Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Time: Febr 3, 2024 – Febr 3, 2024, 10:08 a.m. CET

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

TRANSLATION & COMMENTS: The following text is a translation from a German version into English. For the translation I am using the software deepL.com. For commenting on the whole text I am using @chatGPT4.

CONTEXT

This text belongs to the topic Philosophy (of Science).

If someone has already decided in his head that there is no problem, he won’t see a problem … and if you see a problem where there is none, you have little chance of being able to solve anything.

Written at the end of some letter…

To put it simply: we can be the solution if we are not the problem ourselves

PREFACE

The original – admittedly somewhat long – text entitled “MODERN PROPAGANDA – From a philosophical perspective. First reflections” started with the question of what actually constitutes the core of propaganda, and then ended up with the central insight that what is called ‘propaganda’ is only a special case of something much more general that dominates our thinking as humans: the world of narratives. This was followed by a relatively long philosophical analysis of the cognitive and emotional foundations of this phenomenon.

Since the central text on the role of narratives as part of the aforementioned larger text was a bit ‘invisible’ for many, here is a blog post that highlights this text again, and at the same time connects this text with an experiment in which the individual sections of the text are commented on by @chatGPT4.

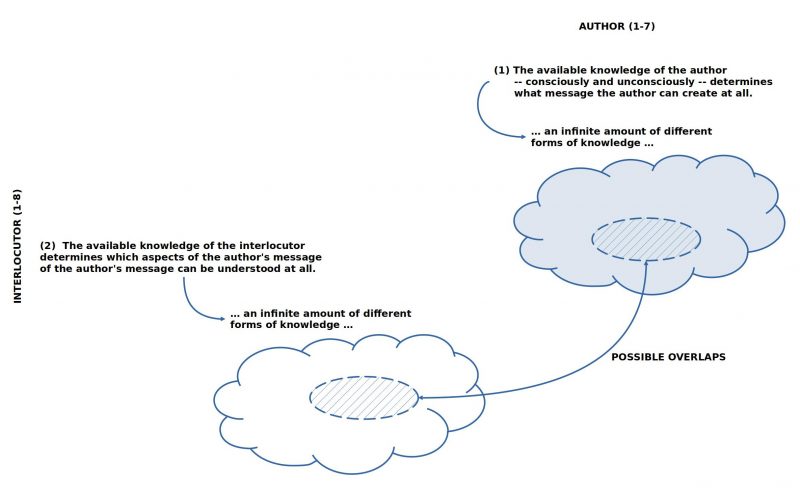

Insights on @chatGPT4 as a commentator

Let’s start with the results of the accompanying experiment with the @chatGPT4 software. If you know how the @chatGPT4 program works, you would expect the program to more or less repeat the text entered by the user and then add a few associations relative to this text, the scope and originality of which depend on the internal knowledge that the system has. As you can see from reading @chatGPT4’s comments, @chatGPT4’s commenting capabilities are clearly limited. Nevertheless they underline the main ideas quite nicely. Of course, you could elicit even more information from the system by asking additional questions, but then you would have to invest human knowledge again to enable the machine to associate more and origin of all. Without additional help, the comments remain very manageable.

Central role of narratives

As the following text suggests, narratives are of central importance both for the individual and for the collectives in which an individual occurs: the narratives in people’s heads determine how people see, experience and interpret the world and also which actions they take spontaneously or deliberately. In the case of a machine, we would say that narratives are the program that controls us humans. In principle, people do have the ability to question or even partially change the narratives they have mastered, but only very few are able to do so, as this not only requires certain skills, but usually a great deal of training in dealing with their own knowledge. Intelligence is no special protection here; in fact, it seems that it is precisely so-called intelligent people who can become the worst victims of their own narratives. This phenomenon reveals a peculiar powerlessness of knowledge before itself.

This topic calls for further analysis and more public discussion.

