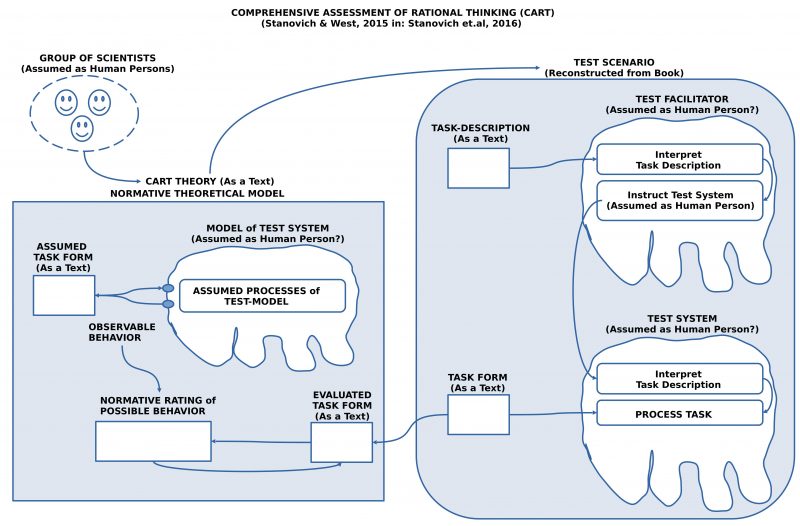

Before I will dig deeper into the theory I try to understand the intended outcome of this theory as some point of reference. The following figure 3 gives some hints.

FIGURE 3 : Outline of the Test Framework based on the Appendix in Stanovich et.al 2016. This Outline is a Reconstruction by the author of this review.

It seems to be important to distinguish at least three main parts of the whole scientific endeavor:

- The group of scientists which has decided to process a certain problem.

- The generated scientific theory as a text.

- The description of a CART Test, which describes a procedure, how the abstract terms of the theory can be associated with real facts.

From the group of scientists (Stanovich et al.) we know that they understand themselves as cognitive scientists (without having a clear characterization, what this means concretely).

The intended scientific theory as a text is here assumed to be realized in the book, which is here the subject of a review.

The description of a CART Test is here taken from the appendix of the book.

To understand the theory it is interesting to see, that in the real test the test system (assumed here as a human person) has to read (and hear?) a instruction, how to proceed with a task form, and then the test system (a human person) has to process the test form in the way it has understood the instructions and the test form as it is.

The result is a completed test form.

And it is then this completed test form which will be rated according to the assumed CART theory.

This complete paradigm raises a whole bunch of questions which to answer here in full is somehow out of range.

Mix-Up of Abstract Terms

Because the Test Scenario presupposes a CART theory and within this theory some kind of a model of intended test users it can be helpful to have a more closer look to this assumed CART model, which is located in a person.

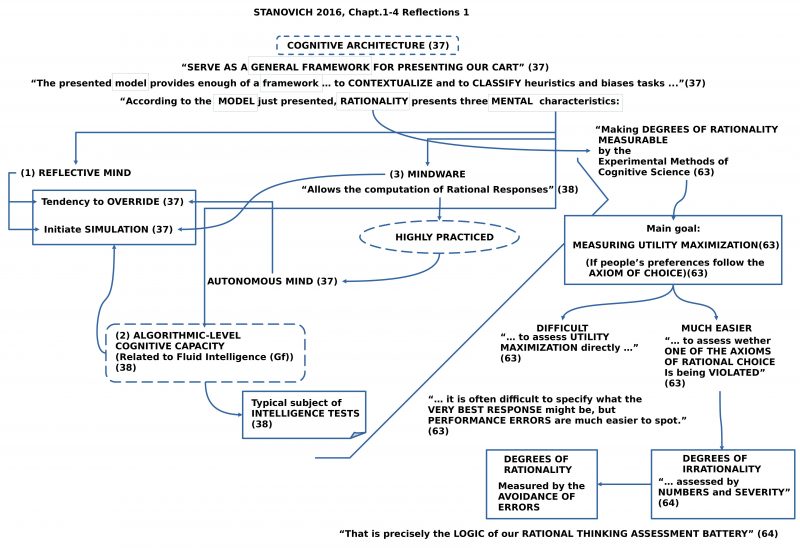

FIGURE 4 : General outline of the logic behind CART according to Stanovich et al. (2016).

