eJournal: uffmm.org

ISSN 2567-6458, 27.February 2023 – 27.February 2023, 01:45 CET

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

Parts of this text have been translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version), afterwards only minimally edited.

CONTEXT

( This text is an direct continuation of the text “The ‘inside’ of the ‘outside’. Basic Building Blocks”) within the project ‘oksimo.R Editor and Simulator for Theories’.

‘Transient’ events and language

After we have worked our way forward in the biological cell galaxy ‘man’ so far that we can determine its ‘structuredness’ (without really understanding its origin and exact functioning), and then find ourselves according to the appearance as ‘concrete body’ which can ‘communicate’ with the ‘environment of the own body’ (often also called ‘outside world’) twofold: We can ‘perceive’ in different ways and we can produce ‘effects’ in the outside world in different ways.

For the ‘coordination’ with other human bodies, especially between the ‘brains’ in these bodies, the ability to ‘speak-listen’ or then also to ‘write-read’ seems to be of highest importance. Already as children we find ourselves in environments where language occurs, and we ‘learn’ very quickly that ‘linguistic expressions’ can refer not only to ‘objects’ and their ‘properties’, but also to fleeting ‘actions’ (‘Peter gets up from the table’) and also other ‘fleeting’ events (‘the sun rises’; ‘the traffic light just turned red’). There are also linguistic expressions that refer only partially to something perceptible, such as ‘Hans’ father’ (who is not in the room at all), ‘yesterday’s food’ (which is not there), ‘I hate you’ (‘hate’ is not an object), ‘the sum of 3+5’ (without there being anything that looks like ‘3’ or ‘5’), and many more.

For the ‘coordination’ with other human bodies, especially between the ‘brains’ in these bodies, the ability to ‘speak-listen’ or then also to ‘write-read’ seems to be of highest importance. Already as children we find ourselves in environments where language occurs, and we ‘learn’ very quickly that ‘linguistic expressions’ can refer not only to ‘objects’ and their ‘properties’, but also to fleeting ‘actions’ (‘Peter gets up from the table’) and also other ‘fleeting’ events (‘the sun rises’; ‘the traffic light just turned red’). There are also linguistic expressions that refer only partially to something perceptible, such as ‘The father of Bill’ (who is not in the room at all), ‘yesterday’s food’ (which is not there), ‘I hate you’ (‘hate’ is not an object), ‘the sum of 3+5’ (without there being anything that looks like ‘3’ or ‘5’), and many more.

If one tries to understand these ‘phenomena of our everyday life’ ‘more’, one can come across many exciting facts, which possibly generate more questions than they provide answers. All phenomena, which can cause ‘questions’, actually serve the ‘liberation of our thinking’ from currently wrong images. Nevertheless, questions are not very popular; they disturb, stress, …

How can one get closer to these manifold phenomena?

Let’s just look at some expressions of ‘normal language’ that we use in our ‘everyday life’.[1] In everyday life there are many different situations in which we sit down (breakfast, office, restaurant, school, university, reception hall, bus, subway, …). In some of these situations we speak, for example, of ‘chairs’, in others of ‘armchairs’, again in other situations of ‘benches’, or simply of ‘seats’. Before an event, someone might ask “Are there enough chairs?” or “Do we have enough armchairs?” or … In the respective concrete situation, it can be quite different objects that would pass for example as ‘chair’ or as ‘armchair’ or … This indicates that the ‘expressions of language’ (the ‘sounds’, the ‘written/printed signs’) can link to quite different things. There is no 1-to-1 mapping here. With other objects like ‘cups’, ‘glasses’, ‘tables’, ‘bottles’, ‘plates’ etc. it is not different.

These examples suggest that there seems to be a ‘structure’ here that ‘manifests’ itself in the concrete examples, but is itself located ‘beyond the events.'[2].

If one tries to ‘mentally sort’ this out, then at least two, rather three ‘dimensions’ suggest themselves here, which play into each other:

- There are concrete linguistic expressions – those we call ‘words’ – that a ‘speaker-hearer’ uses.

