eJournal: uffmm.org

ISSN 2567-6458, 28.February 2023 – 28.February 2023, 10:45 CET

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

Parts of this text have been translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version), afterwards only minimally edited.

— Not yet finished —

CONTEXT

This post is part of the book project ‘oksimo.R Editor and Simulator for Theories’.

Abstract Elements

The abstract elements introduced so far are still few, but they already allow to delineate a certain ‘abstract space’. Thus there are so far

- Abstract elements in current memory (also ‘consciousness’) based on concrete perception,

- which then can pass over into stored abstract – and dynamic – elements of potential memory,

- further abstract concepts of n.th order in current as well as in potential memory,

- Abstract elements in current memory (also ‘consciousness’) based on concrete perception, which function as linguistic elements,

- which can then also pass over into stored abstract – and dynamic – elements of potential (linguistic) memory,

- likewise abstract linguistic concepts of nth order in actual as well as in potential memory,

- abstract relations between abstract linguistic elements and abstract other elements of current as well as potential memory (‘meaning relations’).

- linguistic expressions for the description of factual changes and

- linguistic expressions for the description of analytic changes.

The generation of abstract linguistic elements thus allows in many ways the description of changes of something given, which (i) is either only ‘described’ as an ‘unconditional’ event or (ii) works with ‘rules of change’, which clearly distinguishes between ‘condition’ and ‘effect’. This second case with change-rules can be related to many varieties of ‘logical inference’. In fact, any known form of ‘logic’ can be ’emulated’ with this general concept of change rules.

This idea, only hinted at here, will be explored in some detail and demonstrated in various applications as we proceed.

Glimpses of an Ontology

Already these few considerations about ‘abstract elements’ show that there are different forms of ‘being’.[1].

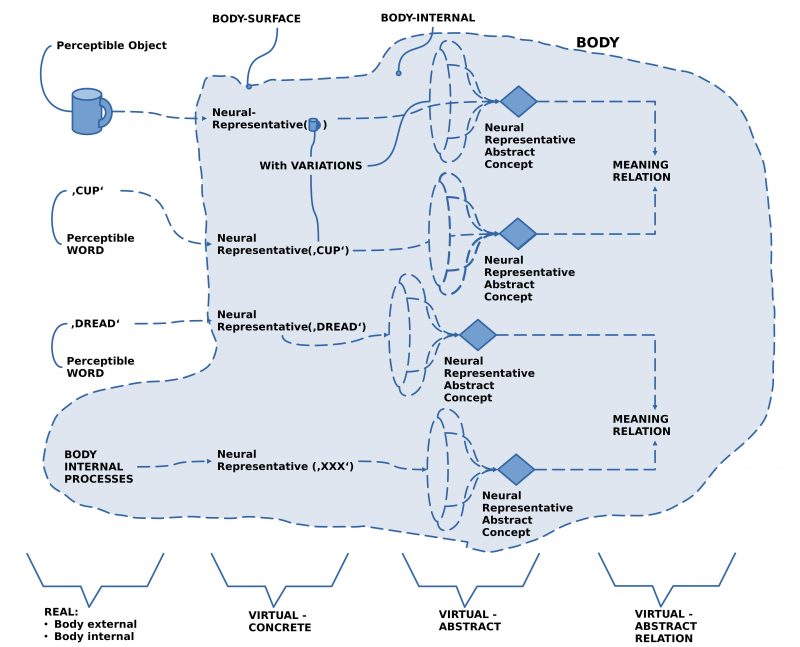

In the scheme of FIG. 1, there are those givens in the real external world which can become the trigger of perceptions. However, our brain cannot directly recognize these ‘real givens’, only their ‘effects in the nervous system’: first (i) as ‘perceptual event’, then (ii) as ‘memory construct’ distinguished into (ii.1) ‘current memory (working memory, short-term memory, …) and (ii.2) ‘potential memory’ (long-term memory, various functional classifications, …).”[2]

If one calls the ‘contents’ of perception and current memory ‘conscious’ [3], then the primary form of ‘being’, which we can directly get hold of, would be those ‘conscious contents’, which our brain ‘presents’ to us from all its neuronal calculations. Our ‘current perceptions’ then stand for the ‘reality out there’, although we actually cannot grasp ‘the reality out there’ ‘directly, immediately’, but only ‘mediated, indirectly’.