HERE COMES THE MAIN TEXT ABOUT NARRATIVES

Worldwide today, in the age of mass media, especially in the age of the Internet, we can see that individuals, small groups, special organizations, political groups, entire religious communities, in fact all people and their social manifestations, follow a certain ‘narrative’ [1] when they act. A typical feature of acting according to a narrative is that those who do so individually believe that it is ‘their own decision’ and that the narrative is ‘true’, and that they are therefore ‘in the right’ when they act accordingly. This ‘feeling of being in the right’ can go as far as claiming the right to kill others because they are ‘acting wrongly’ according to the ‘narrative’. We should therefore speak here of a ‘narrative truth’: Within the framework of the narrative, a picture of the world is drawn that ‘as a whole’ enables a perspective that is ‘found to be good’ by the followers of the narrative ‘as such’, as ‘making sense’. Normally, the effect of a narrative, which is experienced as ‘meaningful’, is so great that the ‘truth content’ is no longer examined in detail.[2]

Popular narratives

In recent decades, we have experienced ‘modern forms’ of narratives that do not come across as religious narratives, but which nevertheless have a very similar effect: People perceive these narratives as ‘making sense’ in a world that is becoming increasingly confusing and therefore threatening for everyone today. Individual people, the citizens, also feel ‘politically helpless’, so that – even in a ‘democracy’ – they have the feeling that they cannot directly effect anything: the ‘people up there’ do what they want after all. In such a situation, ‘simplistic narratives’ are a blessing for the maltreated soul; you hear them and have the feeling: yes, that’s how it is; that’s exactly how I ‘feel’! Such ‘popular narratives’, which make ‘good feelings’ possible, are becoming increasingly powerful. What they have in common with religious narratives is that the ‘followers’ of popular narratives no longer ask the ‘question of truth’; most are also not sufficiently ‘trained’ to be able to clarify the truth content of a narrative at all. It is typical for followers of narratives that they are generally hardly able to explain their own narrative to others. They typically send each other links to texts/videos that they find ‘good’ because these texts/videos somehow seem to support the popular narrative, and tend not to check the authors and sources because they are such ‘decent people’, because they always say exactly the same thing as the ‘popular narrative’ dictates. [3]

For Power, narratives are sexy

If one now also takes into account that the ‘world of narratives’ is an extremely tempting offer for all those who have power over people or would like to gain power over people to ‘create’ precisely such narratives or to ‘instrumentalize’ existing narratives for themselves, then one should not be surprised that many governments in this world, many other power groups, are doing just that today: they do not try to coerce people ‘directly’, but they ‘produce’ popular narratives or ‘monitor’ already existing popular narratives’ in order to gain power over the hearts and minds of more and more people via the detour of these narratives. Some speak here of ‘hybrid warfare’, others of ‘modern propaganda’, but ultimately this misses the core of the problem. [4]