- There is, independently of the linguistic expressions, ‘some phenomenon’ in everyday life to which the ‘speaker-hearer’ refers with his linguistic expression (these can be ‘objects’ or ‘properties’ of objects, …)[3].

- The respective ‘speaker’ or ‘listener’ has ‘learned’ to establish a ‘relation’ between the ‘linguistic expression’ and the ‘other to the linguistic expression’.

Since we know that the same objects and events in everyday life can be ‘named’ quite differently in the ‘different languages’, this suggests that the relations assumed in each case by ‘speaker-hearer’ are not ‘innate’, but appear rather ‘arbitrary’ in each ‘language community’.[4] This suggests that the ‘relations’ found in everyday life between linguistic expressions and everyday facts have to be ‘learned’ by each speaker-hearer individually, and this through direct contact with speaker-hearers of the respective language community.

Body-External Conditions

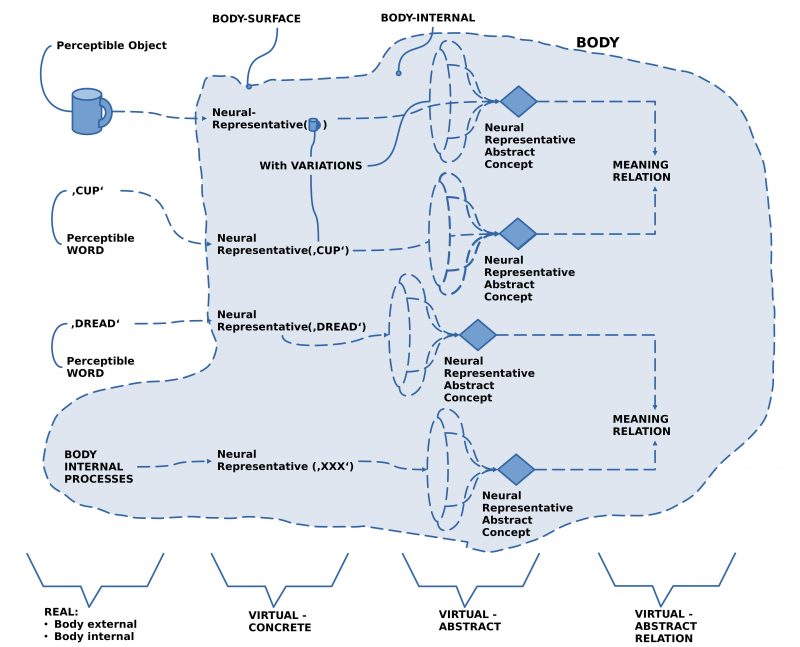

The previous considerations allow the formation of a ‘working hypothesis’ for the phenomenon that a speaker-hearer can encounter ‘outside his body’ single objects (e.g. an object ‘cup’, a word ‘cup’), which as such have no direct relation to each other. But inside the speaker-hearer, ‘abstract concepts’ can then be formed triggered by the perceived concrete events, which ‘abstract a common core’ from the varying occurrences, which then represents the actual ‘abstract concept’.

Under the condition of such abstract concepts, ‘meaning relations’ can then form in the speaker-listener in such a way that a speaker can ‘learn’ to ‘mentally link’ the two individual objects ‘cup’ (as an object) and ‘cup’ (as a heard/written word) in such a way, that in the future the word ‘cup’ evokes an association with the object ‘cup’ and vice versa. This relationship of meaning (object ‘cup’, word ‘cup’) is based on ‘neural processes’ of perception and memory. They can form, but do not have to. If such neural processes are available, then the speaker-hearer can actualize the cognitive element ‘object cup’ even if there is no outside object available; in this case there is no ‘perceptual element’ available too which ‘corresponds’ to the ‘memory element’ object cup.

Given these assumptions, one can formulate two more assumptions:

(i) Abstraction from abstract concepts: the mechanism of ‘abstract concept formation’ works not only under the condition of concrete perceptual events, but also under the condition of already existing abstract concepts. If I already have abstract concepts like ‘table’, ‘chair’, ‘couch’, then I can, for example, form an abstract concept ‘furniture’ as an ‘umbrella concept’ to the three previously mentioned concepts. If one calls abstract concepts that directly refer to virtual-concrete concepts level 1 concepts, then one could call abstract concepts that presuppose at least one concept of level n level n+1 concepts. How many levels are of ‘use’ in the domain of abstract concepts is open. In general, the ‘higher the level’, the more difficult it is to tie back to level-0 concepts.