Insofar as we are ‘aware’ of ‘current contents’ that ‘potential memory’ makes ‘available’ to us (usually called ‘remembering’ in everyday life; as a result, a ‘memory’), we also have some form of ‘primary being’ available, but this primary being need not have any current perceptual counterpart; hence we classify it as ‘only remembered’ or ‘only thought’ or ‘abstract’ without ‘concrete’ perceptual reference.

For the question of the correspondence in content between ‘real givenness’ and ‘perceived givenness’ as well as between ‘perceived givenness’ and ‘remembered givenness’ there are countless findings, all of which indicate that these two relations are not ‘1-to-1’ mappings under the aspect of ‘mapping similarity’. This is due to multiple reasons.

In the case of the perceptual similarity with the triggering real givens, already the interaction between real givens and the respective sense organs plays a role, then the processing of the primary sense data by the sense organ itself as well as by the following processing in the nervous system. The brain works with ‘time slices’, with ‘selection/condensation’ and with ‘interpretation’. The latter results from the ‘echo’ from potential memory that ‘comments’ on current neural events. In addition, different ’emotions’ can influence the perceptual process. [4] The ‘final’ product of transmission, processing, selection, interpretation and emotions is then what we call ‘perceptual content’.

In the case of ‘memory similarity’ the processing of ‘abstracting’ and ‘storing’, the continuous ‘activations’ of memory contents as well as the ‘interactions’ between remembered things indicate that ‘memory contents’ can change significantly in the course of time without the respective person, who is currently remembering, being able to read this from the memory contents themselves. In order to be able to recognize these changes, one needs ‘records’ of preceding points in time (photos, films, protocols, …), which can provide clues to the real circumstances with which one can compare one’s memories.”[5]

As one can see from these considerations, the question of ‘being’ is not a trivial question. Single fragments of perceptions or memories tend to be no 1-to-1 ‘representatives’ of possible real conditions. In addition, there is the high ‘rate of change’ of the real world, not least also by the activities of humans themselves.

COMMENTS

[1] The word ‘being’ is one of the oldest and most popular concepts in philosophy. In the case of European philosophy, the concept of ‘being’ appears in the context of classical Greek philosophy, and spreads through the centuries and millennia throughout Europe and then in those cultures that had/have an exchange of ideas with the European culture. The systematic occupation with the concept ‘being’ the philosophers called and call ‘ontology’. See for this the article ‘Ontology’ in wkp-en: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology .

[2] On the subject of ‘perception’ and ‘memory’ there is a huge literature in various empirical disciplines. The most important may well be ‘biology’, ‘experimental pschology’ and ‘brain science’; these supplemented by philosophical ‘phenomenology’, and then combinations of these such as ‘neuro-psychology’ or ‘neuro-phenomenology’, etc. In addition there are countless other special disciplines such as ‘linguistics’ and ‘neuro-linguistics’.

[3] A question that remains open is how the concept of ‘consciousness’, which is common in everyday life, is to be placed in this context. Like the concept of ‘being’, the concept of ‘consciousness’ has been and still is very prominent in recent European philosophy, but it has also received strong attention in many empirical disciplines; especially in the field of tension between philosophical phenomenology, psychology and brain research, there is a long and intense debate about what is to be understood by ‘consciousness’. Currently (2023) there is no clear, universally accepted outcome of these discussions. Of the many available working hypotheses, the author of this text considers the connection to the empirical models of ‘current memory’ in close connection with the models of ‘perception’ to be the most comprehensible so far. In this context also the concept of the ‘unconscious’ would be easy to explain. For an overview see the entry ‘consciousness’ in wkp-en: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consciousness

[4] In everyday life we constantly experience that different people perceive the same real events differently, depending on which ‘mood’ they are in, which current needs they have at the moment, which ‘previous knowledge’ they have, and what their real position to the real situation is, to name just a few factors that can play a role.

[5] Classical examples for the lack of quality of memories have always been ‘testimonies’ to certain events. Testimonies almost never agree ‘1-to-1′, at best ‘structurally’, and even in this there can be ‘deviations’ of varying strength.