Bits of history

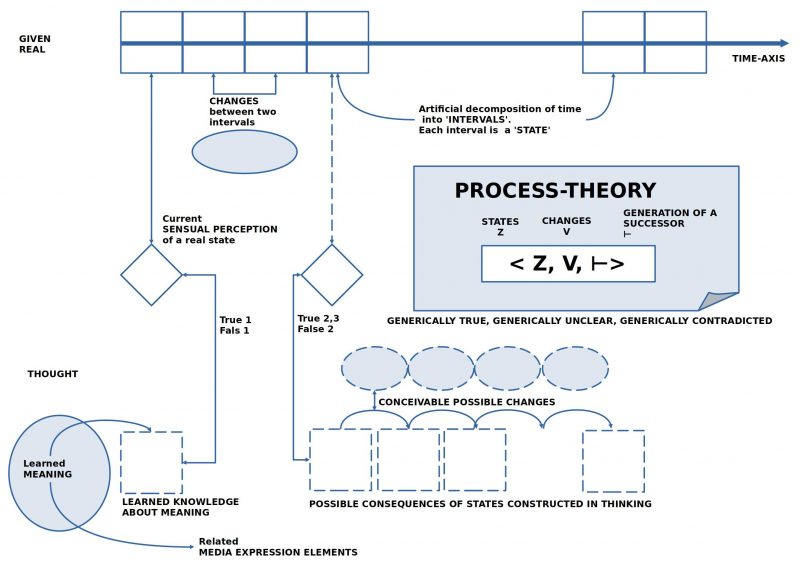

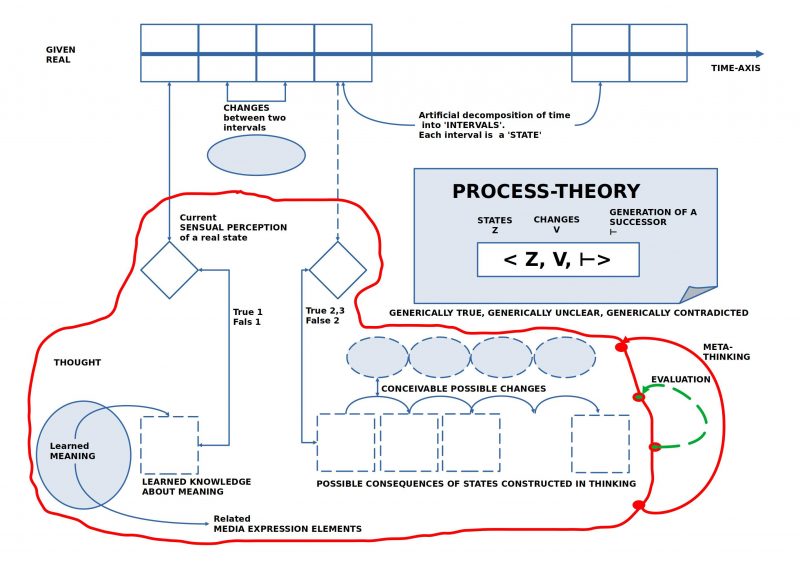

The core of the problem is the way in which human communities have always organized their collective action, namely through narratives; we humans have no other option. However, such narratives – as the considerations further down in the text show – are highly complex and extremely susceptible to ‘falsity’, to a ‘distortion of the picture of the world’. In the context of the development of legal systems, approaches have been developed to ‘improve’ the abuse of power in a society by supporting truth-preserving mechanisms. Gradually, this has certainly helped, with all the deficits that still exist today. In addition, a real revolution took place about 500 years ago: humanity succeeded in finding a format that optimized the ‘preservation of truth’ and minimized the slide into untruth with the concept of a ‘verifiable narrative (empirical theory)’. This new concept of ‘verifiable truth’ has since enabled great insights that were beyond imagination without this new concept. [5]

The ‘aura of the scientific’ has now permeated almost all of human culture, almost! We have to realize that although scientific thinking has comprehensively shaped the world of practicality through modern technologies, the way of scientific thinking has not overridden all other narratives. On the contrary, the ‘non-truth narratives’ have become so strong again that they are pushing back the ‘scientific’ in more and more areas of our world, patronizing it, forbidding it, eradicating it. The ‘irrationality’ of religious and popular narratives is stronger than ever before. ‘Irrational narratives’ are so attractive because they spare the individual from having to ‘think for himself’. Real thinking is exhausting, unpopular, annoying and hinders the dream of a simple solution.[6]

The central problem of humanity

Against this backdrop, the widespread inability of people to recognize and overcome ‘irrational narratives’ appears to be the central problem for humanity in mastering the current global challenges. Before we need more technology (we certainly do), we need more people who are able and willing to think more and better, and who are also able to solve ‘real problems’ together with others. Real problems can be recognized by the fact that they are largely ‘new’, that there exist no ‘simple off-the-shelf’ solutions for them, that we really have to ‘wrestle’ together for possible insights; the ‘old’ is not ‘enough’ in principle to recognize and implement the ‘true new’! [7]