(ii) Abstraction forming meaning concepts: : the ‘mechanism of forming meaning relations’ also works with reference to arbitrary abstract concepts.

If Hans says to Anna, “Our furniture seems kind of worn out by now,” then the internal relation Furniture := { ‘table’, ‘chair’, ‘couch’ } would lead from the concept Furniture to the other subordinate concepts, and Anna would know (given the same language understanding) that Hans is actually saying, “Our furniture in the form of ‘table’, ‘chair’, ‘couch’ seems kind of worn out by now.”

Body internal Conditions

From the view of the brain are ‘body-internal processes’ (different body organs, manifold ‘sensors’, and more) also ‘external’ (see figure)! The brain also knows about these body-internal conditions only insofar as corresponding ‘signals’ are transmitted to it. These can be assigned to different ‘abstract concepts’ by the memory due to their ‘individual property profile’, and thus they also become ‘candidates for a semantic relation’. However, only if these abstractions are based on body-internal signal events that are represented in ‘current memory’ in such a way that ‘we’ become ‘aware’ of them. [5],[6]

The ‘body-internal event space’ that becomes ‘noticeable’ in the current memory is composed of very many different events. Besides ‘organ-specific’ signals, which sometimes can even be ‘localized’ to some extent inside the body (‘my left molar hurts’, ‘my throat itches’, ‘I am hungry’, etc.). ), there are very many ‘moods’/’feelings’/’emotions’ which are difficult or impossible to localize, but which are nevertheless ‘conscious’, and to which one can assign different ‘intensities’ (‘I am very sad’, ‘This makes me angry’, ‘The situation is hopeless’, ‘I love you very much’, ‘I don’t believe you’, …).

If one ‘assigns words’ to such ‘body-internal’ properties, then also a ‘meaning relation’ arises, however it is then differently difficult to almost unsolvable between two human actors to clarify in each case ‘for oneself’, what ‘the other’ probably ‘means’, if he uses a certain linguistic expression. In the case of ‘localizable’ linguistic expressions, one may be able to understand what is meant because of a similar physical structure (‘my left molar hurts’, ‘my throat itches’, ‘I am hungry’). With other, non-localizable linguistic expressions (‘I am very sad’, ‘This makes me angry’, ‘The situation is hopeless’, ‘I love you very much’, ‘I don’t believe you’, …) it becomes difficult. Often one can only ‘guess’; wrong interpretations are very likely.

It becomes exciting when speaker-hearers combine in their linguistic expressions not only such concepts that derive from body-external perceptual events, but also such concepts that derive from body-internal perceptual events. For example, when someone says “That red car over there, I don’t have a good feeling about it” or “Those people there with their caps scare me” or “When I see that fish roll, it really gives me an appetite” or “Oh, that great air,” etc. We make statements like these all the time. They manifest a continuous ‘duality of our world experience’: with our body we are ‘in’ an external body world, which we can specifically perceive, and at the same time we fragmentarily experience the ‘inside of our body’, how it reacts in the current situation. We can also think of it this way: Our body talks to us by means of the ‘body-internal signals’ about how it experiences/feels/ senses a current ‘external situation’.

Spatial Structures

In the figure above the perceptions and the current memories are represented ‘individually’. But in fact the brain processes all signals of the ‘same time slice’ [7] as if they were ‘elements of a three-dimensional space’. As a consequence, there are ‘spatial relations’ between the elements without the elements themselves being able to generate such relations. In the case of body-external percepts, there is a clear ‘beside’, ‘in front of’, ‘under’, etc. In the case of body-internal perceptions, the body forms a reference point, but the body as a reference point is differently concrete (‘My left toe…’, ‘I am tired’, ‘My stomach growls’, …).

If the speaker-hearers use ‘measuring operations’ in addition to their ‘normal’ innate perception in the case of body-external circumstances, then one can assign different measured values to the ‘circumstances in space’ (lengths, volumes, position in a coordinate system, etc.).