The presented cognitive architecture shall present a framework for the CART (Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking), whereby this framework is including a model. The model is not only assumed to contextualize and classify heuristics and tasks, but it also presents Rationality in a way that one can deduce mental characteristics included in rationality.(cf. 37)

Because the term Rationality is not an individual empirical fact but an abstract term of a conceptual framework, this term has as such no meaning. The meaning of this abstract term has to be arranged by relations to other abstract terms which themselves are sufficiently related to concrete empirical statements. And these relations between abstract terms and empirical facts (represented as language expressions) have to be represented in a manner, that it is transparent how the the measured facts are related to the abstract terms.

Here Stanovich et al. is using another abstract term Mind, which is associated with characteristics called mental characteristics: Reflective mind, Algorithmic Level, and Mindware.

And then the text tells that Rationality is presenting mental characteristics. What does this mean? Is rationality different from the mind, who has some characteristics, which can be presented from rationality using somehow the mind, or is rationality nevertheless part of the mind and manifests themself in these mental characteristics? But what kind of the meaning could this be for an abstract term like rationality to be part of the mind? Without an explicit model associated with the term Mind which arranges the other abstract term Rationality within this model there exists no meaning which can be used here.

These considerations are the effect of a text, which uses different abstract terms in a way, which is rather unclear. In a scientific theory this should not be the case.

Measuring Degrees of Rationality

In the beginning of chapter 4 Stanovich et al. are looking back to chapter 1. Here they built up a chain of arguments which illustrate some general perspective (cf. 63):

- Rationality has degrees.

- These degrees of rationality can be measured.

- Measurement is realized by experimental methods of cognitive science.

- The measuring is based on the observable behavior of people.

- The observable behavior can manifest whether the individual actor (a human person) follows assumed preferences related to an assumed axiom of choice.

- Observable behavior which is classified as manifesting assumed internal preferences according to an assumed internal axiom of choice can show descriptive and procedural invariance.

- Based on these deduced descriptive and procedural invariance, it can be inferred further, that these actors are behaving as if they are maximizing utility.

- It is difficult to assess utility maximization directly.

- It is much easier to assess whether one of the axioms of rational choice is being violated.

These statements characterize the Logic of the CART according to Stanovich et al. (cf.64)

A major point in this argumentation is the assumption, that observable behavior is such, that one can deduce from the properties of this behavior those attributes/ properties, which point (i) to an internal model of an axiom of choice, (ii) to internal processes, which manifest the effects of this internal model, (iii) to certain characteristics of these internal processes which allow the deduction of the property of maximizing utility or not.

These are very strong assumptions.

If one takes further into account the explanations from the pages 7f about the required properties for an abstract term axiom of choice (cf. figure 1) then these assumptions appear to be very demanding.

Can it be possible to extract the necessary meaning out of observable behavior in a way, which is clear enough by empirical standards, that this behavior shows property A and not property B ?

As we know from the description of the CART in the appendix of the book (cf. figure 3) the real behavior assumed for an CART is the (i) reading (or hearing?) of an instruction communicated by ordinary English, and then (ii) a behavior deduced from the understanding of the instruction, which (iii) manifests themself in the reading of a form with a text and filling out this form in predefined positions in a required language.

This described procedure is quite common throughout psychology and similar disciplines. But it is well known, that the understanding of language instructions is very error-prone. Furthermore, the presentation of a task as a text is inevitably highly biased and additionally too very error-prone with regard to the understanding (this is a reason why in usability testing purely text-based tests are rather useless).

The point is, that the empirical basis is not given as a protocol of observations of language free behavior but of a behavior which is nearly completely embedded in the understanding and handling of texts. This points to the underlying processes of text understanding which are completely internal to the actor. There exists no prewired connection between the observable strings of signs constituting a text and the possible meaning which can be organized by the individual processes of text understanding.

Stopping Here

Having reached this point of reading and trying to understand I decided to stop here: to many questions on all levels of a scientific discourse and the relationships between main concepts and terms appear in the book of Stanovich et al. to be not clear enough. I feel therefore confirmed in my working hypothesis from the beginning, that the concept of intelligence today is far too vague, too ambiguous to contain any useful kernel of meaning any more. And concepts like Rationality, Mind (and many others) seem to do not better.

Chatting with chatGPT4

Since April 2023 I have started to check the ability of chatGPT4 to contribute to a philosophical and scientific discourse. The working hypothesis is, that chatGPT4 is good in summarizing the common concepts, which are used in public texts, but chatGPT is not able for critical evaluations, not for really new creative ideas and in no case for systematic analysis of used methods, used frameworks, their interrelations, their truth-conditons and much more, what it cannot. Nevertheless, it is a good ‘common sense check’. Until now I couldn’t learn anything new from these chats.

If you have read this review with all the details and open questions you will be perhaps a little bit disappointed about the answers from chatGPT4. But keep calm: it is a bit helpful.