COMMENTS

[1] The term ‘narrative’ is increasingly used today to describe the fact that a group of people use a certain ‘image’, a certain ‘narrative’ in their thinking for their perception of the world in order to be able to coordinate their joint actions. Ultimately, this applies to all collective action, even for engineers who want to develop a technical solution. In this respect, the description in the German Wikipedia is a bit ‘narrow’: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrativ_(Sozialwissenschaften)

Comments from @chatGPT4

[2] @chatGPT4 : The text delves into the profound impact of narratives in the context of mass media and the Internet, highlighting how individuals and groups often align their actions and beliefs with specific narratives. It points out the subjective nature of these narratives, where followers perceive them as absolute truths, driving their decisions and actions. This belief in the “narrative truth” can foster a strong sense of justification, even to the extent of committing violence against those deemed to be in opposition to this truth. The text emphasizes the power of narratives to shape perceptions of the world, often bypassing critical scrutiny of their factual accuracy. This phenomenon underscores the psychological and social mechanisms through which narratives influence human behavior, suggesting a collective suspension of disbelief that can have significant real-world implications.

The assertion that individuals often do not question the “truth content” of a narrative they find meaningful speaks to the cognitive biases and shortcuts humans use in processing information. Narratives simplify complex realities into coherent stories, making them more digestible and emotionally resonant. This process can lead to echo chambers and polarization, as groups coalesce around shared narratives, reinforcing their beliefs and dismissing opposing viewpoints without thorough examination.

The concept of “narrative truth” also reflects the construction of social realities, where shared beliefs and stories shape collective experiences and norms. This can have both positive and negative outcomes, facilitating social cohesion and identity within groups but also fostering division and conflict between them.

Critically, the text suggests a need for awareness and reflection on the narratives we adopt and their implications for our perceptions and actions. It hints at the ethical responsibility of individuals and media creators to critically evaluate and challenge the narratives they encounter and propagate. In an era of information overload and sophisticated digital communication, the ability to discern the nuanced difference between narrative-driven beliefs and objective truths is more crucial than ever for fostering informed, compassionate, and inclusive societies.

[3] @chatGPT4 : The text provides a critical examination of the role and influence of modern narratives in contemporary society, juxtaposing them with traditional religious narratives while highlighting their similar effects on individuals’ perceptions and emotions. It touches on a growing sense of political helplessness among citizens, even within democratic societies, where there’s a prevailing sentiment that individual actions have little to no impact on the decisions made by those in power. This perceived powerlessness, combined with the complexity and threats perceived in today’s world, creates a fertile ground for simplistic narratives to thrive. These narratives, by virtue of offering clarity and emotional comfort, gain traction and become increasingly influential.

The comparison to religious narratives is particularly insightful. It suggests that just as religious stories provide a sense of meaning, belonging, and understanding without necessitating a rigorous examination of their factual accuracy, modern narratives fulfill a similar psychological need. They offer an immediate, albeit superficial, sense of understanding and control in a seemingly chaotic world. This bypass of critical evaluation—the reluctance or inability to question the ‘truth’ behind these narratives—points to a significant challenge in contemporary discourse: the erosion of critical thinking and analytical skills in evaluating information.

Furthermore, the text highlights a concerning trend in how people consume and share information. The reliance on ‘echo chambers’ where one’s beliefs are constantly reaffirmed by similar opinions, often without scrutiny of the source’s credibility, perpetuates a cycle of misinformation and intellectual complacency. This behavior is facilitated by digital platforms, where sharing links to supportive texts or videos substitutes for genuine understanding and critical discussion.

The underlying issue, as the text implies, is not just about the narratives themselves but about the broader societal and educational failings that leave individuals unequipped to critically assess information. This deficiency not only makes people susceptible to manipulation but also undermines the foundational principles of informed citizenship in a democracy.