In the case of ‘body-internal’ conditions one can ‘measure’ the body itself including process properties – what e.g. experimental psychologists and brain researchers often do -, but the connection with the body-internal perceptions is, depending on the kind of the ‘body-internal perception’, either only ‘to some extent’ producible (‘My left tooth hurts’), or ‘rather not’ (‘I feel so weak today’, ‘Just now this thought popped into my head’).

Time: Now, Before, ‘Possible’

From everyday life we know the phenomenon that we can perceive ‘changes’: ‘The traffic light turns red’, ‘The engine starts’, ‘The sun rises’, … This is so natural to us that we hardly think about it.

This concept of ‘change’ presupposes a ‘now’ and a ‘before’ and the ability to ‘recognize differences’ between the ‘now’ and the ‘before’.

As a working hypothesis [9] for this property of recognizing ‘change’, the following assumptions are made here:

- Events as part of spatial arrangements are deposited as ‘situations’ in ‘potential memory’ in such a way that ‘current perceptions’ that differ from ‘deposited (before)’ situations are ‘noticed’ by unconscious comparison operations: we notice, without wanting to, that the traffic light changes from orange to green. We can describe such ‘changes’ by juxtaposing the ‘before’ and ‘now’ states.

- In a ‘comparison’ in the context of ‘changes’ we use ‘abstract remembered’ concepts in conjunction with ‘abstract perceived’ concepts, e.g. the state of the traffic light ‘before’ and ‘now’.

- ‘Current’ perceptions quickly pass into ‘remembered’ perceptions (The transition of the traffic light from orange to green happened ‘just’).

- We can ‘arrange’ the abstract concepts of remembered percepts ‘in a sequence/row’ such that an element in the row can be seen as ‘temporally’ prior’ to a subsequent element, or ‘temporally posterior’. By mapping into ‘linguistic expressions’ one can make these facts ‘more explicit’.

- By the availability of ‘temporal relations’ (‘x is temporally before y’, ‘y is temporally after x’, ‘y is temporally simultaneous with y’, …) one gains a starting point for considering ‘frequencies’ in these relations, e.g. “Is y temporally ‘always’ after y” or only ‘sometimes’? Is this temporal pattern ‘random’ or somehow ‘significant’?

- If the observed ‘patterns of temporal occurrence’ are ‘not purely random’ but imply significant probabilities, then on this basis one can formulate ‘hypotheses for such situations’ which ‘are not past and not present’, but in the light of the probabilities appear as ‘possible in the future’.

Time: factual and analytical

The preceding considerations about time assume that the ‘recognition of changes’ is based on an ‘automatic perception’: that something ‘changes’ in our perceptual space is based on ‘unconscious neuronal processes’ which ‘automatically detect’ this change and ‘automatically bring it to our attention’ without us having to do this ‘consciously’. In all languages there are linguistic expressions reflecting this: ‘drive’, ‘change’, ‘grow’, ‘fly’, ‘melt’, ‘heat’, ‘age’, … We can take notice of changes with a certain ‘ease’, but nothing more. It is the ‘pure fact’ of change what makes itself noticeable to us; hence the phrase ‘factual time’.

If we want to ‘understand’ what exactly happens during a change, why, under which conditions, how often, in which period of time etc., then we have to make the effort to ‘analyze’ such changes in more detail. This means we have to look at the ‘whole process of change’ and try to identify as many ‘individual moments’ in it that we can then – eventually – find clues as to what exactly happened, how and why.

Such an analysis can only succeed if we can answer the following questions:

- How to describe the situation ‘before’ the change?

- How can one describe the situation ‘after’ the change?

- What exactly are the ‘differences’?

- How can one formulate an if-then rule that states at which ‘condition’ which ‘change’ should be applied in such a way that the desired ‘new state’ results with all ‘changes’?

Example: A passer-by observes that a traffic light changes from orange to green. A (simple) analysis could work as follows:

change Rule (simple format)

- Before: The traffic light is orange.

- After: The traffic light is green.

- Difference: The ‘orange’ property has been replaced by the ‘green’ property.

Rule as a ‘text’:

Change rule: If: ‘A traffic light is orange’. Then: (i) Remove ‘A traffic light is orange’, (ii) Add: ‘A traffic light is green’.

If one wants to deepen this thought, one quickly encounters many questions concerning a single rule of change:

- What is important about a ‘situation before’? Is it necessary to write down ‘everything’ or only ‘partial aspects’? How does a group of human actors determine the ‘boundary’ from the situation to the wider environment? If only a partial description: how does one determine what is important?

- Corresponding questions also arise for the description of the ‘situation after’.

- It is also exciting to ask about the ‘if-part’ of the change rule: how many of the facts of the situation before are important? Are all of them important or only some? For example, if I can distinguish three facts: do they all have to be fulfilled ‘simultaneously’ or only ‘alternatively’?

- Interesting is also the ‘relation’ between the situation before and after: Is this observable change (i) ‘completely random’ or (ii) does this relation have a ‘certain frequency’ (a certain ‘probability value’), or (iii) does this relation ‘always’ occur?

If one looks at concrete examples of normal language usage on ‘factual time’ with these questions in mind, one can easily see how ‘minimalist’ change is practiced linguistically in everyday life:

- Peter goes upstairs.

- Are you coming?

- He finished the glass.

- She opened the door.

- We ate in silence.

- …

All of these expressions (1) – (5) only briefly address the nature of the change, hint at the persons and objects involved, and leave the space in which this occurs unmentioned. The exact duration is also not explicitly stated. The speaker-listeners in these situations obviously presuppose that everyone can ‘infer the corresponding meaning for himself’ on the basis of the linguistic utterances on the one hand through ‘general linguistic knowledge’, on the other hand through being ‘concretely involved’ in the respective concrete situation.

A completely different aspect is provided in the case of an ‘analytic time’ by the question of the ‘description itself’, the ‘rule text’:

Change rule: If: ‘A traffic light is orange’. Then: (i) Remove ‘A traffic light is orange’, (ii) Add: ‘A traffic light is green’.

This text contains linguistic expressions ‘A traffic light is orange’ as well as ‘A traffic light is green’. These linguistic expressions have in the normal language mostly a certain ‘linguistic meaning’, which refer in this case to ‘memories’, which were formed due to ‘perceptions’. It is about the abstract object ‘traffic light’, to which the abstract properties ‘orange’ or ‘green’ are attributed or denied. Normally, speaker-hearers of English have learned to relate these abstract meanings on the occasion of a ‘concrete perception’ to such concrete realities (real traffic lights) which they have learned to ‘belong’ to in the course of their language learning. Without a current concrete perception, it is only a matter of abstract meanings by means of abstract memories, whose ‘reference to reality’ is only ‘potential’. Only with the occurrence of a concrete perception with the ‘suitable properties’ the ‘potential’ meaning becomes a ‘real given’ (empirical) meaning.

The text of a change rule thus abstractly describes a possible transition from an abstractly described situation to an abstractly possible other situation. Whether this abstract possibility ever becomes a concrete real meaning is open. The condensation of ‘repeated events’ of the same kind in the past (stored as memory) in the concept of ‘frequency’ or then in the concept of a ‘probability’ can indeed influence the ‘expectation of an actor’ to the effect that he ‘takes into account’ in his behavior that the change can occur if he ‘recreates’ the ‘triggering situation’, but there would be complete certainty of this only if the described change were based on a completely deterministic context.

What does not appear in this simple consideration is the temporal aspect: whether a change takes place in the millisecond range or in hours, days, months, years, that marks enormous differences.

Likewise the reference to a space: Where does it take place? How?

Working hypothesis CONTEXT

Linguistic descriptions of change happen as ‘abstract formulations’ and usually assume the following:

- A shared linguistic knowledge of meaning in the minds of those involved.

- A knowledge of the spatial situation in which the change takes place.

- A knowledge of the people and objects involved.

- A knowledge of the temporal dimension.

- Optional: a knowledge of experiential probability.

Descriptions of change, which are written abstractly, must – depending on the case and requirement – make the context aspects (1) – (5) explicit, in order to be ‘understandable’.