In conclusion, the text calls for a renewed emphasis on critical thinking and media literacy as essential skills in navigating the modern information landscape. By fostering these skills, individuals can become more discerning consumers of information, better able to understand the complexities of the world around them, and more effectively engage in the democratic process. This approach not only challenges the dominance of simplistic narratives but also supports a healthier, more informed public discourse.

[4] @chatGPT4 : This passage delves into the strategic utilization of narratives by those in power or seeking power as a means to influence and control populations. It presents a critical view of how governments and various power groups craft or harness existing popular narratives to shape public opinion and behavior indirectly. This approach, as opposed to direct coercion, operates through the subtler channels of storytelling and narrative dissemination, aiming to capture the “hearts and minds” of people. The text suggests that this method is widespread and increasingly recognized under terms like ‘hybrid warfare’ and ‘modern propaganda,’ though it argues these terms fail to fully capture the essence of the issue.

The key insight here revolves around the power of narratives to mold societal perceptions and values. By creating or modifying narratives, those in power can guide public sentiment and opinion in ways that serve their interests, often without the overt appearance of manipulation. This strategy can be particularly effective in the digital age, where information spreads rapidly and often without critical scrutiny, allowing for narratives to be amplified and tailored to target audiences with unprecedented precision.

The critique of labeling these tactics as merely ‘hybrid warfare’ or ‘modern propaganda’ highlights a deeper concern: that the focus on the mechanics of these strategies may overlook the fundamental challenge they pose to democratic processes and individual autonomy. Narratives, in this context, become tools for shaping reality, not just reflecting it, with profound implications for how people understand their world and their place within it.

Furthermore, the text implicitly raises questions about the ethical implications of such narrative control. It challenges the reader to consider the boundaries between legitimate persuasion and manipulative interference in the democratic discourse. This distinction is crucial in evaluating the health of public dialogue and the integrity of decision-making processes in a society.

In summary, the passage underscores the sophisticated ways in which narratives are employed by those in power to influence public opinion and behavior indirectly. It calls attention to the importance of recognizing and critically evaluating these narratives to preserve the principles of democracy and individual agency. The ability to discern the motivations behind and the content of these narratives is essential for a healthy, informed, and resilient public sphere.

[5] @chatGPT4 : This passage addresses a fundamental aspect of human social organization: the reliance on narratives to coordinate collective action. It posits that narratives are an intrinsic part of human nature, offering the only viable means through which communities can organize and mobilize collective action. However, it also acknowledges a critical vulnerability of narratives—their propensity for falsity and distortion of reality. This inherent flaw raises concerns about the accuracy and integrity of the stories that guide collective human behavior and decision-making.

The text suggests that the development of legal systems represents a historical attempt to mitigate the misuse of narrative power, aiming to safeguard society against the dangers of misinformation and manipulation. Legal frameworks, with their emphasis on evidence and accountability, can be seen as societal mechanisms designed to preserve truth and curb the abuse of narratives. Despite the ongoing challenges and imperfections in these systems, they have contributed to a gradual improvement in societal governance.

Moreover, the passage highlights a transformative moment in human history approximately 500 years ago with the emergence of the scientific method, described here as the concept of a “verifiable narrative (empirical theory).” This revolution in thought introduced a new paradigm for establishing truth, one based on empirical evidence and verifiability rather than mere assertion or belief. The scientific method, by demanding that claims about the world be tested and confirmed through observation and experiment, has dramatically enhanced our capacity to discern truth from falsehood. This approach has unlocked unprecedented insights and advancements, fundamentally altering humanity’s understanding of the universe and our place within it.

The core issue identified in the text is not merely the existence of narratives but the challenge of ensuring they reflect a truthful and accurate understanding of the world. The scientific method represents a pivotal development in this quest, providing a robust framework for distinguishing between verifiable truths and unfounded narratives. However, the text implies that the struggle to maintain the integrity of our collective narratives is ongoing and requires constant vigilance. As we navigate an ever-more complex information landscape, the principles of verifiability and empirical evidence remain essential guides in our pursuit of knowledge and in the organization of our societies.