The demand for ‘comprehensibility’ is, however, in principle ‘vague’, since the respective contexts can be arbitrarily complex and arbitrarily different.

COMMENTS

[1] Instead of ‘normal language’ in ‘everyday life’ I also simply speak of ‘everyday language’ here.

[2] A thinker who has dealt with this phenomenon of the ‘everyday concrete’ and at the same time also ‘everyday – somehow – abstract’ is Ludwig Wittgenstein (see [2b,c]). He introduced the concept of ‘language-game’ for this purpose, without introducing an actual ‘(empirical) theory’ in the proper sense to comprise all these considerations.

[2b] Wittgenstein, L.; Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1921/1922 /* Written during World War I, the work was completed in 1918. It first appeared with the support of Bertrand Russell in Wilhelm Ostwald’s Annalen der Naturphilosophie in 1921. This version, which was not proofread by Wittgenstein, contained gross errors. A corrected, bilingual edition (German/English) was published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. in London in 1922 and is considered the official version. The English translation was by C. K. Ogden and Frank Ramsey. See introductory Wikipedia-EN: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus .

[2c] Wittgenstein, L.; Philosophical Investigations (Original Title: Philosophische Untersuchungen),1936-1946, published 1953 . Remark: ‘The Philosophical Investigations’ is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s late, second major work. It exerted an extraordinary influence on the philosophy of the 2nd half of the 20th century; the speech act theory of Austin and Searle as well as the Erlangen constructivism (Paul Lorenzen, Kuno Lorenz) are to be mentioned. The book is directed against the ideal of a logic-oriented language, which, along with Russell, Carnap, and Wittgenstein himself had advocated in his first major work. The book was written in the years 1936-1946, but was not published until 1953, after the author’s death. See introductory Wikipedia-EN: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophical_Investigations .

[3]In the borderline case, these ‘other’ phenomena of everyday life are also linguistic expressions (when one talks ‘about’ a text or linguistic utterances’).

[4] See: Language Family in wkp-en: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_family Note: Due to ‘spatial proximity’ or temporal context (or both), there may be varying degrees of similarity between different languages.

[5] On the subject of ‘perception’ and ‘memory’ there is a huge literature in various empirical disciplines. The most important ones may well be ‘biology’, ‘experimental psychology’ and ‘brain science’; these supplemented by philosophical ‘phenomenology’, and then combinations of these such as ‘neuro-psychology’ or ‘neuro-phenomenology’, etc. In addition, there are countless other special disciplines such as ‘linguistics’ and ‘neuro-linguistics’.

[6] A question that remains open is how the concept of ‘consciousness’, which is common in everyday life, is to be placed in this context. Like the concept of ‘being’, the concept of ‘consciousness’ has been and still is very prominent in recent European philosophy, but it has also received strong attention in many empirical disciplines; especially in the field of tension between philosophical phenomenology, psychology and brain research, there is a long and intense debate about what is to be understood by ‘consciousness’. Currently (2023) there is no clear, universally accepted outcome of these discussions. Of the many available working hypotheses, the author of this text considers the connection to the empirical models of ‘current memory’ in close connection with the models of ‘perception’ to be the most comprehensible so far. In this context also the concept of the ‘unconscious’ would be easy to explain. For an overview see the entry ‘consciousness’ in wkp-en: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consciousness

[7] The findings about ‘time slices’ in the processing of body-external circumstances can be found in many works of experimental psychology and brain research. A particularly striking example of how this factor plays out in human behavior is provided by the book by Card, Moran, and Newell (1983), see [8].

[8] Stuart K.Card, Thomas P.Moran, Allen Newell, (1983),The Psychology of Human-Computer Interaction, CRC-Press (Taylor & Francis Group), Boca Raton – London – New York. Note: From the point of view of the author of this text, this book was a milestone in the development of the discipline of human-machine interaction.

[9] On the question of memory, especially on the question of the mechanisms responsible for the storage of contents and their further processing (e.g. also ‘comparisons’), there is much literature, but no final clarity yet. Here again the way of a ‘hypothetical structure formation’ is chosen: explicit assumption of a structure that ‘somewhat explains’ the available phenomena with openness for further modifications.