[6] @chatGPT4 : This passage critically examines the influence and reach of scientific thinking in contemporary culture, juxtaposing it with the resilience and resurgence of non-scientific narratives. Despite the profound impact of scientific discoveries and technologies on practical aspects of life, the passage suggests that the mode of thinking promoted by science—characterized by critical inquiry, empirical evidence, and skepticism—has not fully supplanted other forms of narrative understanding. Instead, there is a noted resurgence of “non-truth narratives” that challenge, marginalize, or even seek to suppress scientific perspectives in various domains.

The text highlights a concerning trend: the growing appeal of irrational narratives derived from religious beliefs or popular culture, which are gaining ground against scientific rationality. This preference for irrational narratives is attributed to their simplicity and the comfort they offer individuals by absolving them of the need for critical thinking. The passage argues that real thinking—analytical, reflective, and independent—is perceived as burdensome, unpopular, and inconvenient by many, as it complicates the desire for simple answers to complex problems.

The allure of irrational narratives, according to the passage, lies in their ability to provide straightforward solutions and a sense of certainty in an increasingly complex world. These narratives offer emotional satisfaction and a framework for understanding the world that bypasses the rigorous demands of scientific scrutiny. This dynamic illustrates a broader cultural conflict between the values of rationality and the comfort of simplicity and certainty offered by alternative narratives.

This critique underscores a critical challenge facing society: the need to balance the benefits of scientific thinking with the human desire for narratives that provide meaning and emotional comfort. While scientific thinking has undeniably transformed the world, its principles of skepticism and demand for evidence can be at odds with the human inclination towards narratives that offer immediate clarity and solace. The passage calls for a reflection on the importance of fostering a culture that values critical thinking and scientific literacy while acknowledging and addressing the psychological and emotional needs that drive people towards irrational narratives. This balance is crucial for navigating the complexities of the modern world and ensuring that decisions are informed by both empirical evidence and a compassionate understanding of human nature.

[7] @chatGPT4 : This passage articulates a critical observation about contemporary society’s struggle with global challenges: the difficulty lies not just in the need for technological advancements but fundamentally in the widespread inability of individuals to engage critically with information and narratives. It underscores the necessity of fostering a culture where people are encouraged and equipped to think deeply, critically, and collaboratively to address complex issues. The emphasis is on the collective intellectual effort required to navigate and solve “real problems,” which are characterized as novel, lacking straightforward solutions, and demanding innovative approaches beyond the application of existing knowledge or methods.

The text suggests that the crux of addressing global challenges effectively is not merely technological innovation but, more importantly, enhancing collective cognitive capabilities. It highlights an urgent need for individuals who can think “more and better” and who are prepared to engage in the collaborative problem-solving processes essential for addressing the unique and multifaceted problems facing the world today. These problems are not amenable to simple, pre-packaged solutions; they require a willingness to engage in sustained intellectual effort, open-minded exploration, and creative thinking.

This perspective challenges the prevailing emphasis on technological solutions as the primary means to overcome global challenges. Instead, it argues for a paradigm shift towards valuing and developing human intellectual and collaborative capacities as the foundational step towards sustainable progress. The passage points out that the real bottleneck in addressing contemporary issues is not the lack of technological resources but the shortage of people capable of employing critical thinking to innovate and implement effective solutions.

In essence, the passage calls for a renewed focus on education and cultural values that promote critical thinking, intellectual curiosity, and collaborative problem-solving. By cultivating these capabilities, society can better equip itself to recognize, understand, and address the novel and complex challenges that define our times. This approach not only recognizes the limitations of relying solely on technological advancements but also highlights the transformative potential of human intellect and cooperation in forging pathways to a better future.